by Bekah McNeel, The74

All but five of the 637 students at Gallegos Elementary in Brownsville Independent School District qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Many come from homes without plumbing. More than 50 percent have limited English language skills.

In most cases, numbers like that would spell disaster on state accountability tests, but at Gallegos, 91 percent passed their state math exams in 2018. In reading, the biggest challenge for non-native speakers, 85 percent passed.

In terms of poverty, Gallegos Elementary is not much worse off than other schools in Brownsville ISD. In the district as a whole, 96 percent of students meet the criteria for economic disadvantage — meaning their parents make less than $44,000 a year for a family of four. Brownsville frequently ranks among the poorest cities in the United States. In 2013 and 2016, it took the number one spot, according to Census Bureau data.

Such widespread poverty is an unfathomable scenario for many districts in Texas, and yet Brownsville ISD continues to outperform even some of its wealthier peers, earning accolades and recognition across the state and country. In the 2019 National Blue Ribbon Schools nominations, the district’s Putegnat Elementary was nominated as a “high achieving” school, and Hudson Elementary was nominated in the “closing the achievement-gap” category. Winners will be announced in September.

The border district’s success is due to what might be called a “yes, and…” approach to improvement. Every campus uses data-based interventions under the leadership of strong, proactive principals. Families and community members are deeply engaged in the schools, a by-product of social networks that are stable, even though they are poor. The district leverages its high poverty rates to bring more state and federal dollars into classrooms.

On top of that solid foundation, Brownsville ISD is always looking for ways to improve. It’s doing so amid the kind of board-superintendent strife that has stymied other districts. In spite of a strong track record of improving schools, the Brownsville ISD school board terminated the contract of Superintendent Esperanza Zendejas this month for reasons that remain unclear. The district did not respond to requests for comment and Zendejas could not be reached after her departure.

The termination ended a four-year streak of continuous improvement under Zendejas’s leadership. However, with strong administrative and campus buy-in, the reforms could well be permanent.

Brownsville has taken advantage of nearly every innovation program available through the Texas Education Agency, and it even successfully pushed for its own state legislation to fund new programs. Early college high schools, pre-kindergarten for 3-year-olds, and an elementary school choice program have given the district a lot to showcase, but the underlying strength of the district is more fundamental. In an interview in late October, Zendejas recounted that her strategy from day one rested on the shoulders of the system’s 57 principals.

Taking up the helm of Brownsville ISD in 2015 was a homecoming of sorts for Zendejas, as she first served in the role from 1992-1995. She had gone on to lead Indianapolis Public Schools and two districts in California. When she returned, she had definite ideas about how to improve the district.

Her first move was to demote campus principals whose accountability scores had languished over time. In their place, she appointed school leaders who could get the job done, bringing test scores up to passing and beyond. Needless to say, this was a controversial move. Brownsville is a tight-knit community, and what online rumor mills exist continued to criticize Zendejas’s “management style.”

The board placed Zendejas on administrative leave with pay on Jan. 11. Neither the board nor the district issued a statement on the initial actions, which came just months after Zendejas received a two-year contract extension and a raise in October. However, watchdogs and bloggers pointed to her oversight of a stadium vendor contract.

Zendejas alluded to retribution for the principal demotions and those on the board who wanted to see her gone when she spoke to The 74.

“If you want to make a difference, you have to take risks,” she said. “That can have fallout, but if it’s in the best interest of kids, who cares?”

Although her own contract was cut short, the district itself is pretty far down the pathway she set. In 2018, Brownsville ISD joined the state’s “System of Great Schools” initiative, which encourages campuses to function more autonomously, with the principals wielding significant power and the potential liability that accompanies it.

“You need the strongest principals to be able to capitalize on all the opportunities,” Zendejas said, “and to manage the challenges that poverty drops on your doorstep.”

Get them early

Brownsville, population 180,000, is both the southernmost city in Texas and the easternmost city on the U.S. border with Mexico. It is — even by Texas standards — an outpost, a four-hour drive from San Antonio, or a five-hour drive from Houston. When Brownsville ISD started rapidly improving on state accountability scores, legislators and educators alike began to notice, but because of the location, some of its success has remained a bit mysterious. Brownsville just doesn’t get many visitors, at least not like Dallas ISD or San Antonio ISD, both of which have become darlings of the Texas Legislature and the Texas Education Agency.

