by Richard V. Reeves

America and I share a birthday: July 4th. This is an agreeable coincidence, especially for a Brit. The whole nation seems pleased that I’ve chalked up another year.

One of the attractions of America for me, and millions of other immigrants, is the national spirit of possibility—the ideal of a classless, open society in which birth is neither rank nor destiny. In short: the American Dream.

Equal and independent

This moral imperative was an animating force behind the Declaration of Independence itself, and the proclamation that “All men are created equal.” In his first draft of the document, Thomas Jefferson was in fact more expansive and specific, writing that all were created “equal and independent.”

The declaration was a statement of America’s independence from Britain, but also of the independent stature of each and every American. Needless to say, at this time in U.S. history, this meant every white male, and we are still living with the consequences of this deep hypocrisy. But the ideal remains. Recent survey evidence suggests that black, Hispanic and Asian Americans are more fervent believers in the American Dream than their white peers.

The United States was to be a self-made nation comprised of self-made citizens. Alexis de Tocqueville recounted in his Democracy in America the young nation’s “passion for equality,” while Abraham Lincoln extolled the American “genius for independence.”

Egalitarian individualism

This ideology, which I’ve elsewhere dubbed “egalitarian individualism,” is one reason America never cultivated a strong socialist movement. The class hierarchies of the Old World were not part of the American experiment. As Chris Hayes writes in his book, Twilight of the Elites, upwardly mobile Americans “rise from their class, not with it.”

This individualist ethos frustrates many on the left, but the truth is that there is little sign of it losing its grip on the collective imagination. The real problem is not that America is failing to live up to European egalitarian standards—as set out in recent treatises by Frenchman Thomas Piketty and Englishman Anthony Atkinson—but that we are failing to live up to American egalitarian standards, as judged by equality of opportunity.

The chances of moving up the income ladder from the bottom are no higher in the United States than in other advanced economies. All the talk about Horatio Alger is just that: talk. And, if anything, the perpetuation of elite status at the top of the ladder is stronger in America than elsewhere. When position on the top and bottom rungs is a strongly inherited condition, the idea of America is in trouble.

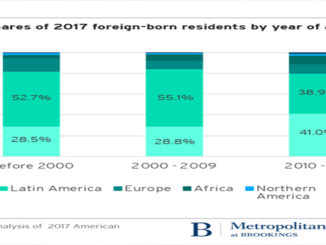

There are of course a huge array of factors standing in the way of greater social mobility: family stability, parenting, contraception, schooling, community norms, skills, post-secondary education, access to jobs, employment security, geographical mobility, zoning and affordable housing wage volatility…the list goes on and on. The lack of social mobility in the United States is a complex, multidimensional, multigenerational problem.

Race gaps in opportunity

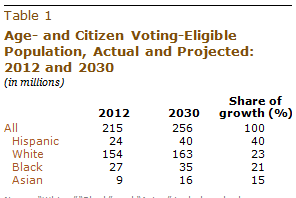

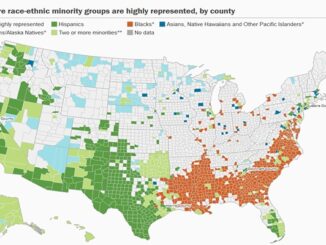

But one issue bears particular attention, one that intersects with and reinforces many of the others: the distinct mobility patterns of black Americans. There has been an enormous expansion of opportunity for black Americans in the last half century, but given the starting point, it would have been almost impossible for there not to have been. But the remaining gaps look stubborn. The gap in real household income between whites and blacks has barely moved for a couple of decades, and the wealth gap has in fact widened as a result of the recession.

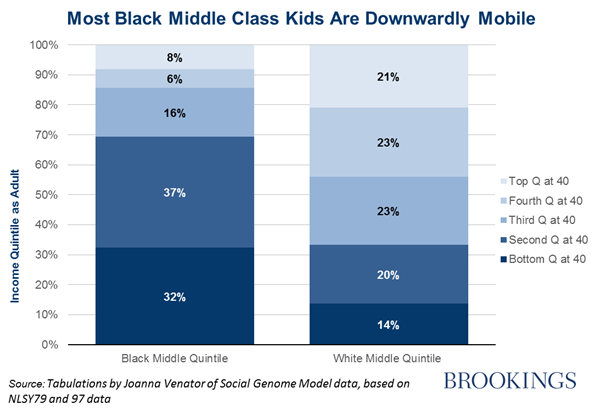

Surprisingly, most black children born into a middle-income family will fall down the income ladder, while most white children will not. Recent events in cities around the country have shone a light on a deep, and deeply uncomfortable, problem: being born black matters very much more than it ought to for life chances in 2015.

The ethos of egalitarian individualism is shared by Americans of all races. If anything, support for European-style redistribution has fallen among black Americans in recent years, according to a paper published by Brookings. But the opportunities and tools needed to lead a fully independent, “self-made” life do not appear out of thin air. They are created and destroyed in our communities, relationships and institutions.

Now, or never?

The American Dream of equal independence for all, regardless of color, has not been achieved. But it remains within reach. As fireworks burst overhead across the nation and church fires smolder in the South, alongside the celebration needs to be a determination to live up to America’s founding ideal for all Americans: now, or perhaps never.

Richard V. Reeves is a senior fellow in Economic Studies at Borookings, where he holds the John C. and Nancy D. Whitehead Chair. Richard is Director of the Future of the Middle Class Initiative and co-director of the Center on Children and Families. His research focuses on the middle class, inequality and social mobility.