by Richard Whitmire

This article was originally published at The 74.

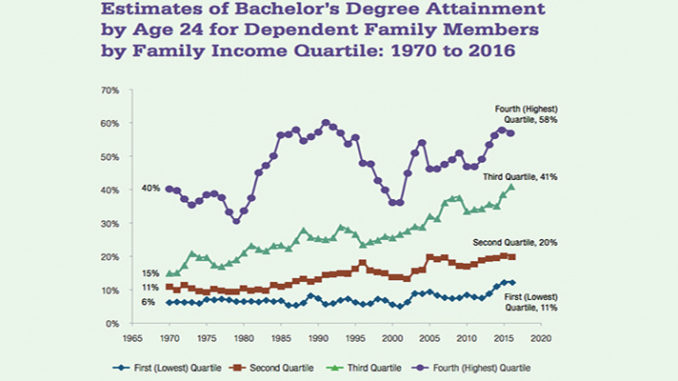

America’s higher education problem is not a college enrollment problem. The percentage of students who head straight to college after high school has risen from 63 percent in 2000 to 70 percent in 2016, according to the Department of Education. What we have is a graduation problem, especially among low-income minority students: Just 11 percent of students from the lowest-income quartile earn bachelor’s degrees within six years (the commonly used indicator of college success), compared with 58 percent of students who come from the highest-income group, according to the Pell Institute.

The National Center for Education Statistics tracked a 2002 cohort of U.S. students, finding that only 14.6 percent of those whose families are in the lowest-income quartile earned bachelor’s degrees within 10 years, compared with 46 percent from the highest-income group.

“Just 14 percent of black adults and 11 percent of Hispanic adults hold bachelor’s degrees, compared with 24 percent of whites.”

The astonishingly low college success rates alarm many liberal-leaning groups, such as the Education Trust, but also worry conservatives, who note that the problem is not limited to low-income students. Rick Hess, director of education policy studies at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, led a team that examined the dilemma. Writes Hess: “In 2016, more than 40 percent of all students who started at a four-year college six years earlier had not earned a degree … This means that nearly two million students who begin college each year will drop out before earning a diploma … There are more than 600 four-year colleges where less than a third of students will graduate within six years of arriving on campus.”

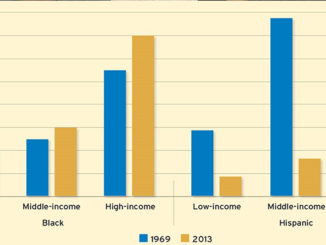

But the issue is most acute among blacks and Hispanics, where the college enrollment rates keep rising but the success rates — those who actually walk away with four-year degrees — are barely better than flat. They drop out before earning degrees. The overall college graduation figures reveal the imbalance. Just 14 percent of black adults and 11 percent of Hispanic adults hold bachelor’s degrees, compared with 24 percent of whites.

Overall, about a third of the students who enroll in college still haven’t earned a bachelor’s degree at the six-year mark, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. Not surprisingly, the dropout rates are higher for first-generation students. A third of first-generation students drop out of college at the three-year mark, compared with a quarter of students whose parents have degrees, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Various government agencies and advocacy organizations have different ways of cutting and framing the data, so the rates are going to appear slightly different, depending on the report. But one thing never changes: the significant completion gaps by race and income.

Among Hispanics ages 25-34, just 17.8 percent have a bachelor’s degree, compared with 43.7 percent of young white adults. Roughly half of Hispanic students who start at four-year colleges as first-time, full-time students earn a bachelor’s degree from those institutions, a rate 10 percentage points below whites

For black students, the college success gaps are even starker. Forty-one percent who enrolled in four-year colleges as first-time, full-time students earned degrees there, which is 22 percentage points below white students. Especially troubling is the lack of intergenerational improvement among black adults. Only 30 percent of younger blacks, ages 25-34, have earned a degree, compared with 27 percent of older black adults, ages 55-64. Now compare that to whites, among whom young adults today earn college degrees at a rate 10 percentage points higher than older whites.

