by Carolyn Phenicie

Education advocates of all stripes, from the most ardent reformers to the staunchest union leaders, are fond of saying education is the civil rights issue of our time. Presidents like it too: George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump have all used the phrase.

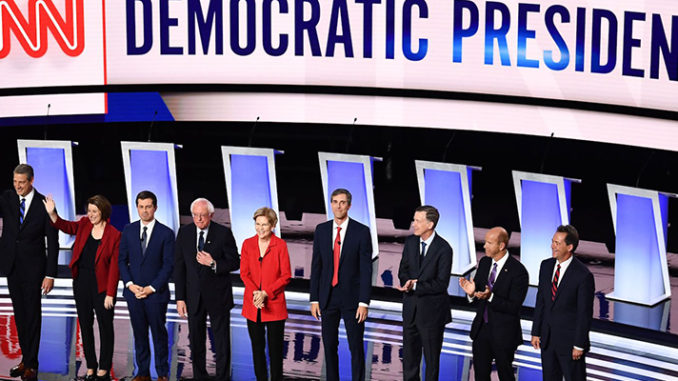

In keeping with that tradition, Democrats in their second set of debates Tuesday and Wednesday also made that link — one that makes sense in a country where since 2015, the majority of public school students have been non-white.

There were some glancing references to the issue on the first night of the debates, in response to questions about reparations for slavery or who is the best candidate to heal the country’s racial divide. Sen. Bernie Sanders touted his proposal to triple Title I funding, for instance, and former Colorado governor John Hickenlooper talked up his efforts to expand pre-K when he was mayor of Denver.

But discussion of education as a remedy for racial division really came into its own on the debate’s second evening.

Moderators raised the issue Wednesday as a follow-up to the dust-up between former vice president Joe Biden and Sen. Kamala Harris last month over Biden’s opposition to busing students to integrate schools, something Harris had experienced as a child.

After they disputed their relative positions, and Biden accused Harris of failing to act to desegregate schools in San Francisco and Los Angeles, moderators asked Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet why he’s the best candidate to heal the country’s racial divide.

Bennet, formerly Denver superintendent, instead tried to steer the conversation to current concerns.

“This is the fourth debate that we have had, and the second time that we have been debating what people did 50 years ago with busing, when our schools are as segregated today as they were 50 years ago. We need a conversation about what’s happening now,” he said.

When some children get the chance to go to preschool and some do not, or when schools don’t receive equitable resources, “equal is not equal,” he added.

“I believe you can draw a straight line from slavery through Jim Crow through the banking and the redlining to the mass incarceration that we were talking about on this stage a few minutes ago. But you know what other line I can draw? Eighty-eight percent of the people in our prisons dropped out of high school. Let’s fix our school system and maybe we can fix the prison pipeline that we have,” he said.

(Fact-checkers have questioned the 88 percent figure, which was 30 percent in a 2014 study. Other sources, using older data, found that 75 percent of state prison inmates and 59 percent of federal inmates had dropped out.)

Other candidates, too, referenced their records on and plans for education, though few to Bennet’s extent. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, for instance, referred to reducing the school-to-prison pipeline.

And when former housing and urban development secretary Julián Castro was asked about what he’d do for Baltimore, newly the target of Trump’s ire, he also linked to schools. Castro mentioned “tremendous educational opportunity,” such as universal pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds and new K-12 dollars, along with investments in affordable housing.

The one specific education issue that received significant airtime in this round of debates was free college and higher ed affordability; candidates on the first night discussed their proposals, and specifically how much they should cover and whether their programs should be universal or targeted to the neediest students.

Carolyn Phenicie is a senior writer and DC correspondent for The 74 based in Washington, D.C., covering Congress, the Education Department, and the White House.