by Conor Williams

Video games are bad for you; they’re distracting,” says one kid. “They’re too violent,” says another. It’s jarring to hear middle-schoolers talk down on-screen entertainment, but the boys in this Bay Area classroom are doing their level best — and in Spanish, no less.

To be sure, they’re practicing taking positions and marshaling evidence as part of a unit on persuasive essay writing. “Are you guys serious about this?” I ask. “Oh yes, sir, we’re good kids,” says one — and he winks.

Sixth-grade eye twinkles aside, he’s right. English learner students here at Voices College-Bound Language Academies significantly outperform their peers across the state in reading and math. The same is true for the dual-language immersion school’s Hispanic students and students from low-income families. Whether or not those guys still play FIFA 20 on the sly, it’s clear that Voices runs an excellent network of schools.

As charter schools, Voices use their public funding — and flexibility on staffing, curricula and scheduling — to provide academic instruction in Spanish and English. This helps them tailor their school model for their students, nearly three-quarters of whom come from low-income families. In addition, 92 percent are Hispanic and 42 percent are classified as English learners.

But success hasn’t protected charter schools like Voices from a growing wave of criticism. Ask founder Frances Teso about the future, and she says, “You’re catching me in this place where it’s pretty depressing and pretty pessimistic, at least from my sort of view … maybe I need to retire.”

Teso’s attitude is understandable. After years of relatively uncomplicated bipartisan support, charters like Voices are under fire in national progressive discourse. Sen. Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign recently released a long list of education ideas, but his proposals to ban (relatively rare) for-profit charter schools and cut off federal grants supporting charter school growth attracted by far the most attention. Sen. Elizabeth Warren recently faced a cascade of criticism for the sin of simply being introduced at an event by a teacher who once worked for a charter school.

These national dynamics are feeding — and feeding on — similar political trends in California. New governor Gavin Newsom has moved quickly to shift regulations governing charters, and state legislators are exploring ways to slow, or cap, the growth of charter schools in the state. For the moment, Teso says that Voices’s plans to expand to serve more of “the kids who need us the most” have largely been shelved. At present, the school serves just over 1,100 students across three elementary campuses and one K-8 campus.

Schools like Voices weren’t always so controversial on the left. For years, many progressives saw charters as a means of giving historically underserved families options outside of the neighborhood schools they could afford to purchase through the real estate market. They also worked to make that possibility real. Charter school performance varies across the country, but research suggests they tend to do best in places defined by progressive politics — the District of Columbia, Boston and Newark, for example — where these schools face strong oversight and accountability for student outcomes.

To that end, Teso launched the first Voices school in the same school district that she attended as a student — and where she worked as a teacher — because she was frustrated that students like her were not being served well. She’d arrived in college feeling betrayed. “I was so unprepared, I was not set up for success, I had moments of resentment,” she says. “Why wasn’t I prepared, why was I tricked? Why was I told that I was a good student and here I am in remedial classes and struggling?”

As an English language learner from a low-income family, Teso had a slim margin for error. Her mother was a teenager who’d dropped out of high school, and her father was a Mexican immigrant who’d left school in third grade. “We checked all the boxes,” she says. “I went into kindergarten, I spoke only Spanish.”

Teso’s narrative, her schools, her life’s work — they’re suddenly out of fashion with progressives. Critics argue that, unlike charter schools, district schools have little control over which students enroll at their campuses; districts simply receive the students who happen to live nearby.

This critique is concerning, but charters are the wrong target. No single district school is required to serve all students in its community; unlike charters, district schools’ enrollments are usually filtered by race and/or socioeconomic class through the real estate market. Traditional public schools regularly engage in additional efforts to curate their student bodies. They frequently establish academic “tracking” systems and/or launch selective school programs that sort struggling students from their peers. These initiatives often exacerbate existing patterns of racial and socioeconomic segregation.

What’s going on? Teacher strikes in Oakland, Los Angeles and Sacramento focused attention on charters in California. Teachers union leaders have argued that charter schools, which are generally not unionized, use education funding that would otherwise go to (generally unionized) district schools.

And yet, this zero-sum framing isn’t just empirically suspect. It also brings up the most important question: Why do families leave district schools in the first place? Juan Carlos Villaseñor, principal at Voices’ Morgan Hill campus, says that Voices appeals to different families for different reasons: Many first-generation immigrants send their children because the Spanish-language instruction makes it easier for them to connect with the school and community. Many second- or third-generation immigrant parents who lost their Spanish during California’s two decades as an English-only state see the school as a way to give their children access to Spanish language and Hispanic culture.

I asked a few Spanish-speaking parents at Voices about this. They agreed to speak with me, but they asked me not to use their full names, after referencing the present state of immigration politics. Luis says, in Spanish, that he sends his children to Voices because they’ll have more opportunities: “[they’ll have] more jobs, better careers, more money. But it’s also the culture, the connections to our culture.” Voices understands children better than other schools, he says. “They treat them like they’re important, and they also expect more of them.”

Diana and Natalí each have a first-grader at Voices. Diana says, in Spanish, that she chose it “because it was our only bilingual option here.” Natalí jumps in: “Oh, and the schedule! They are here a few hours more each day, and it helps them progress.” Charter parents across the country frequently make similar arguments — they see their children’s schools as opportunities, as lifelines.

“These big debates, charter versus non-charter, I sometimes lose track,” says Villaseñor. “I became an educator because I like being around kids and seeing people learn.” Working at Voices, he said, was an “opportunity to keep learning and keep growing. If something doesn’t work, we change it. That’s the mentality in this school. Our communities deserve that.”

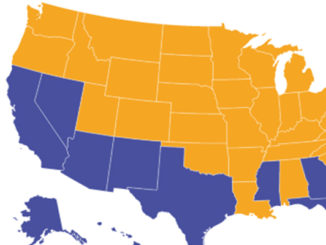

Various campaigns now see policies targeting charter schools as a political opportunity. But it’s also clear that Democratic criticism of charters splits along racial lines — majorities of Democrats of color support them. A party that increasingly relies upon a diverse base of voters should be careful about catering to white Democrats who oppose charters. After all, what could be more progressive than successful, hardworking schools led by educators of color and organized around affirming students’ language and cultures?

Meanwhile: Will Teso retire? She pauses, then says she plans to continue doing the same work for students while trying to “stay under the radar.”

Conor P. Williams is a fellow at The Century Foundation. Previously, Williams was the founding director of New America’s Dual Language Learners National Work Group. He began his career as a first-grade teacher in Brooklyn. He holds a Ph.D. in government from Georgetown University, a master’s in science for teachers from Pace University, and a B.A. in government and Spanish from Bowdoin College. His two children attend a public charter school in Washington, D.C.