by William Alan Reinsch, Jack Caporal, Beverly Lobo and Catherine Tassin de Montaigu

Late last week, the United States and Mexico reached an agreement in which Mexico pledged to take action to stem the flow of undocumented immigrants traveling from Central America to the United States in exchange for the United States holding off on imposing a 5 percent tariff on all imports from Mexico. However, the threat of those tariffs, which would escalate 5 percent each month after their imposition to a maximum of 25 percent, has not fully abated. After the agreement was reached, President Trump tweeted that the United States would impose the tariffs if Mexico’s Congress of the Union did not approve the deal. The Trump administration could move forward with the tariffs if it determines that Mexico is not meeting its commitments, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said after the deal was reached. Given the emphasis President Trump places on both immigration and trade, it is not far fetched to assume the threat of tariffs on Mexico could be revived. As a result, the Scholl Chair in International Business has prepared the following questions and answers “just in case.”

Q1: How would President Trump’s time-escalating tariffs against Mexico affect businesses and consumers?

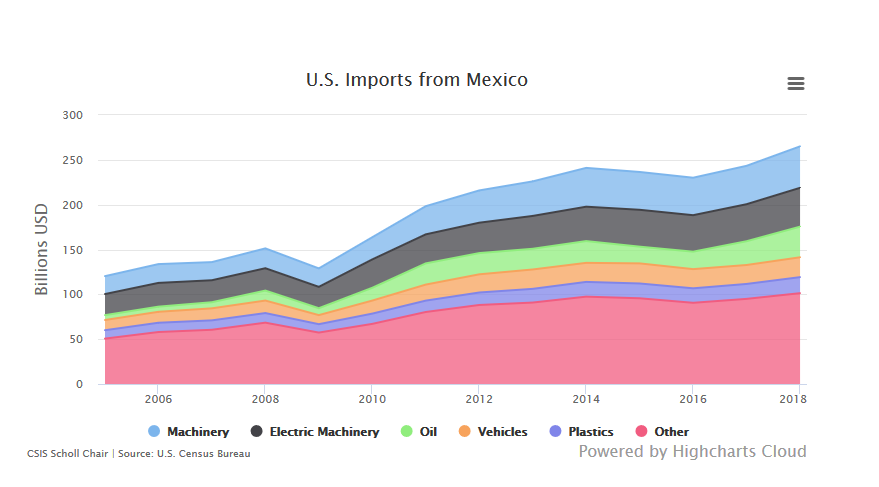

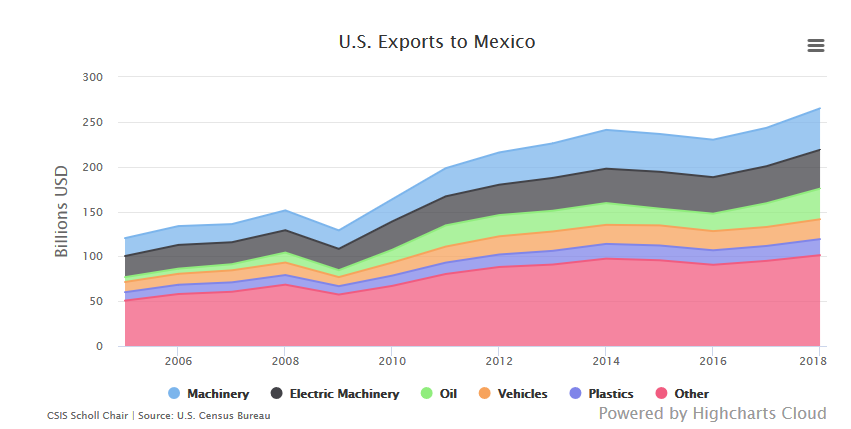

A1: In short: negatively. In 2019, Mexico surpassed China to become the United States’ largest trading partner. Through April, trade with Mexico comprised 15 percent of all U.S. trade—some $203 billion of imports and exports. Over the course of 2018, more than $1.67 billion in trade crossed the U.S.-Mexico border daily, with the United States exporting $265 million worth of goods to Mexico and importing $346 billion. Top imports from Mexico include machinery, electric machinery, crude oil, and vehicles and parts.

Businesses scrambled to respond to the threat of tariffs. Some automakers had begun to rush component part shipments to beat the Monday deadline, while others opted to delay vehicle deliveries. The uncertainty will have lasting effects in terms of added costs to businesses and disruptions in supply and demand chains. If the tariffs were imposed, U.S. companies importing goods from Mexico would likely have shouldered the initial costs, lowering profit margins. Businesses that send goods back and forth across the border throughout the manufacturing process, like those in the auto industry, would have been particularly affected by steadily increasing tariffs. According to a Reuters report, Toyota issued an email to its U.S. dealers estimating the tariff changes could add between $215 million and $1.07 billion in costs to its major suppliers.

In order to regain their profit margin, companies may have passed the increased costs on to consumers. Reports suggest that these proposed tariffs combined with other tariffs the administration has imposed on China and Europe would have offset the initial income gains from Trump’s tax cut. Companies may have been forced to lower wages, institute hiring freezes or lay off workers, reduce planned investments, or introduce other cost-cutting measures.