“It’s not a turnaround story. It’s a story of continuous improvement,” said Seth Rau, government and community relations coordinator for San Antonio ISD. “People love silver-bullet stories.”

In his role at the Texas capitol, Rau sees a lot of Dallas ISD Superintendent Michael Hinojosa and San Antonio ISD Superintendent Pedro Martinez. Both are constantly out telling the story of their successes, lobbying for more money. Brownsville administrators don’t show up as frequently.

And few people make it down to Brownsville, Rau pointed out. With its small media market and remote location, “Brownsville is so far removed from most people’s reality.”

For those who do visit, though, one hour with Principal Theresa Villafuerte sheds a beam of light on the phenomenon. After eight years at Gallegos, Villafuerte is deeply connected to the community she serves. Cameron Park is an unincorporated area of Cameron County on the edge of Brownsville ISD on the Texas-Mexico border. Under Villafuerte’s leadership, the Gallegos team has been able to keep up with the constant innovation stemming from Brownsville ISD central administration, while at the same time offering basic supports to ensure kids are ready to learn. When children come to her school, Villafuerte does not assume anything — she’s ready to provide meals, clothing, or whatever support they need.

At the same time, she said, her staff celebrates the rich resources the community does provide. Many families are deeply committed to Gallegos, volunteering well after their children have graduated. Some of the “parent” volunteers, Villafuerte said, have been regularly helping out for over 20 years. When she made it known that she wished for preschool-sized picnic tables for the courtyards, a parent made miniature versions of the school’s full-size tables.

Families get to choose which elementary school they attend in Brownsville ISD, and the district offers transportation for each option. Gallegos is also the school of choice for many students who require special education services, and those parents are very committed, Gallegos said. Special education students rarely test on par with their peers, but Gallegos comes close, with 71 percent of students who receive special education services passing their state tests, compared with 41 percent of all Texas students.

To get those results for children in extreme poverty, Villafuerte said, the school’s pre-K for 3-year-olds is incredibly valuable.

“If we can get them early, we know we’ve got them,” she said.

Many of the parents of the 3-year-olds are new or young parents, and that affords Villafuerte and her team the chance to help them develop their parenting skills. She says that although she’s been at Gallegos for only eight years, some of her earliest fifth-graders already have kids at the school.

Brownsville’s commitment to pre-K for 3-year-olds (pre-K 3) has been a scrappy, patchwork effort. Texas funds half-day pre-K for certain 4-year-olds, but nothing for younger children. In 2015, state Rep. Eddie Lucio III drafted legislation that allowed the district to graduate high school students in three years, and then take the money from what would have been their senior year and spend it on pre-K 3.

Lucio said in a press release at the time of the bill’s passage that it was based on comprehensive research “proving the positive effects of prekindergarten programs on the success of young children.” He called the reallocation of funds “a perfect, cost-neutral opportunity to take advantage of school districts’ current savings.”

However, sometimes one innovation can step on the toes of another. The following school year, the district switched all of the high schools to the early college model, which allows students to take college courses while in high school and graduate with an associate’s degree. The chance to earn college credit meant that fewer students graduated early.

The pre-K 3 program is now funded by a “kaleidoscope” of sources, according to Zendejas, who said the district has extended itself financially, “knowing that this investment will pay for itself in the long run.”

