by Kevin Mahnken, The74

Brown v. Board of Education has been called the Supreme Court’s finest hour, and it is perhaps the most critical single event in the history of American education.

In a unanimous ruling, the Supreme Court swept aside more than a half-century of legal segregation, paved the way for the groundbreaking civil rights legislation of the 1960s and ushered in decades of government-led efforts to mitigate racism in public schools.

Sixty-five years later, the case’s legacy is undeniable: More black students than ever before are graduating from high school and attending college. The achievement gaps between black and white students have narrowed, albeit slowly, and long-term outcomes for black people — from life expectancy to career earnings — have improved. The gradual dismantling of a state-sanctioned system of separate schools has yielded, at least in part, a less bifurcated society generally.

But over the past few years, a worried consensus has emerged about the long-term effectiveness of our campaign to integrate schools. Following aggressive desegregation measures taken in the 1970s and ’80s, particularly in the South, states and school districts have taken their foot off the gas over the past 25 years. A slew of experts now claim that American schools have gone backward, exhibiting greater levels of racial isolation now than 40 or 50 years ago.

In two-thirds of one century — the lifetime of one baby boomer — the American education system commenced a radically ambitious project to bring black and white students together, courted massive political upheaval, then watched as many of the gains it had achieved slowly melted away. Now the question becomes: Where does Brown v. Board stand in an America that looks radically different from the one in which it was first issued? What is the future of school integration in the absence of a white majority?

2019 vs. 1954

The question of equity in educational opportunities remains as relevant now as it was at the dawn of the civil rights movement. But the context of 2019 could hardly be more different from that of 1954.

Simply put, Americans are vastly more diverse, and more socially integrated, than they were at the time of Brown v. Board. Whereas white people accounted for roughly 90 percent of all Americans in 1950, their share of the population has steadily dropped since 1970, and Census projections indicate that the United States will reach minority-majority status as early as 2045. By some analyses, K-12 schools have reached that point already.

Notably, that trend has been driven almost exclusively by increasing levels of immigration from Latin America and Asia. Kfir Mordechay, a professor of education at Pepperdine University, said that this change in our population mix has led to a generational split: Baby boomers and older members of Generation X are still disproportionately white, while those under the age of 40 are drastically less so.

“If you look at the demographic structure of our society 50, 60 years ago, it was pretty much biracial — our society was, for the most part, black and white,” he said. “This was certainly the case in the 1950s, when we had [Brown v. Board]. Beginning in the 1970s, we started having mass migration from Mexico, mainly, and that completely changed the complexion of many of our states. Right now, it’s changing the complexion of most of the country.”

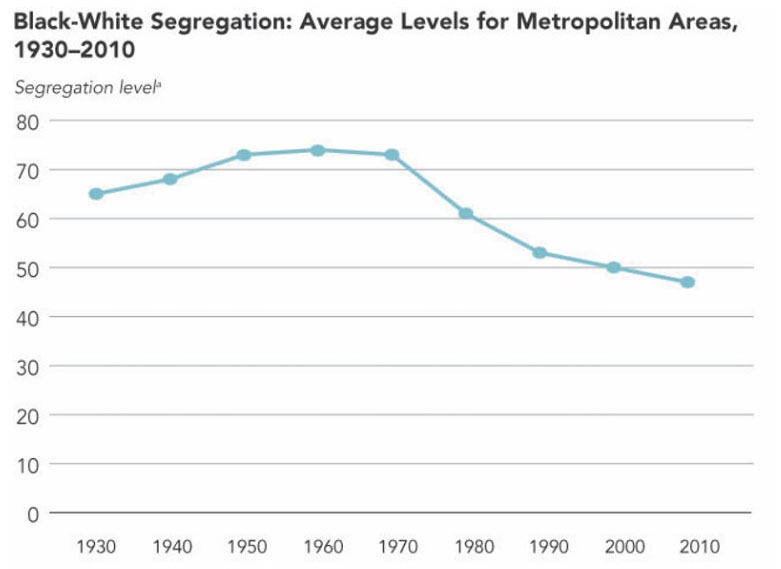

In addition to being more diverse, the population is much more racially mixed, especially in major cities. In his 2014 book Diversity Explosion, demographer William Frey showed that patterns of residential segregation abated in the first decades of the 21st century. Though black-white integration is still very much a work in progress, 93 of America’s 100 largest metropolitan areas saw declines in segregation between 1990 and 2010, Frey found.

The phenomenon of gentrification, through which affluent and educated whites have swept back into the urban cores from which their parents fled in the ’60s and ’70s, has yielded newly heterogeneous neighborhoods at the same time that thousands of black families have moved en masse into suburbs. The results have defied old stereotypes about class, race and geography in the United States: Urban whites are increasingly educated, suburban poverty is growing quickly, and Hispanics have supplanted blacks as the nation’s largest minority group.

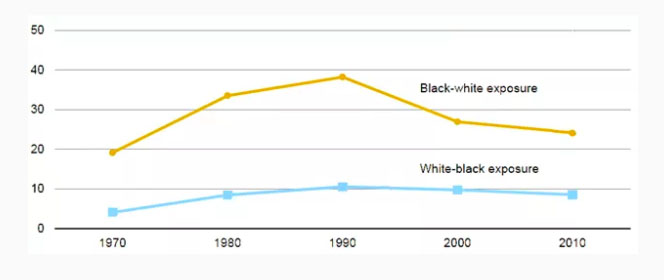

And yet schools don’t seem to have followed suit. Black-white exposure (i.e., the amount of white students enrolled in the average black student’s public school) has declined precipitously since 1990.

