by Alex Gonzalez

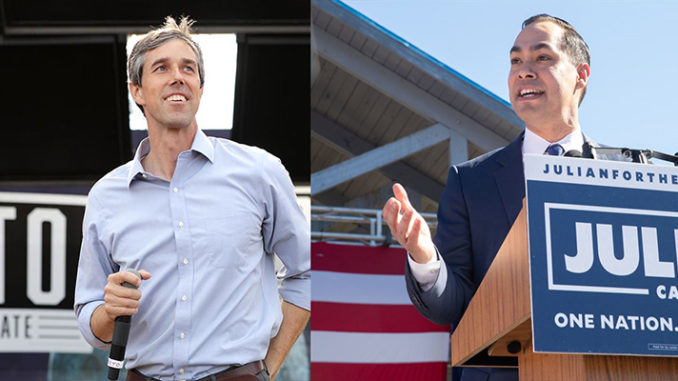

It’s no secret that Julian Castro and Beto O’Rourke are on collision course in Texas in their bid for the Presidency since both will be courting Hispanics in the Texas, and across Southwest, where most of these Hispanic voters are Mexican-American. So It’s worth diving into the “Mexican-ness” of Julian Castro and Beto O’Rourke as they seek to lure Mexican-American voters.

What I mean by “Mexican-ness” is the relation both Beto and Julian have with the Hispanic community in Texas, which happens to be mostly Mexican-American, and how they connect with the “Hispanic” community by explaining cultural affinities and policies that both Beto and Julian perceive are important to Mexican-American voters. Beto is not Mexican-American, but political identities and genetics are different; political identities don’t necessarily have to be genetics since they are cultural and culture is a learned behavior.

I’m going to use the first names only since both Beto and Julian sounds more casual than O’Rourke and Castro.

In the Texas U.S. Senate race against Ted Cruz, Beto was able to win more than 70% of the “Hispanic” vote in the state while some estimates suggest Cruz got only 22%. In fact, Beto did much better in wooing Mexican-American voters in Texas than Loretta Sanchez in California where she received only 53% of the Latino vote in 2016 while Kamala Harris got 47% in the US Senate race. Therefore, there is no doubt of what the “Beto effect” did, it succeeded in luring Mexican-Americans and young votes in Texas – 90% of all Hispanics in Texas are Mexican-American – from a “Latino” candidate, Ted Cruz, in a very red state. And, though, Julian is genetically Mexican-American, some question whether his ethnic identity alone is strong enough to lure “Latino” voters; moreover, Julian often seems unable, or unwilling, to explain his own Mexican-American identity, and this, perhaps, makes him vulnerable against someone from El Paso who cheerfully and openly talks about his love for Juarez and Mexico and the bi-national cultural and economic identity of El Paso and Juarez.

So let’s start with the obvious double standard for Mexican-Americans in the 2020 race.

Unlike Beto who has built a political career and image as a “border guy” who cheerfully jogs and bikes between Juarez and El Paso to display his love and solidarity with Mexico and Juarez, of course, to woo Mexican-American voters, Julian is hesitant to show his Mexican-American roots openly, and instead, he resorts to label such as Latino and “Latinx” to subtlety address his Mexican-American identity. But he has to. The fact is that Beto enjoys a sort “white privileges” that Julian wouldn’t be able to get away with without raising suspicion of being too “Mexican ” just because he is in fact Mexican-American; Beto has even said he’d take down the wall in El Paso, which made Trump angry, but that was the end of it.

Because of the last name O’Rourke, Beto goes between Juarez and El Paso speaking about fraternity, community and partnership with Mexico, and no one accuses him of being “too Mexican.” Even Republicans try to portray Beto as not Mexican enough by insisting in calling Beto “Robert;” Republicans in Texas are the only ones in the country who still think Mexican-American voters are dumb enough not to know why GOPers keep calling Beto “Robert.” The true is it would be harder for Julian to do what Beto does before Republicans directly accuse him of working for Mexico. So yes, there is double standard for Mexican-Americans, and Beto gets some type of “white privileges” just for being “O’Rourke.”

But whose fault it is that Julian can’t talk openly about being Mexican-American, and instead, has to resort to subtle coping mechanism using labels like “Latinx”?

