by William H. Frey

The Supreme Court temporarily blocked President Trump in its census ruling.

Thursday’s Supreme Court ruling temporarily blocking the insertion of a citizenship question on the 2020 Census is not yet cause for celebration for those who value the nation’s increasing diversity. Nor is it for those who are concerned about the implications of an inaccurate picture of the population. The temporary decision still leaves the door open for the Trump administration’s most ambitious attempt to keep America white — in public perception and with fraught political consequences.

The Supreme Court’s 5-to-4 decision upholds, for now, the rulings of several lower courts and the opinions of scores of state attorneys general, professional associations, former census directors and in-house Census Bureau staff — all testifying that adding a citizenship question would lead to a flawed 2020 Census and to undercounts of large segments of the nation’s foreign-born, noncitizen, Muslim, Hispanic and Asian populations. And it would thereby rob them and their communities of political power and government resources.

Casting the deciding vote to send the case back down, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that “the sole stated reason” for adding the citizenship question “seems to have been contrived.”

“We are presented,” he continued, “with an explanation for agency action that is incongruent with what the record reveals about the agency’s priorities and decision-making process.”

This message, however process-oriented, flies in the face of the Trump administration’s manufactured reasoning for attempting to add the question.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross maintains that the addition of this question is needed to enforce the Voting Rights Act, which stipulates that citizens of different racial groups be considered in the drawing of legislative districts. But existing data, such as the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, has long been used for this purpose.

President Trump’s immediate threat on Twitter to potentially delay the 2020 Census adds just more fuel to the fire on this exceptionally contentious issue.

Should the Supreme Court make a final decision later this summer or in early fall, and vote in favor of the administration, some states may try to switch the basis for drawing legislative districts from “one person/one vote” to “one voting-age citizen/one vote.” That is, the availability of citizenship status information for every individual would tempt states under Republican control to draw legislative districts on the basis of eligible voter populations — citizens 18 and older — rather than the total population, as is currently done. This will make all districts in a given state whiter — generally much whiter — and provide the wherewithal for even greater Republican-favored gerrymandering than was possible in the past.

In 2016, in Evenwel v. Abbott, the Supreme Court ruled that states were allowed to use their total populations to determine districts, but it did not rule on the use of eligible voters for this purpose. It left the door open, and that inspired proponents of the citizenship question to lobby the administration to add it to the 2020 Census.

The real reason for attempting to make this late addition to the census is to gain long-term political advantage for Republicans by making more legislative districts appear to be whiter than they are. This political strategy was suggested in internal memos on the subject between Ross and anti-immigrant proponents Stephen K. Bannon and Kris Kobach. Recently uncovered communications between a now-deceased Republican gerrymandering specialist, Thomas Hofeller, and the Justice Department made more explicit the case that adding the citizenship question would be advantageous to “Republicans and non-Hispanic whites.”

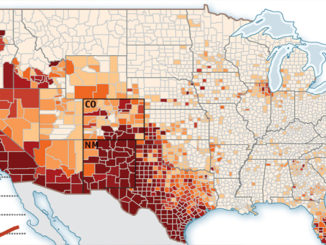

New Census Bureau research reports that the citizenship question could reduce response rates among households with at least one noncitizen by up to 8 percent, altering its earlier projection of a 5.8 percent decrease in responses. According to American Civil Liberties Union attorney Dale Ho, this could lead to an undercount of 9 million people in the 2020 Census, “more people than in New Jersey, our 11th largest state.” My analysis of the American Community Survey shows which groups would be most negatively affected by this under-reporting: Hispanics, Asians, young people, and urban residents. Their reduced response would lead to a flawed reapportionment of Congress under-representing high immigrant states.

With the case now back in the hands of lower federal courts, Republicans may still yet politically profiteer off an eventual census that would engender fear and noncompliance on the part of immigrant and minority groups that Trump has railed against. Should the Supreme Court make a final decision over the next few months before the questionnaire printing deadline arrives (perhaps as late as October, if Trump’s threat to delay the census does not come to fruition), the immediate impact of a flawed census, in how it reapportions congressional seats across states, could lead to seat reductions in both blue (e.g. California) and red (e.g. Texas) states with large immigrant populations.

The longer-lasting advantage for Republicans of having the citizenship question answered by all who take the census would be to change the rules in which the way legislative districts within states are drawn. Texas and Arizona have already expressed interest in using citizen voters as a basis for legislative districts rather than all residents. The census citizenship question would give them the tools to do so, providing them the wherewithal to draw wider, whiter districts beyond urban boundaries, thus diluting the representation of younger, diverse and denser populations that make up larger parts of a state’s total population than the voting-age population. In so doing, the interests of the latter groups in state and federal funding for education, affordable housing, health care and family services would be diminished.

Why would this make districts much whiter? This is based not only on the fact that the noncitizen voting-age population is less white than the voting-age population. It is also because the under-18 population — now included in total population figures for redistricting — is more racially diverse than adults of voting age. The most recent census estimates from the 2017 American Community Survey show that the nation’s total population is 61 percent white, but its adult voting population is 68 percent white. The main reason for the difference is that the underage population is 51 percent white.

The likelihood that the citizenship question will be added to the 2020 Census is now uncertain — though we can be sure that the Trump administration will not give up quietly in its pursuit of making America white again. However the next few months shake out, it is likely that the “one person/one vote” basis for redistricting will be continue to be challenged by Republican-dominated states hoping to keep their legislative districts whiter and older than their populations. It is unfortunate that the potential even exists to create a lag between the nation’s vibrant and highly diverse population and the makeup of its legislative districts. The good news is that these younger, diverse populations will soon become part of the body politic. Perhaps then, when making decisions about political representation, all branches of the government will come to recognize that the nation’s demographic future should not be ignored.

William H. Frey is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and is the author of “Diversity Explosion.”