Joshua Starr, CEO of the teachers’ professional organization PDK International, noted that changing residential patterns alone weren’t doing enough to bring white and minority students into the same classrooms. A former district superintendent in Maryland and Connecticut, he said that middle-class white parents are still instinctively reluctant to enroll their children in substantially integrated schools.

“Even if districts are changing, schools may not be,” he said. “We’re not seeing stories of schools or districts that have really cracked the nut.”

The movement toward greater residential diversity was obvious, but insufficient, Starr said. White parents now have too many exit ramps from integrated public schools — including the recent vogue for wealthy communities to “secede” from their native school districts, taking their students and property taxes with them. Going forward, he said, options like those will continue to tempt white families.

“Two dynamics will happen. One is that the typical school district will get more diverse, which should theoretically drive more diverse schools. But you’ll also then see that white people with means will continue to resegregate: creating their own school districts, charters, private schools, whatever it may be. And I think you’re seeing both those things happen right now.”

Mordechay said that modern-day integration efforts are hampered in part by public dialogue around the issue. Too many well-intentioned advocates couch the debate in terms of equity, emphasizing the well-known academic gains realized by minority students who share classrooms with white peers. Instead, he tries to appeal to self-interest, underlining the necessity of preparing students for the multicultural world that awaits them outside of school.

Existing research strongly indicates that the academic performance of white and well-off students is not harmed by integrated schools. Not only that, they actually achieve social benefits from the presence of those who haven’t shared their advantages — a study of schools in New Delhi that desegregated on class lines found that comparatively rich students became more generous, less likely to discriminate against their poorer classmates and more likely to socialize with them.

“When I have conversations with parents who have choice — more affluent folks, mainly white parents — I really try to pivot away from this conversation around equity,” Mordechay said. “I try to frame it as, ‘Why should you do it, why is it good for your kid?’ rather than saying, ‘You know, this is good for society in 20 years from now, because it will create more equity in the long run.’”

Demographics or policy?

Even if more white families could be persuaded to desegregate, it’s not clear that their altruism would result in meaningfully different outcomes. In part, that’s because it’s unclear just how much the behavior of individual white families is to blame for the sinking levels of black-white exposure in school.

It’s undeniable that a shrinking percentage of black students attend schools with substantial numbers of white students. But some commentators, such as the conservative journalist Robert VerBruggen, have argued that the trend is attributable to demographics rather than policy choices.

In an article last year for the National Review that attracted controversy, VerBruggen wrote that the slow-motion transformation of white students into a minority group has led to fewer schools with significant white populations, and therefore fewer chances for minority students to encounter them in schools. In other words, you can’t bring minority students into white-dominated schools that simply don’t exist.

University of Arizona sociologist Jeremy Fiel has come to a similar conclusion. In a series of research papers investigating the racial composition of American schools, he has found that, while levels of segregation are indeed high, they likely don’t result from decisions made by families or school districts.

“The trend in terms of inter-group exposure is mostly due to the fact that whites are a declining share of the student population overall, mainly because there are more Hispanic and Asian students than there were in the past,” he said. “It’s not because the processes where people sort across schools have changed such that they avoid people of different ethnic groups. Really, it’s a story of changes in the composition in population.”

To John Brittain, dean of the University of the District of Columbia’s David A. Clarke School of Law, those claims ring hollow. A prominent civil rights attorney who has filed briefs in school integration cases before the Supreme Court, he said in an interview that, beginning in the 1991 case Board of Education of Oklahoma City Schools v. Dowell, districts began to wriggle out of desegregation mandates by advancing the same argument.

“This term ‘demographics’ is the key that locked the door to … desegregating schools through the courts,” he said. “School districts petitioned the courts to end [desegregation] orders if they could show that the current segregation was the result of changing demographics — that it was just where people happened to live. And it was so natural, so unintentional, so voluntary that the schools were segregated, by ‘demographics.’ And the officials don’t really dig into what produces segregation, what produces ghettos, what are these so-called non-intentional acts that lead to predictable results.”

Looking forward, Brittain struck a pessimistic posture on future integration efforts. With a firm conservative majority on the Supreme Court, he observed, future legal challenges to segregated schools will face an uphill battle. Though neighborhoods are integrating faster than their schools, he noted, many are still divided along sharp color lines; the inevitable result is divided students.

“It is a fact that there’s more segregation today than in the 1960s, and it’s de facto segregation that is the plague in the United States,” Brittain said. “And it’s a fact that the number one cause of school segregation is housing segregation. Housing is segregated for the most part.”

Indeed, estimates from the Urban Institute indicate that roughly 76 percent of the variation in school segregation between cities can be attributed to neighborhood segregation.

PDK’s Starr agreed that more must be done to decouple housing patterns from school assignments. The natural solution — busing students across school districts, which generated enormous contention in the 1970s — is gravely flawed, he said.

“You just don’t want to bus kids too far. It’s not only expensive, it’s disruptive. I feel like that’s sort of a cop-out statement, but it’s the truth.”

Not only that, busing is still very unpopular. In PDK’s 2017 poll of school parents, large majorities of respondents said that they would rather send their children to schools that were closer, but less diverse, than those that were farther away. By a 52-40 margin, even non-white parents reached that conclusion.

Looking ahead, Fiel of the University of Arizona said that even as American communities become more diverse, he wouldn’t bet on classrooms going in the same direction. Government interventions were too fraught, he said, and rapidly proliferating school choice options have complicated matters further. The world that Brown v. Board created may still be one that leans against integration.

“There isn’t going to be a top-down effort to desegregate schools,” he said. “And honestly, looking back, it’s really amazing it happened for even a short period of time.”

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.