For black and Hispanic college students, where you go matters most

Although colleges and universities have been improving their overall graduation rates, that doesn’t mean all students are benefiting. Among colleges that improved their graduation rates from 2003 to 2013, more than half didn’t make the same gains for their black students, according to the Education Trust. More ominously, at about a third of the colleges and universities in that study, the graduation rates for black students either flattened or declined. The states with the highest degree attainment for black students: Georgia, Maryland, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Virginia. The lowest: Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin.

We know that both black and Hispanic students take the most remediation courses in college, which greatly increases their odds of dropping out. For poor students, no-credit classes that cost money are non-starters. About 70 percent of black community college students end up in remedial courses, and almost half of those enrolled at non-flagship four-year institutions do. Many of those students have to take remedial courses in both English and math. Concludes Complete College America: “Forty percent of African American students and 30 percent of Latino students and 32 percent of Pell students at community colleges are enrolled in both remedial math and English. As a result, these students have, at a minimum, two additional courses they must enroll in, complete and pay for as part of their postsecondary education … It is easy to understand how placement in remedial education could negatively impact efforts to boost completion rates among students of color and low-income students.”

Here’s one certainty we know about Hispanic and black students: where they enroll in college makes the biggest difference. The Education Trust, which documents college success differences as part of its CollegeResults.org tracker, offers this example: At Whittier College in California, Hispanic students graduate at a rate 5.5 percentage points higher than white students. By comparison, at Mercy College in New York, white students graduate at a rate that is 22 percentage points higher than Hispanics.

For black students, the lesson is similar: Where you go matters most. The Education Trust offers this example: At the University of California, Riverside, 67 percent of black students earn bachelor’s degrees within six years, compared with 44 percent at the University of Illinois at Chicago. At Middle Tennessee State University, the black graduation rate is 40 percent, compared with 20 percent at Eastern Michigan University. At California State University, Fullerton, the black graduation rate is 56 percent, compared with a rate of 39 percent at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Nationally, the graduation rate for Pell students — low-income students qualifying for federal grants — is 51 percent, compared with 65 percent for non-Pell students. When the Education Trust scrubbed the numbers for 1,100 public and private institutions, it found something compelling: Half of that graduation gap can be explained by Pell students enrolling in institutions with low college success rates. In short: Poor college counseling plays a significant role here. “By closing existing gaps at the college level, especially the egregiously large gaps that exist in about one third of four-year institutions, we can cut that gap in half,” writes report author Andrew Nichols.

So-called summer melt — the phenomenon by which students who were accepted to college and planned to attend don’t show up for classes in the fall — contributes heavily to the gap, at an estimated 20 percent. And for low-income students, that rate doubles, says Melissa Fries, executive director of CAP, a California nonprofit that helps low-income students earn degrees. One reason she cites for the significant summer melt among poor students is the startling high ratio of students to guidance counselors. In some high schools, a counselor can have caseloads of up to 900 students.

“Even if caseloads are reasonable, many counselors don’t work during the summer, when a myriad of tasks need to be completed: submitting final transcripts, taking placement tests, signing up for housing, verifying financial aid information, and logging into their institution’s online portal to register for orientation and complete other tasks,” writes Fries. “Often, parents can’t help either. Many juggle multiple jobs and are not native English speakers, and some don’t know how to use a computer. For the most part, they haven’t attended college themselves and can’t navigate the complicated registration system.”

College completion a black box for high schools

High school principals have never shown much interest in the college success rates of their alumni. They have enough on their plates just getting their students to earn high school diplomas. College success? Isn’t that up to the alumni, their parents, and the colleges? Even if those high school leaders suddenly turned curious, they would have little data to draw from. Only two states, Georgia and Michigan, make available full data on whether graduates from specific high schools end up with college degrees, according to a 2018 report from the nonprofit GreatSchools.

So Georgia and Michigan have turned the corner? Not exactly. In reality, anyone seeking that data will experience what I discovered when I tried to test the system by searching for college success information for a sampling of high schools located in both high- and low-income neighborhoods. On my own, I never found the right website. Finally, I tracked down the data expert in the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement in Georgia, who led me to the relevant data dashboard. Even then, I struggled to complete what should have been a simple comparison of rich and poor schools.