About two months ago, Julian wrote an op-ed to explain why labels like “Latinx” makes sense to explain his “Latino” identity. He wrote:

As I sat in a computer room in my dorm working away on an early Macintosh, a red squiggly line immediately appeared underneath the word “Chicano” after I typed it into the paper I was writing about my family’s background. When I hit the spell check to see what the problem was, Microsoft Word had a suggestion: Chicago. “You don’t even exist,” popped into my head. Unfortunately, this wasn’t a new experience. Years earlier, in middle school, I’d been asked to fill out a form that included a question about my background. There were three options to choose from: black, white or other. “Well, I’m not black or white,” I remember thinking, pencil in hand, “but I don’t like the sound of ‘other.’” I left it blank.

Essentially, because Microsoft Word didnt recognize the word “Chicano,” Julian felt as though he didn’t exist, as if his identity didn’t exist. As a result, a name like “Latinx” makes sense since it “refers to individuals of Latin American heritage in an inclusive way,” he argues. However, “Latinx” is recent invention in young progressive Latino groups and only a very small segment of Mexican-Americans, less than 5%, call themselves Chicanos/as. So perhaps, if Julian had typed Mexican-American, his identity would have showed up in his MAC Word and all this cultural confusion would have been avoided.

Similarly, in an interview with NY Magazine, Julian explains why he and Joaquin, his brother, don’t Speak Spanish Fluently:

Q. One line of commentary that’s followed you around for ages is about how you’re not entirely fluent in Spanish. What have you made of that over the years? Do you think it comes from a misconception about how the language is used now?

Julian: Uh. Yeah. I think it says something about a lot of people asking the question that they don’t understand the reality of the Latino community in the United States. First of all, there are a tremendous number of Latinos in the United States that are bilingual, and also those that are English-dominant, and also Spanish-dominant. But, you know, my brother and I speak some Spanish. We’re just not completely fluent. It’s not 100 or zero. It’s also ironic because my grandmother and my mother grew up in a time when they were punished for speaking Spanish, and this country effectively was telling them, “You go learn English. Your Spanish isn’t good enough here.” So it’s very ironic and makes zero sense that now somehow a Latino would be told, “You’re not good enough because you don’t speak Spanish.”

In his answer, Julian makes it clear that he can’t please everyone. He argues that some people criticize Mexican-Americans ( he uses the label “Latino” when in fact the time when Julian grew up in Texas everyone was Mexican-American) because we don’t assimilate quick and don’t speak more English, and now some people tell you that you need to learn more because “your Spanish isn’t good enough.” His point is that “damned if you do, and damned if you don’t.” And, he is Right. Mexican-Americans don’t really have to speak Spanish to represent the interests of the Mexican-American communities in the Southwest, or other Latino groups in the country, who may be 4th and 5th generation in Texas and they themselves don’t speak Spanish. Furthermore, Julian recalls that “my mother grew up in a time when they were punished for speaking Spanish.” And that is more or less what his brother responded to remarks made by Tom Brokaw suggesting that “Hispanics need to assimilate more.”

Here is what Joaquin wrote about his experience in response to Tom Brokaw ignorant remarks about Hispanics.

.@tombrokaw, for a celebrated @NBCNews journalist who spent years chronicling American society you seem stunningly ignorant of the Hispanic community in this country. Unfortunate to see xenophobia pass for elevated political commentary @MeetThePress https://t.co/nKoLhjWdbk

— Joaquin Castro (@JoaquinCastrotx) January 27, 2019

“To give some context as to why this matters, in Texas into the 1950s (and perhaps after) Spanish was literally beaten out of children. At many schools if you spoke Spanish you were hit by a teacher — spanked with a ruler or paddle.

Parents became reluctant to pass down the Spanish language and kids came to associate it with notions of shame and inferiority. That’s one reason why I find it so ironic that often times Hispanics today are shamed if they don’t speak Spanish.Yet another irony is the fact that many who prefer getting rid of “hyphenated Americanism” refer even to second, third gen Hispanic Americans as “Mexicans” – rather than Americans. It’s as if no matter how long you’ve been in this country you’re not ever really an American.

Final: All of this (and more) leads to a kind of self-hatred. In the neighborhoods where I grew up kids used to deride each other as “wetbacks” or “mojados,” an ethnic slurs against Mexicans.”

Consequentially, it would appear that for both, Julian and Joaquin, Speaking Spanish and using the name “Mexicans” to self-identify still brings memories of harsh treatment of Mexican-Americans in Texas, and thus, finding more generic terms like Latino or “Latinx” would make it easier to connect with more Latinos. Thus, part of Julian hesitation about his Mexican-American identity comes from the harsh treatment some Mexican-Americans in Texas experienced when he was growing up, so a more generic label would be more apt.

