by

Erie, Pennsylvania, has a population problem: Once a metropolis of almost 140,000, it has dropped below 100,000.

But Erie’s situation would be even worse without the stream of immigrants and refugees arriving to work in the city’s plastics and biofuels plants on Lake Erie. Without refugees and their children, the city’s population might have dropped as low as 80,000, said Renee Lamis, chief of staff for Democratic Mayor Joe Schember.

“That would mean a lot less federal funding, a lot less tax dollars, a lot more difficulty filling job openings and a lot more deteriorating housing stock,” Lamis said.

“We are a perfect example of a place in need of immigrants and refugees,” she added.

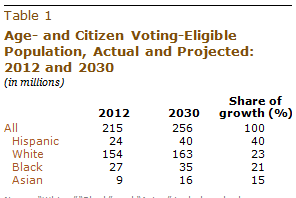

An influx of immigrants prevented or significantly softened population loss last year in more than 1 in 5 U.S. counties, including the one where Erie is located, according to a Stateline analysis of new census figures. Immigration either prevented population decline or cut it by at least 10% in those areas.

In recent years, even some big cities that have been magnets for young people have experienced population loss or slower growth, in large part because of escalating housing costs.

But in more than half of the largest urban counties, defined by the National Center for Health Statistics as part of a central city of a million or more, immigration stopped or significantly lessened population loss, according to the analysis.

‘Hundreds of Job Openings’

Earlier this month, President Donald Trump repeated his assertion that the United States is “full” and shouldn’t accept any more immigrants. But many cities and small towns across the United States desperately want more immigrants to fill jobs and keep their populations from shrinking.

Without the 879 people who arrived from other countries between 2017 and 2018, Erie County’s population loss — 1,831 people — would have been almost 50% worse.

As they have nationwide, refugee arrivals have slowed in Erie under the Trump administration. More than a thousand people from Somalia, Syria and the Congo were resettled in the city in 2015 and 2016, but that number dropped to fewer than 250 in the past two years, according to federal resettlement statistics.

“We have literally hundreds of job openings, and our landlords have vacancies,” Lamis said. The city had to raise income taxes and raid reserve funds to make ends meet.

In many cases, the desire for more immigration cuts across the country’s political boundaries.

In solid-blue Wayne County, Michigan, the city of Detroit is trying to lure refugees from nearby Dearborn to help resettle the neighborhood of Warrendale, where vacant housing is still a major problem a decade after the housing bust.

“It would mean fewer vacant homes and more customers for local business,” said Frank Nemecek, a 49-year-old insurance agent who lives in the Warrendale house where he grew up. Ten years ago, at the height of the housing bust, almost 1,000 of the 9,000 homes in the neighborhood were vacant, he estimated, and crime soared.

“The majority of residents are at least amenable to the idea,” Nemecek said. “The one big caveat is that a lot of residents and business owners worry about doing anything that would bring the wrath of the White House upon us. Many people simply feel that Detroit has enough problems. We don’t need to add a pissed-off president to the list.”

Republican-dominated Kandiyohi County in Minnesota, west of Minneapolis, also wants more immigrants. The city of Willmar in Kandiyohi County has come to depend on refugees and other immigrants to help raise and process turkeys.

The annual settlement of Somali refugees dropped from 30 in 2016 to just four in 2018, though the city already has more than 3,000 immigrants living there, mostly from Africa and Latin America.

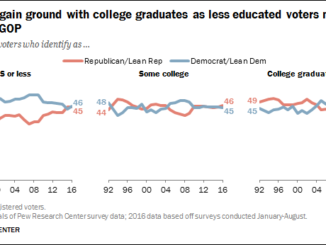

Nevertheless, there are hints that not all longtime residents are happy about the newcomers streaming in. In Erie County and Winona County, Minnesota, for example, an increase in immigrants coincided with a right turn by voters: Both counties voted Republican in 2016 for the first time in decades.

Fewer Refugees

The Trump administration’s drive to reduce refugee resettlement in the United States is being felt in many places that want more workers. Refugee arrivals in the United States dropped from about 79,000 in 2016 to 17,000 last year, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

“There’s no relation between the capacity of the United States to host refugees and the number who are arriving. The capacity is much higher,” said Stacie Blake, director of government relations for the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, a Virginia-based nongovernmental organization that coordinates refugee resettlement.

More than a third of local resettlement offices had to close or suspend operations because of the sharp decrease in refugees, Blake said, including one in Rutland, Vermont, a small town that once hoped to stem population loss with Syrian refugees. Rutland County lost 328 people last year despite 31 new immigrants.

Housing vacancies are up, and resettlement agencies have downsized in Clarkston, Georgia, a small town of fewer than 13,000 people where refugees, including many Syrians, began settling several years ago.

Many commuted by van or bus for hours to reach poultry plants outside Clarkston, Democratic Mayor Ted Terry said. Now some of the earlier arrivals have decamped for other places, and no new refugees have come to replace them.

Trouble in Minnesota

The Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration and its desire to reduce the number of refugees settling here has had a huge impact in Minnesota, said Todd Graham, a principal forecaster for the Minneapolis-Saint Paul Metropolitan Council who sits on the committee of the U.S. Census Bureau’s State Data Center Network.

“This is not surprising,” Graham said. “Immigration is greatly shaped by policies and their implementation. The Trump administration has changed things.”

Minnesota’s Winona County has lost about 600 people since 2010, but immigration has cushioned the loss.

Most of the newcomers are Hispanic immigrants who work in dairy farms in the rural areas outside Winona, rather than in the city where factories on the Mississippi River make flour, tire chains and medical devices.

Those factories are desperate for more workers, said Della Schmidt, president of the Winona Area Chamber of Commerce.

“The immigrant people are important, even critical, to agriculture here,” Schmidt said. “Unfortunately, we have not seen that cross over into manufacturing.”

The factory jobs require more technical skills and English fluency. One factory is planning to bring Hmong refugees from La Crosse, Wisconsin, 30 miles down the river, to fill jobs in Winona County.

In Kandiyohi County, Willmar Mayor Marv Calvin said he wants to see more jobs go to natives like him, but that “without immigration, we would not be able to meet our workforce needs.”

Nearly 200 new immigrants arrived in Kandiyohi County between 2017 and 2018, increasing the population by 140. As recently as 2011, the population decreased by 35 people.

“Local folks do not wish to do these tasks,” Calvin said. “Our local youth leave the area to attend school and then do not return home.”

Read more Stateline coverage of the 2020 census.

Tim Henderson covers demographics for the Pew’s Stateline.