by Michael J. Petrilli

It’s long been understood that, on average, there’s a strong relationship between a child’s socioeconomic status and his or her academic outcomes. It’s also the case that when poor families become less poor—either because of more “market income” or due to social programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit—their children tend to do better in school. That’s not surprising, given that kids only spend approximately 9 percent of their first eighteen years of life in school. So it stands to reason that improved economic conditions for lots of children should be associated with improved results on achievement tests. Is that what we were seeing before the Great Recession struck?

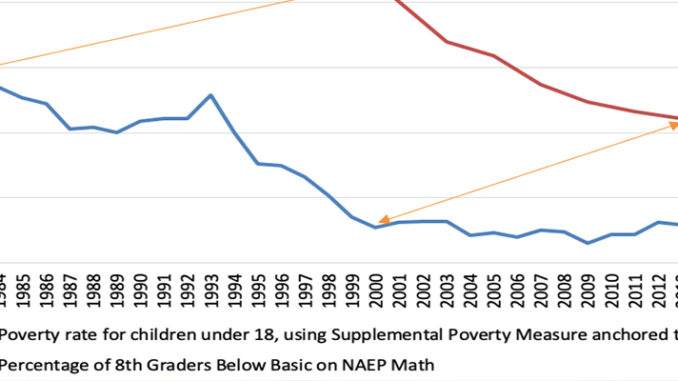

To find out, we’ll start by charting the supplemental child poverty rate against the “below basic rate” for the fourth-grade National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in reading. Both measures are dichotomous—you’re either above or below the line in each case. And we want both of these rates to decline over time.

Helping families escape poverty is not the only goal we might have for social policy. We’d also love to see significant upward mobility into the middle class and beyond. Likewise, moving students to NAEP basic isn’t nearly enough if we want children to be on track for college and career. “Proficiency” is still the gold standard.

But let’s not allow our desire for the gold to blind us to some worthy bronze. Reducing the child poverty and below-basic rates is an important milestone on the way to bigger and bolder goals.

Without further ado, let’s take a look.

Figure 1. The “below basic in fourth grade reading rate” versus the supplemental child poverty rate

What immediately jumps out from this picture are the similar inflection points in both lines—with changes in the “below basic” rate lagging changes in the child poverty rate by about seven years. From 1993 until 2000, the supplemental child poverty rate declined from 28 percent to 18 percent—a 10-point drop, or 36 percent reduction. From 2000 until 2007, the percentage of fourth graders reading below basic on NAEP declined from 41 percent to 33 percent—an 8-point fall, or 20 percent reduction. The supplemental child poverty rate hit an all-time low in 2009, before ticking up in 2010. And the below-basic rate hit an all-time low in 2015, before ticking up in 2017.

Interesting.

To be sure, the pattern isn’t perfect. Most notably, child poverty declined in the 1980s, and yet reading performance in the early 1990s got worse. (Perhaps because of the whole-language craze?) But over the past twenty years, the two lines appear to be moving generally in the same direction.

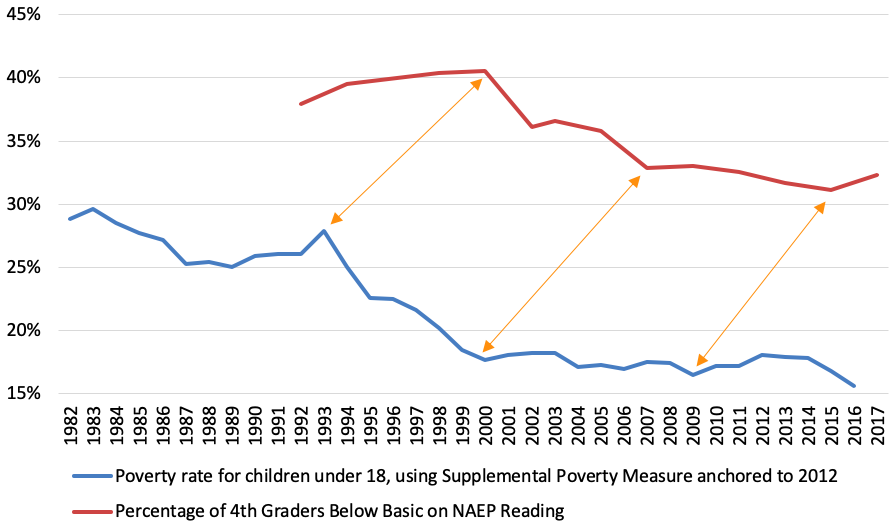

Now let’s see how it looks for eighth graders.