Consequentially, it would appear that for both, Julian and Joaquin, Speaking Spanish and using the name “Mexicans” to self-identify still brings memories of harsh treatment of Mexican-Americans in Texas, and thus, finding more generic terms like Latino or “Latinx” would make it easier to connect with more Latinos. Thus, part of Julian hesitation about his Mexican-American identity comes from the harsh treatment some Mexican-Americans in Texas experienced when he was growing up, so a more generic label would be more apt.

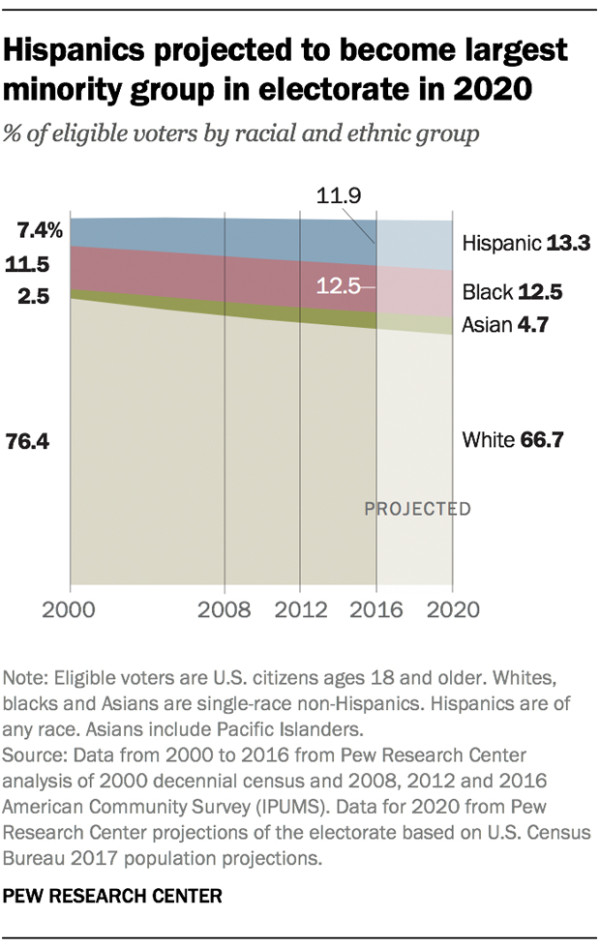

However, of 40 million of Mexican-Americans in the US, and the estimated 31-32 million Hispanics who will be eligible to vote in 2020, 80% are Mexican-Americans and 95% don’t call themselves Chicanos, nor “Latinx.” Additionally, historically, in politics, it is only when Diaspora groups use their identity to build political power that thy are successful in making real policy changes for their communities. What could be the source of strength for Julian to build a stronger political base among Mexican-Americans, he sees it as a liability.

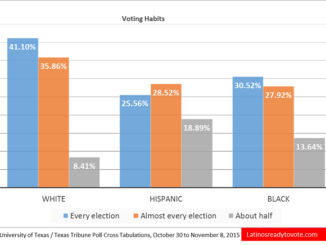

So the problem for Julian is not that he is Mexican-American, or that he doesn’t speak Spanish, his real problem is that he doesn’t assert his Mexican-American identity as a native culture of US, and instead, he resorts to “invented” ethnic labels as coping mechanisms to avoid telling the Mexican-American experience in the Southwest. Moreover, no evidence exist to suggest that Mexican-Americas in the southwest really connects with labels like “Latinos,” or he newly invented “Latinx.” Similarly, no data exits showing that “Latino” is a label favored among Mexican-Americans or that lead to high turnout.

And it is possible that because Julian wants to be too progressive in using a name like Latinx, or people of color – names that are popular among progressives to label all Hispanics/Latinos – Beto may “out-Mexican” Julian among Mexican-Americans in Texas and the Southwest who are more traditional and not as progressive as ‘Latinos” in the East coast.

Conversely, Beto can makes the argument that he has close views with Hispanics on policies, and culture; Beto can easily argue that his policy views on Immigration, border security, free trade, and NAFTA do reflect the views of most Hispanic/Mexican-Americans in Texas and the Southwest since he grew among Mexican-Americans.

So, can Beto, whom some have described as a “Mexico-loving” hipster and libertarian, lure Mexican-American voters more than Julian? It all depends on how progressive Julian doesn’t wan to be and how well he can tell his Mexican-American story to make them feel proud, not ashamed. For Julian, in not being able to tell the Mexican-American experience, and trying to sound too progressive with labels like “Latinx,” he is missing out in connecting with larger group of “Latinos” – Mexican-Americans.