The president’s ultimate hope, in addition to stemming undocumented immigration into the United States, was to make doing business in Mexico so expensive that U.S. companies would opt to invest in supply chains within the continental U.S. However, this goal assumes that supply chains will not be diverted to other countries that can fill production at a lower cost than in the United States. In the meantime, both the United States and Mexico would suffer from tariffs. Secretary of Agriculture Victor Villalobos of Mexico said, “[a] 5% U.S. tariff would decrease [US-Mexican agricultural] trade by $3.8 million a day.” U.S. tariffs would likely be met with retaliatory tariffs from Mexico on U.S. goods, which could slow U.S. exports and further upset supply chains.

Businesses and consumers would feel more pain as the tariffs increase over time, but it’s unlikely rising tariffs would achieve the president’s ultimate goal—stopping the flow of undocumented immigrants traveling through Mexico. This position assumes that Mexico can resolve all immigration issues in Central America. Instead, the administration’s approach could exacerbate the immigration crisis. Levying tariffs on Mexico will hurt the Mexican economy, which will make the country less capable of dealing with migrant flows from Central America and policing the U.S.-Mexico border. A weak Mexican economy would ultimately discourage Mexicans and Central Americans from remaining in their respective countries and instead further incentivize immigration to the United States.

Q2: What options would Congress have if the tariff threat is revived?

A2: Given that President Trump threatened to use the broad authority enumerated in the International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA) to effectuate his immigration policy goals, there is little Congress can do without a bipartisan super majority. Although the president is required to consult with Congress before independently declaring a national emergency, there are few other statutory requirements limiting IEEPA’s use. Because it is in the president’s sole discretion whether there has been “any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States,” this novel use of IEEPA will likely not go uncontested. While former presidents have not shied away from using this statute to impose economic sanctions, proponents for tariffs on Mexico would likely argue the trend from country sanctions to individuals illustrates the statute’s flexibility. Although IEEPA has not been used to impose tariffs, any court challenge arising out of the president’s conduct would likely be rebuffed given the statute’s overall broad language.

IEEPA does allow Congress to end the declaration of an emergency via passage of a disapproval resolution. However, such a resolution is subject to a presidential veto, so Congress would have to muster a two-thirds majority in both houses to make their disapproval stick. Senator John Cornyn (R-TX), chair of the Senate Finance Trade Subcommittee, appeared ready to lead the charge against the proposed tariffs with his fellow Texan, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX). House Democrats also cried foul over the president’s threat; however, it is less clear if a supermajority could be mustered in the House to override a veto.

In a twist, the Trump administration had outlined two legal pathways to the tariffs: “the president could use the existing national emergency declaration on the border wall to impose the new tariffs or he could declare a second emergency to unlock new tariff authority.” Should the administration revisit the tariff threat via the first option and bipartisan efforts to block them come to fruition, the resolution could not only thwart the tariffs but the construction of the president’s border wall as well.

Congress already rebuked the president’s national emergency declaration to divert funding to wall construction in a 59-41 vote this spring. 12 Republicans voted against the declaration due to concerns about executive power. The president vetoed the resolution. However, if the administration opts to use the existing emergency declaration to levy tariffs on Mexico, the political equation could drastically shift. Members of Congress would be taking a vote on both the tariffs and the wall—each signature pieces of the president’s agenda. The president and other Republican politicians could effectively use that vote on the campaign trail either as a political bludgeon or point of praise.

Q3: How would tariffs on Mexico affect the rest of the United States’ trade agenda?

A3: This episode is the latest in a series of now-predictable maneuvers from the Trump administration, which consists of using the threat of tariffs or other economic sanctions as a hammer to go after the crisis de jour only to reach a face-saving agreement in the final hour. This approach has two impacts. The first impact falls on businesses and consumers by generating uncertainty about whether or not tariffs will be imposed. Businesses and consumers will become more likely to hold off on investments while the administration continues to threaten tariffs. That means businesses may hire less, expand slower, and make fewer long-term investments in areas like research and development or new facilities.

The second impact of the Trump administration’s approach is on U.S. credibility and the credibility of the global trading system. The administration’s trade negotiating history sends a bleak message to U.S. trade partners. Foreign governments may conclude that months of negotiation and economic cooperation will not stop the president from changing his mind and adopting a suddenly aggressive and adversarial stance. This was the case in this latest episode with Mexico, which followed painstaking negotiations to finalize the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and lift U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum. The Mexico episode also undercut the administration’s negotiating credibility in the trade arena and beyond. By using an instrument usually reserved for trade policy to threaten a foreign government over a separate issue, immigration, the Trump administration has indicated that it is willing to ignore its international trade obligations to gain leverage in other policy areas. In this case, the damage has been done even though the tariffs were not imposed.

More immediately, Mexican officials insisted that the tariff threat had no bearing on the USMCA, President Trump’s signature trade agreement. Despite being on the path to ratification in Mexico and Canada, the USMCA already faces several existential threats in the United States. Some members of Congress as well as the business community warned that new tariffs on Mexico would make it more difficult for the administration to build support for the USMCA. U.S. tariffs may also cause Mexican politicians and leaders to second-guess the value of an agreement with the United States and be less politically inclined to cooperate with the United States.

William Reinsch holds the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Jack Caporal is an associate fellow with the CSIS Scholl Chair in International Business. Beverly Lobo and Catherine Tassin de Montaigu are interns with the CSIS Scholl Chair in International Business.