Figure 2. Percentage of eighth graders below basic on NAEP reading, supplemental child poverty rate

This time, changes in the below-basic rate lags changes in the child poverty rate by about thirteen years.

After declining for most of the 1980s, the supplemental child poverty rate started to rise in 1989 with the onset of a recession, and hit a peak in 1993 before plummeting throughout the remainder of the 1990s. A similar pattern is seen with the rate of eight graders reading at a below-basic level—but thirteen years later. This rate declined throughout the 1990s. Then in 2002 it started to rise, thirteen years after 1989. Three years later, in 2005, it started declining again, twelve years after 1994.

The same pattern can be seen in later years, as child poverty rose slightly with the weakening economy in 2000. Thirteen years later, the below-basic rate rose, too.

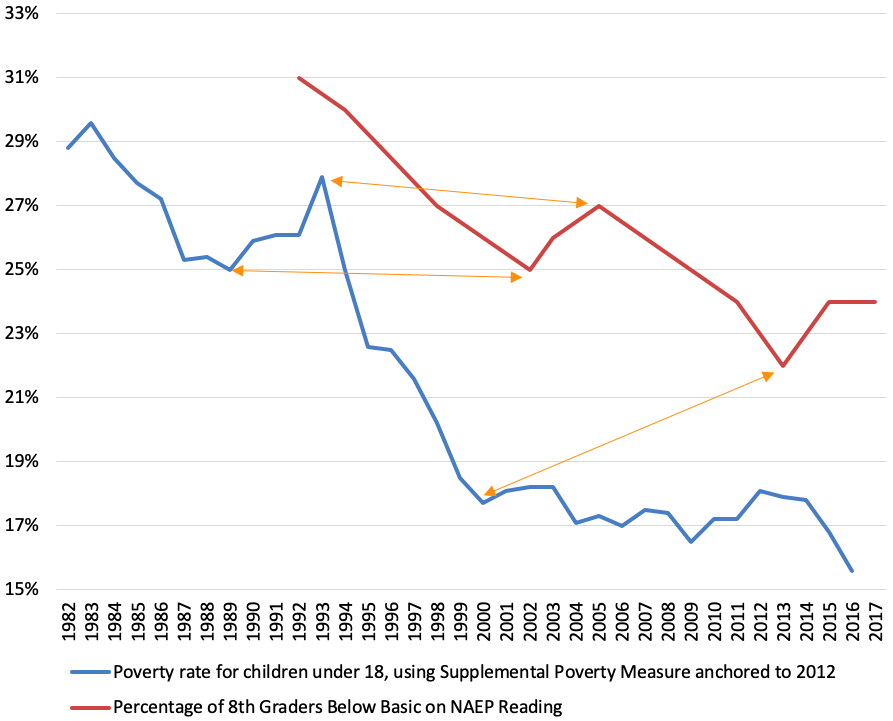

And it’s not just in reading. We can glimpse similar patterns in math.

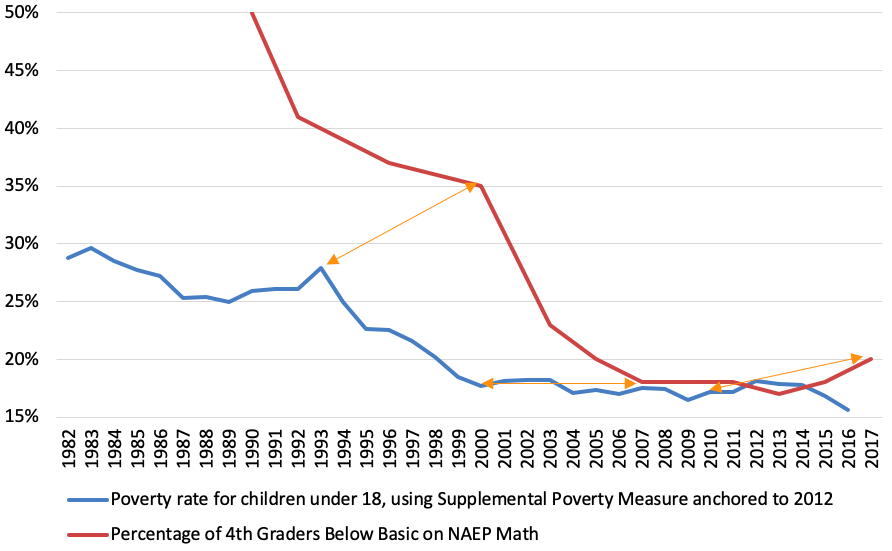

Figure 3. percentage of fourth graders scoring below basic on NAEP math, supplemental child poverty rate