Why Mexican-Americans shy away from their Identity and History?

This is a very complex issue but worth analyzing because it affects a generation of Mexican-American who were punished as children in school for speaking Spanish, which led to Mexican-Americans feeling inferior and ashamed, as Joaquin noted.

Samuel Huntington argued that national identities are constructed by ideology; and Identity is an individual’s or group’s sense of the self. Benedict Anderson’s Imagine Communities also argues that Identities are imagining selves. They are what we think we are and what we want to be. People may inherit ethnic identity, and they can embrace it or reject it. Moreover, identities are defined by the self but they are also the product of interactions between the self and the others. How others perceive an individual or a group affect the self-definition of that individual or group.

National identity is an “invention” as Benedict Anderson argues in Imagined Communities, or “constructed” as Huntington argues—and often they are mere bureaucratic procedures. So Individuals have a natural tendency to seek spiritual or ethnic connection with those with whom they share similar ancestral roots. Thus, nation-ness, like cultural identities, are cultural artifacts that used to be invented by kings, and now are invented by governments through an national myths, similar “group experience” or ideology, or by religious leaders as it the case of the Jews; so identity is the voluntary individual’s desire wanting to be part of something bigger.

But death brings individuals to face with central problems posed by ethnic identity because a idividauls cannot live forever, but a cultural identity can live forever under a romantic version of a country or nationalism. A man’s death is usually arbitrary, his mortality is inescapable. So for centuries religion was concerned with the idea of man-in-the-cosmos, and the contingencies of life; and man’s harsh reality of life. Thus, religion responds to this harsh terrestrial reality by transforming fatality into continuity (karma, original sin etc..). And cultural ethnic identities do the same in the form of nationalism or Diaspora; and as Anderson believed, “In this, way religion is concerned with dead and the yet unborn, and continuity in the cosmos;” and ethnic identities, whether nationalistic or Diasporic, operate the same way; individuals want to be part of something bigger than their mortality. Thus, appreciation for one’s ancestral ethnicity is also an spiritual idea that requires continuity in the afterlife. Religious ideas, then, after dead is what connects an individuals with ethnic ancestral identity because religion offers the means.

What Julian and Joaquin argued is that there is/was a generational shaming for Mexican-Americans, this leads to some Mexican-Americans no wanting talk or show their Mexican-American identity (Mexican-ness), and thus, their identity still lacks the cultural confidence to comfortably assert it and push back any suspicion of “double loyalties.”

Mexican-Americans are the only ethnic group with a legitimate historical emotional attachment to the southwest. Yet they were forced to reject their identity, as Joaquin wrote, so as to prove their patriotism; this also happens in so-called “conservative” circles. However, because one’s identity also depends on how others perceive you, even if Mexican-Americans don’t want to be perceived as Mexicans, they are already perceived as Mexicans by the others because that is what prompted other to ask them not to be too Mexican. So denying that you are Mexican-American could also be perceived as a sign of weakness and shame more than “patriotism.”

Unfortunately, Mexican-Americans in the U.S. still lack the cultural confidence, in politics, to confidently assert their identity and push back any suspicion of double loyalties, and that is why Julian has problems calling himself Mexican-American and shifts to “Latino” or “Latinx.” Yet, even Samuel Huntington agreed that Mexican-Americans are the only ethic group with legitimate historical emotional attachment to the Southwest. Yet often they are forced to reject their identity so as to prove their patriotism. However, as in Huntington’s argument about identity, because one’s identity also depends how others perceive you, even if Mexican-Americans don’t want to be perceived as Mexicans, they are already perceived as Mexicans by the others because that is what prompted other to asked them not to be too Mexican.

Thus, when Mexican-Americans denouncing their Mexican-ness –for an alleged patriotism– are denouncing their own “self” because their identity is not only conditioned by how they see themselves but also by how others perceive them. And, they will be perceived as Mexican even after they denounce it because, according the Huntington, how others perceive an individual or a group affect the self-definition of that individual or group. So the more they denounce it, the weaker and more fractured their identity becomes since one can never change—physically–his ancestral ethnic identity. But more importantly, when Mexican-American denounce their identity, they forgo their 150-years claims to this country and 300-years of Mexican culture and history in the Southwest. Essentially, they are forfeiting their ethnic confidence that comes from the history of being part of the nation before the Southwest part of the U.S. And this is why labels like “Latinx” confuses Mexican-Americans and it weakens their Mexican-American identity.