If I had trouble, even with the state expert on the phone, what do parents from Georgia experience? As it turns out, that’s not a problem, mostly because parents don’t even realize the data is there, said Michael O’Sullivan, executive director of GeorgiaCAN, a school reform advocacy group. High schools don’t make it available on their report cards. O’Sullivan said his group uses the data in presentations to parents, but generally, “it’s not really out there.”

There may be a reason why superintendents and principals don’t like to share that data: It disrupts their narrative to parents that their districts and schools are wonderfully successful because their alumni go off to college. When Nicole Hurd’s team from the College Advising Corps arrives at a school to pitch their college advising services, they come prepared with college success data culled from the National Student Clearinghouse. For a fee, the Clearinghouse will match high school graduation records against college records to determine who enrolled in college, who persisted, and who ended up earning degrees. Before sitting down with high school leaders, Hurd’s team collects college graduation data.

Only rarely do we get a glimpse into any accurate college success rates for the big urban school districts, and that data doesn’t usually come from the district itself

The most awkward conversation I’ve had, and the most heartbreaking, has been determining baseline data as we begin to partner with a school,” said Hurd. “Ideally, we are able to collect [National Student Clearinghouse] data for three years to establish a baseline and then measure impact. A couple of times, I’ve had the awkward situation of sharing with a principal or team of educators the NSC data for the first time and it was lower than what they anticipated.”

Hurd continues: “Unfortunately, schools often use self-reported data. For example, there may be an at end-of-the-year survey where they say ‘How many of our students are going to college?’ And the students raise their hands and then the school may record as many as 90 percent of their students are going to college. But then you run the NSC data and it may be as low as 50 percent who actually enrolled, and they look stunned. As much as this is an extremely tough moment, our message has been, ‘We are not here to judge, we want to work with you and hold hands with you, and we’re not going to know if we’re being effective without baseline data.’ But for a number of schools, establishing a baseline is a shocking moment.”

Only rarely do we get a glimpse into any accurate college success rates for the big urban school districts, and that data doesn’t usually come from the district itself. In late July 2018, we got a look at Newark Public Schools data, thanks to a report from the Newark City of Learning Collaborative and Rutgers University–Newark’s School of Public Affairs and Administration that tracked 13,500 students who graduated from high school between 2011 and 2016. The headline from the press coverage: “More Newark students are going to college, but only one in four earns degree within six years, new report finds.”

There was good news in the press report: About half of Newark Public Schools students who graduated from high school between 2011 and 2016 went directly to college, compared with 39 percent of graduates from 2004 to 2010 who did that. And six years after leaving high school, 23 percent of the Class of 2011 had earned a college degree or certificate — more than double the rate of the Class of 2006. Sounds promising, but an online data supplement allowed an apples-to-apples national comparison with low-income students across the country who earned four-year degrees (not counting professional school certificates or two-year degrees). Among Newark’s graduates who went to traditional comprehensive high schools, only 7.2 percent earned bachelor’s degrees, compared with about 11 percent of low-income students nationally. Not surprisingly, those who went to a Newark magnet school fared better, with 33 percent earning four-year degrees. For the KIPP students in Newark, 31 percent earned degrees. Based on comparable studies in cities such as Chicago, there’s reason to assume that similarly bad news would emerge from most urban districts, such as Los Angeles or Detroit or St. Louis.

College: Overrated or still the best shot at escaping poverty?

Critics of the push to raise college success rates among low-income, minority, and first-generation students have an easy answer to these low success numbers: Why bother? College is overrated, likely to trigger punishing debts, and unlikely to produce jobs any better than skilled tradesmen. The country needs more plumbers, electricians, and welders, they argue.

The “college or bust” attitude of most education reformers is misplaced, argues Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank. “A better approach for many young people would be to develop coherent pathways beginning in high school, into authentic technical education options at the postsecondary level. But, right now, 81 percent of high school students are taking an academic route; only 19 percent are “concentrating” in career and technical education.”

One quick glance at the dismal college success rates for low-income students should be enough to convince everyone that the college-for-all approach is not only misguided — it’s not working, say the critics. Boosting trade schools and apprenticeships, not promoting bachelor’s degrees, makes more sense for both the students and the country, they argue. The critics have a point; there are some quality vocational education programs, especially those done with business partners. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos embraces it as well, saying that the incessant push for four-year degrees overlooks trade schools. “To a large extent, we have stigmatized them for the past couple of decades. We have a lot of students who would benefit from being exposed to those different options.” And Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta agrees.

