by Mark Keierleber

This article was originally published at The 74.

An invisible line separates the school system in Waterbury, Connecticut from neighboring districts, but in many respects, they’re oceans apart. A significant share of students at the district, which is located in one of America’s wealthiest states, is nonwhite and poor. Drive a few miles in any direction from Waterbury, however, and you’ll find the exact opposite.

In fact, Waterbury is America’s most “isolated” school system, according to a report released Thursday by the nonprofit EdBuild. In Waterbury, where 82 percent of students are nonwhite, the district brings in about $16,000 in per-pupil school funding. But in each of the eight districts that share its borders, schools get significantly more money per student. Their student bodies are whiter. In the neighboring Thomaston School District, for example, just 8 percent of students are nonwhite and the education system brings in more than $20,000 per pupil.

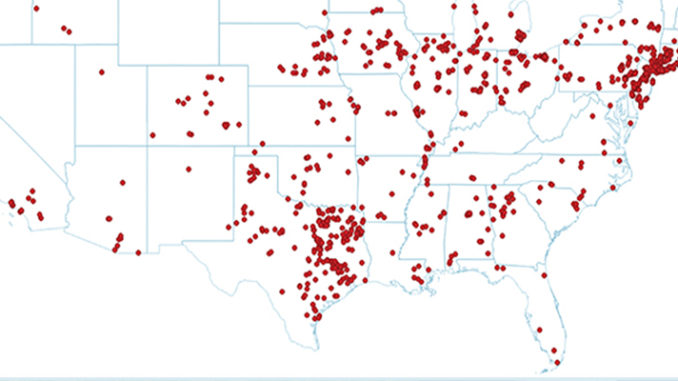

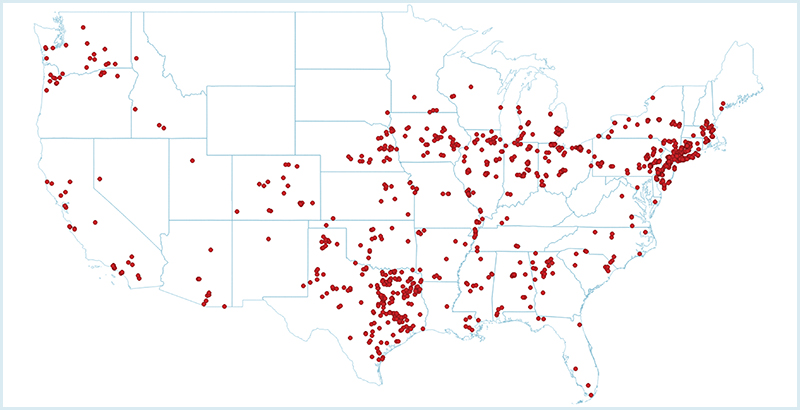

Though Waterbury tops the list, EdBuild found nearly 1,000 school district borders where students are sharply divided in a way that creates a system of winners and losers, according to the report. On the losing side of the borders are nearly 9 million students in districts that get $4,207 less per pupil than affluent districts next door. Across the country, EdBuild found a total of 969 instances of school district borders where revenue gaps exceeded 10 percent and differences in racial makeup exceeding 25 percentage points.

While America’s long history of housing segregation plays a role, the report argues that a 45-year-old Supreme Court ruling stands in the way of school integration across district lines. The case, Milliken v. Bradley, found that the government cannot mandate racial integration across school district borders. Because of that ruling, the report argues, wealthy communities are using district borders to effectively hoard resources.

The bulk of the problem, the report said, is that local property taxes generate the bulk of school funding. Though states try to make up funding gaps by providing low-income districts with additional money, they’ve failed to meet demand, said Rebecca Sibilia, EdBuild’s founder and CEO.

“States are running to try to catch up and, because they’re not willing and not brave enough” to address inequities created by school district borders, she said, “they’ve put themselves in an impossible position to ever create the kind of equity that we need because our wealth divide is growing.”

The latest EdBuild report is part of a series examining how district borders can create inequities in America’s public schools. In another recent report, researchers found that school districts serving predominantly nonwhite students get $23 billion less in state and local funding each year than those where students are predominantly white — even though they educate roughly the same number of children.

Despite the Milliken ruling, states have several options to address racial segregation and funding disparities created by district borders. Lawmakers could revise education funding systems so that rely less on local property taxes, for example, or they could redraw school district borders in a way that more equitably distributes education resources. But Sibilia argues, state-level lawsuits may be the best bet.

“Our work has created a pretty compelling case for parents and local advocates to really get loud on this and bring this issue to the courts,” she said. “We’ve got a huge treasure trove of data out there that clearly demonstrates that there’s a disparate impact in our funding system.”

The report found some of the most problematic school district borders exist in New York, New Jersey and California. New Jersey, for example, has more than 600 public school districts. On average, the state’s advantaged districts get 35 percent more in per-pupil funding than their lower-income neighbors.

But a desire for local control of schools, Sibilia argues, often leaves many students behind.

“This idea that we can withhold and keep our property tax wealth for just our schools is wholly unique to education,” she said. “The cure for cancer may be sitting in the head of a student who goes to New York City Public Schools. Would you honestly say that you wouldn’t chip in to make sure that student gets a quality education and can access the kind of knowledge that would be required in order for them to actually develop that cure?”

EdBuild’s years-long focus on funding gaps and racial segregation between America’s school districts will soon come to an end. Sibilia said the nonprofit plans to close shop next year. Though EdBuild still has a few more reports in the pipeline, she said the group achieved its goal of highlighting America’s school funding inequities.

“Its incumbent upon us to leave the space so that other voices can emerge on this and new ideas can come forward,” Sibilia said.

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.