Thus, when Mexican-Americans denouncing their Mexican-ness –for an alleged patriotism– are denouncing their own “self” because their identity is not only conditioned by how they see themselves but also by how others perceive them. And, they will be perceived as Mexican even after they denounce it because, according the Huntington, how others perceive an individual or a group affect the self-definition of that individual or group. So the more they denounce it, the weaker and more fractured their identity becomes since one can never change—physically–his ancestral ethnic identity. But more importantly, when Mexican-American denounce their identity, they forgo their 150-years claims to this country and 300-years of Mexican culture and history in the Southwest. Essentially, they are forfeiting their ethnic confidence that comes from the history of being part of the nation before the Southwest part of the U.S. And this is why labels like “Latinx” confuses Mexican-Americans and it weakens their Mexican-American identity.

Huntington believed that identities are constructed by ideology and a cultural identity is an individual’s or group’s sense of the self, or it is product of self-consciousness—wanting to be part of a group. But Anderson believes that ethnicity is a spiritual connection with those whom we share similar ancestral roots (historical or religious). Groups become confident culturally, politically cohesive when they learn from the past.

Therefore, Mexican-Americans, as citizens of the United States, who object to their ancestral history as Mexicans, are limiting their future to their short mortality because they have been told to abandon their history as a group. But because they have abandoned their past Mexican-ness, they cannot have fraternal future since they have no cultural foundation for any historical claims to the Southwest.

It is difficult to foresee how many generations still it will take for Mexican-Americans to feel free of cultural inhibition to gain enough confidence to embrace their identity and not have their identity challenges with suspicions of dual loyalism. What do Mexican-Americans have if they continue rejecting their past? They will have no historical or claims to this country.

Other have Mexican-American scholars have noticed that the experience of Mexican-American children like Julian and Joaquin did happen, it doesn’t necessarily leads to cultural “shame.” Tomas Jimenez of Stanford in his book Replenished Ethnicity: Mexican Americans argued that even though American society discriminated against the descendants of these early Mexican immigrants because of their ethnic origin, the children and grandchildren of these immigrants moved out of ethnically concentrated neighborhoods, joined the military, intermarried, and experienced socioeconomic Mobility and do not want to be called “minority’.

But Jimenez also points out that Mexican Americans everyday experiences reveal that their ethnic identity is connected to contemporary Mexican immigration in ways that make that identity simultaneously more beneficial and costly. Mexican immigrant replenishment provides the means by which Mexican Americans come to feel more positively attached to their ethnic roots. But it also provokes a predominating view of Mexicans as foreigners, making Mexican Americans seem like less a part of the U.S. mainstream than their social and economic integration. But if third and fourth generations of Mexican-Americans feel cautious about their Mexican identity because it may threat their middle-class status and assimilation, it means that other groups can use that against them to further suppress and prevent any cohesive Mexican-American identity.

But Jimenez also points out that Mexican Americans everyday experiences reveal that their ethnic identity is connected to contemporary Mexican immigration in ways that make that identity simultaneously more beneficial and costly. Mexican immigrant replenishment provides the means by which Mexican Americans come to feel more positively attached to their ethnic roots. But it also provokes a predominating view of Mexicans as foreigners, making Mexican Americans seem like less a part of the U.S. mainstream than their social and economic integration. But if third and fourth generations of Mexican-Americans feel cautious about their Mexican identity because it may threat their middle-class status and assimilation, it means that other groups can use that against them to further suppress and prevent any cohesive Mexican-American identity.

Conversely, if Mexican Americans, especially old elites in Texas and California and New Mexico in the southwest were to assert their historical regional identity, that would reinforce the notion that they are not “a foreign culture,” they could potentially drive millions of new Mexican-Americans to the polls. This marriage of the old and the new generations would create a more assertive political cultural force that can guarantee future regional voting bloc.

Ruben Navarrete is right . Julian “has one heck of a good story to tell,” but demographics is where Julian can find its path to the presidency. For Julian to be successful, he will need to energize millions of Mexican-Americans to the voting booths. But Beto has done it very successfully already in Texas, and he has defeated other Mexican-American Democrats in a district that is predominantly Mexican-American.

Alex Gonzalez is a political Analyst, Founder of Latino Public Policy Foundation (LPPF), and Political Director for Latinos Ready To Vote. Comments to [email protected] or @AlexGonzTXCA