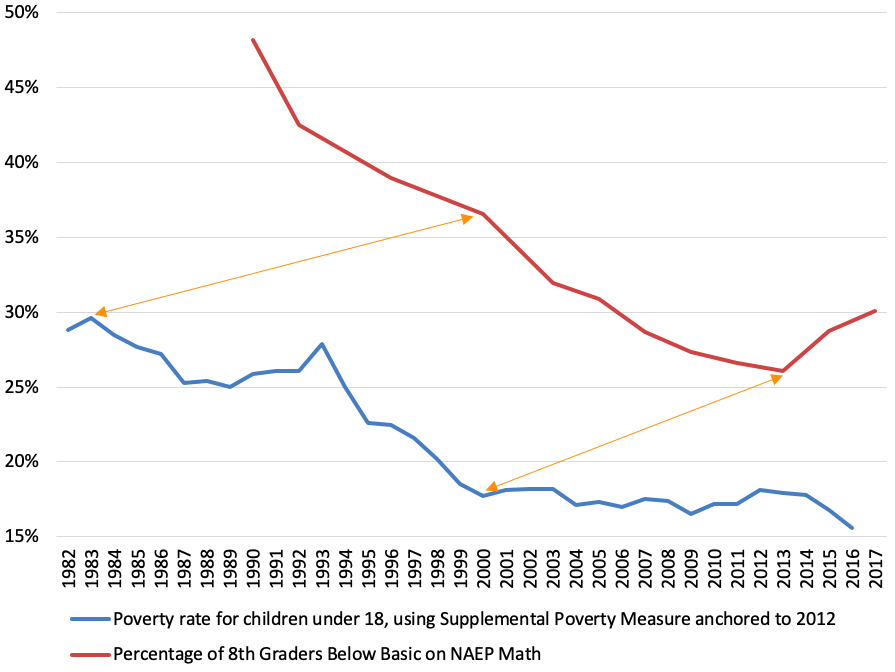

Figure 4. Percentage of eighth graders below basic on NAEP math, supplemental child poverty rate

Now is a good time for me to issue a disclaimer: I may just be a policy wonk instead of a trained social scientist, but even I know that correlations between a few lines don’t count as solid evidence that the falling child poverty rate drove improvements in student achievement. But it sure seems that there might be a relationship at work—namely that the prevailing economic conditions at the time of a cohort of children’s birth (or shortly thereafter) appear to be related to the cohort’s later achievement—at least at NAEP’s below-basic level.

Again, this is speculative. I would love for a scholar with econometric chops to dig into the question of how much of the progress in student achievement can be explained by the improving economic conditions for poor kids and their families, and how much credit should go to schools and various efforts to reform them. My hunch is that the declining child poverty rate deserves some, perhaps much, of the praise. It would surely vary by subject, grade, and time period—and might help us understand when and how our schools outperformed what we’d expect given socioeconomic conditions. To my friends in academia: Please help!

I can imagine that my hypothesis—that the big achievement gains of the late 1990s and early 2000s mostly shouldn’t be credited to schools or school reform—will be depressing to my colleagues in the reform movement. I can also picture some reform opponents cheering these arguments, given that they have long pointed out that test scores are strongly correlated with socioeconomics, and that reformers have been ignoring reality when we argue that schools should and could be getting much better results.

But my posts in coming weeks are likely to further complicate this narrative. I will argue:

- That there’s strong evidence that changes in policy deserve some credit for improved achievement too—especially the advent of school accountability systems.

- That if improving socioeconomic conditions largely explain the improving test scores of the late 1990s and early 2000s, then declining socioeconomic conditions during and after the Great Recession may largely explain the “Lost Decade of Educational Progress.”

- That while socioeconomic trends might be the major drivers of achievement trends at the national level (with the accent on “might”), there has been significant variance at the state level. And—spoiler alert—the most reform-minded states are among those that have beaten the socioeconomic curve.

There’s much more to cover. Stay tuned!

Mike Petrilli is president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, executive editor of Education Next, and a Distinguished Senior Fellow for Education Commission of the States. An award-winning writer, he is the author of The Diverse Schools Dilemma, and editor of Education for Upward Mobility.