Of course, the biggest “offenders” in the eyes of these critics are the charter school leaders, who even in the early grades pitch their schools to parents and teachers as their best bets for earning college degrees. We will pull your next generation out of poverty, they imply. Walk through any of the top charter elementary schools, and you’ll see the college banners of the schools where the teachers earned their degrees. In some schools, the entire class gets nicknamed for the alma mater: Here’s the “Amherst” class!

The charter leaders respond in two ways. The first answer, calm and pragmatic, is that yes, trades should be promoted. And some charters, including the Rooted School in New Orleans, are showing how that’s done. But trade schools require literacy and math proficiency levels that in poor neighborhoods are best achieved by delivering a college preparation curriculum, they say.

TA college degree is the most reliable way we know of to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty — Richard Barth, CEO KIPP Foundation

The second response gets delivered in a more seething tone: Are those same advocates directing that message toward their own children and their friends’ children? Why aren’t we hearing that same advice aimed at high school students from wealthy suburban neighborhoods or those attending expensive private schools? Why does it come up only when we’re talking about low-income, minority students? Don’t the students and their families deserve some say here?

Charter leaders such as KIPP’s Richard Barth are especially bothered by suggestions that charters should back away from their emphasis on earning college degrees. Barth wants KIPP to support students who choose non-college paths, but he says there are good reasons to emphasize college.

He writes: “A college degree is the most reliable way we know of to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty. With a four-year college degree, over 40 percent of young people born into the U.S.’s lowest income quintile make the jump into the top two quintiles of income. With only a high school diploma, just 14 percent of young people in the lowest national income quintile will rise into the two top quintiles. Young people understand the payoff: Of the two-thirds of college-educated millennials who borrowed money to pay for their schooling, 86 percent say their degrees have been worth it or expect that they will pay off in the future.”

My take on the trade-school-versus-college debate: The angry, visceral reaction you hear from charter leaders and other champions of the college path (“Are the critics steering their own children into the trades?”) obscures the good points being made by those critics. Of course, students should have good options for pursuing a career that doesn’t require a bachelor’s degree. The tough reality, however, is that many high schools, especially those in high- poverty areas, aren’t doing a good job preparing students for either a career or college.

In August 2018, those twin deficiencies got laid out in an Achieve report titled “Graduating Ready.” A majority of college instructors report that fewer than half of recent high school graduates are adequately prepared in math and reading. And 61 percent of employers report that they require recent high school graduates to obtain additional education or training.

Attempts by states to fix those twin readiness problems, called college-and- career-ready (CCR) tracks, produce very different results. In Indiana, for example, where the CCR coursework is considered the default and students must opt out, 89 percent of all graduates pursue that track, including 86 percent of black students and 85 percent of Hispanic students. By contrast, in California, where students must opt in, just 47 percent of all graduates, 36 percent of black students, and 39 percent of Hispanic students complete the more rigorous CCR coursework.

As I learned from researching my book Why Boys Fail, it makes sense for many low-income students to embrace a college track curriculum, regardless of their ambitions. That’s the only way they can acquire sufficient literacy skills to handle trade school training programs. Here’s a compromise to suggest for the quarreling camps: Starting with the charter networks (hopefully all high schools will join in eventually), begin citing three “success” outcomes for alumni: percent who earn professional certificates, percent who earn two-year degrees, and percent who earn bachelor’s degrees.

Finally, we know from polling that first-generation college-goers see college as their ticket to a better life. For good reasons. Who’s going to volunteer to tell them otherwise?

This is an excerpt from the new Richard Whitmire book The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. See more excerpts, profiles, commentaries, videos and additional data behind the book at The74Million.org/Breakthrough.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation funded a writing fellowship that helped produce The B.A. Breakthrough and provides financial support to The 74. The 74’s CEO, Stephen Cockrell, served as director of external support for the KIPP Foundation from 2015 to 2019. He played no part in the reporting or editing of this story.