by Chris Warshaw, Matt Barreto, Matthew A. Baum, Bryce J. Dietrich, Rebecca Goldstein and Maya Sen

The Trump administration’s attempt to add a citizenship question to the 2020 Census reaches the Supreme Court on Tuesday. Thus far, three federal judges have ruled against the Trump administration, most recently in Maryland. The Supreme Court will consider not only whether the administration violated administrative law, but also whether its attempt violated the Constitution.

A crucial issue in the case is whether adding this question for the first time since 1950 will hurt the ability of the census to accurately count the American population. In particular, critics of the administration fear the question will dissuade some U.S. residents, especially immigrants, from answering the census.

Research suggests these fears are justified. Working separately, we have used surveys and experiments to show that the citizenship question would make people less likely to respond to the census and provide complete information if they do respond. This is particularly true for Latinos and immigrants.

Latinos and immigrants fear citizenship information wouldn’t be protected.

The first piece of evidence comes from a survey conducted by UCLA political scientist Matt Barreto from July 10 to Aug. 10. It included a random sample of about 6,300 adults, including oversamples in California, the city of San Jose and two predominantly Latino counties in Texas, Cameron and Hidalgo. This provided a larger sample of Latinos (roughly 2,300) and immigrants more generally. More details about the survey and its methodology, as well as a full description of the survey’s findings, are here.

The survey revealed profound distrust about whether any citizenship information in the census would be kept private. Nationally, only 35 percent of immigrants and 31 percent of Latinos trusted the Trump administration to protect this information and not share it with other federal agencies — an issue that has already arisen in debates about the citizenship question. Trust in the Trump administration was even lower in California and San Jose. Substantial percentages of immigrants (41 percent) and Latinos (40 percent) are specifically concerned their citizenship information will be shared with Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

It’s no wonder then that notable percentages also reported that they would not respond to the census if it included a citizenship question. This included 7 to 10 percent nationally (taking into account uncertainty in the survey estimates), 11 to 18 percent of immigrants and 14 to 17 percent of Latinos. These percentages were even higher among those with larger households, which would further exacerbate any undercount.

A citizenship question experiment lowered willingness to respond to the census.

The second piece of evidence comes from an experiment embedded in these surveys. All respondents were asked whether they would complete the census, but a random half of respondents were told that it would include a citizenship question.

Barreto and George Washington University political scientist Chris Warshaw found that respondents told about a citizenship question were less likely to say they would take the census. The citizenship question caused a drop of more than two percentage points among all respondents. It caused six-point drop among Latinos and an 11-point drop among those who are foreign born.

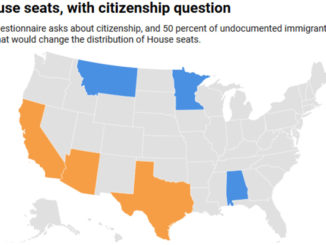

Warshaw’s analysis suggests that this would lead to substantial undercounts in states with large immigrant populations. For example, California could have an undercount of 2 to 4 percent — or approximately 1 million people. These undercounts could affect the apportionment of congressional seats. California would probably lose a seat, and other states with large immigrant populations, such as New York and Texas, could lose seats as well.

The same would happen for some counties and cities. Including a citizenship question would probably reduce the voting power of urban counties and increase the voting power of rural counties. It would probably reduce the voting power of New York City, Miami, Providence, R.I., and other large cities with substantial immigrant populations.

Adding a citizenship question would hurt the quality of information that Americans provide.

The third piece of evidence comes from an experiment embedded in a survey of more than 9,000 Americans, including an oversample of almost 5,000 Latinos. The survey was conducted from October through November by Harvard political scientists Matthew A. Baum, Bryce J. Dietrich, Maya Sen and Rebecca Goldstein.

The survey mimicked the census short-form questionnaire and included an experiment in which half of respondents received a questionnaire with a citizenship question and half did not.

The Harvard researchers found the citizenship question negatively affected people’s willingness to complete the survey. Overall, Latinos skipped 4 percent more questions when they received the citizenship question. Latinos born in Mexico or Central America skipped 11 percent more questions.

Receiving the citizenship question also made Latinos less likely to provide information about their household members’ race or ethnicity and led them to report fewer household members as having Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin. Latinos who received the citizenship question underreported Latino household members by six percentage points.

The Harvard researchers estimate that asking about citizenship would reduce the number of Latinos reported in the 2020 Census by approximately 6 million, or around 12 percent of the Latino population, based on 2010 figures.

None of this should be surprising.

What’s remarkable about the citizenship-question controversy is that none of this should be news to the Trump administration. After all, internal census analyses have already estimated that the citizenship question could decrease response rates among noncitizens by nearly 6 percent.

This evidence deserves to be front and center as the Supreme Court considers the possibility of adding a citizenship question. If the Trump administration’s decision is upheld, our research suggests, it would severely affect the ability of the Census Bureau to gather accurate information about the American population.

Chris Warshaw is an assistant professor of political science at George Washington University.

Matt Barreto is a professor of political science and Chicana/o studies at UCLA and co-founder of the research and polling firm Latino Decisions.

Matthew A. Baum is a Marvin Kalb Professor of Global Communications at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Bryce J. Dietrich is a research fellow at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and an assistant professor of social science informatics at the University of Iowa.

Rebecca Goldstein is a PhD candidate in the department of government at Harvard University.

Maya Sen is an associate professor of public policy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.