Social capital

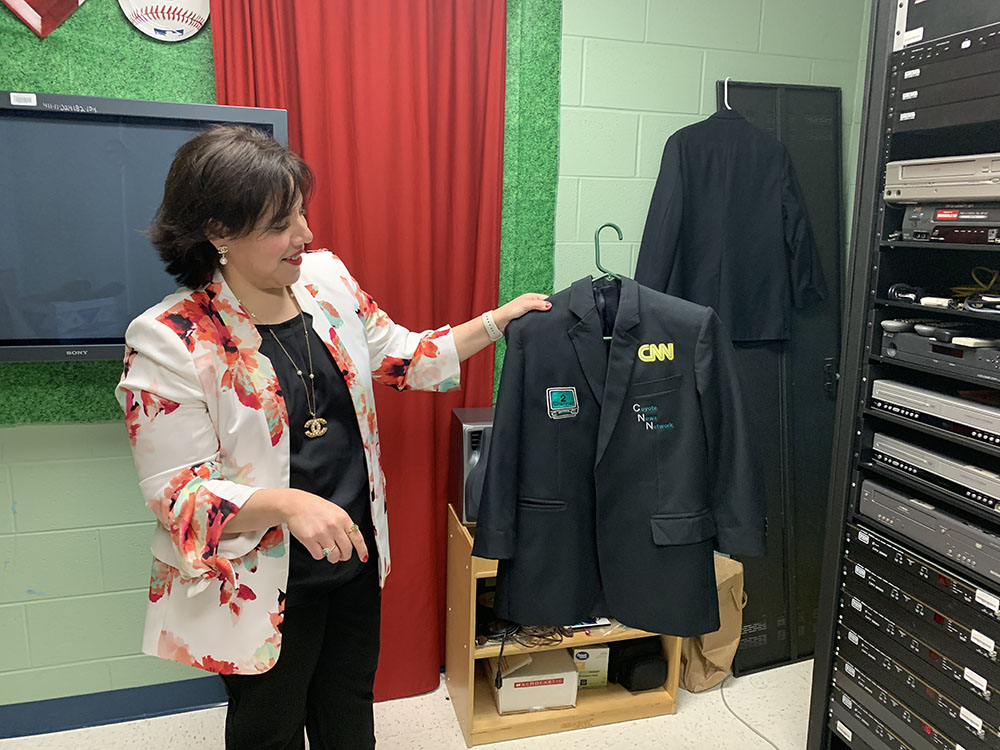

At Hudson Elementary, a closed-circuit “television station” allows the fifth grade to broadcast the morning announcements, complete with a profile segment on colleges students might want to consider, a word of the day, weather, and sports. The music room is equipped with some 10 pianos and more than 20 guitars. Elementary students are learning music theory. In the courtyard, where classes eat outside with their teachers once per week, the fifth-graders have covered the concrete in original poetry, written and illustrated with sidewalk chalk.

All these cheerful details contribute to a sense of purpose and belonging, says Principal Rachel Ayala.

“It’s not just about math, reading, science, and social studies,” Ayala said, “We’re a micro-community.”

Ayala enlists macro-community partners to populate the kid-sized world. A mini-bank and grocery store are funded by a local bank and neighborhood grocery store. Students learn financial literacy and supply chain basics. They grow their own vegetables and learn how to incorporate them into meals. Parents who do have the means to contribute do so generously, she said, and even non-parent neighbors have adopted the school, donating funds for pizza parties and all sorts of extras.

As at Gallegos, signs of parent engagement are everywhere. An elaborate Little Free Library sits in the Hudson foyer, built and donated by a parent craftsman.

Compared to Gallegos, Hudson Elementary feels like “the rich school.” It’s not. Only 8 percent of Hudson students come from families who make more than $44,000 per year.

However, economic disadvantage doesn’t tell the whole story. It’s actually a rather blunt instrument to measure student need.

In most of the zip codes served by Brownsville ISD, around 10 to 12 percent of homes with children are single-parent. That’s about 7 to 9 percentage points lower than in the poorest zip codes in San Antonio. Homeownership is also high in Brownsville, which may be facilitated by lower housing prices. The median home value in the eight zip codes served by Brownsville ISD is $78,700. The median home value for the entire city is $88,900, according to the Zillow Home Value Index.

This sort of stability in the midst of poverty allows for a lot of community cohesion, or what scholars call “social capital.” Social capital, traded and cultivated by Principal Ayala, is the true currency in Hudsonville.

The war room

At Annie S. Putegnat Elementary, the oldest campus in Brownsville, the halls shine. Nothing seems to be in disrepair. The maintenance staff is on top of every need, Principal Aidee Vasquez said, and that is part of showing the children of Brownsville that they are worth the district’s best effort.

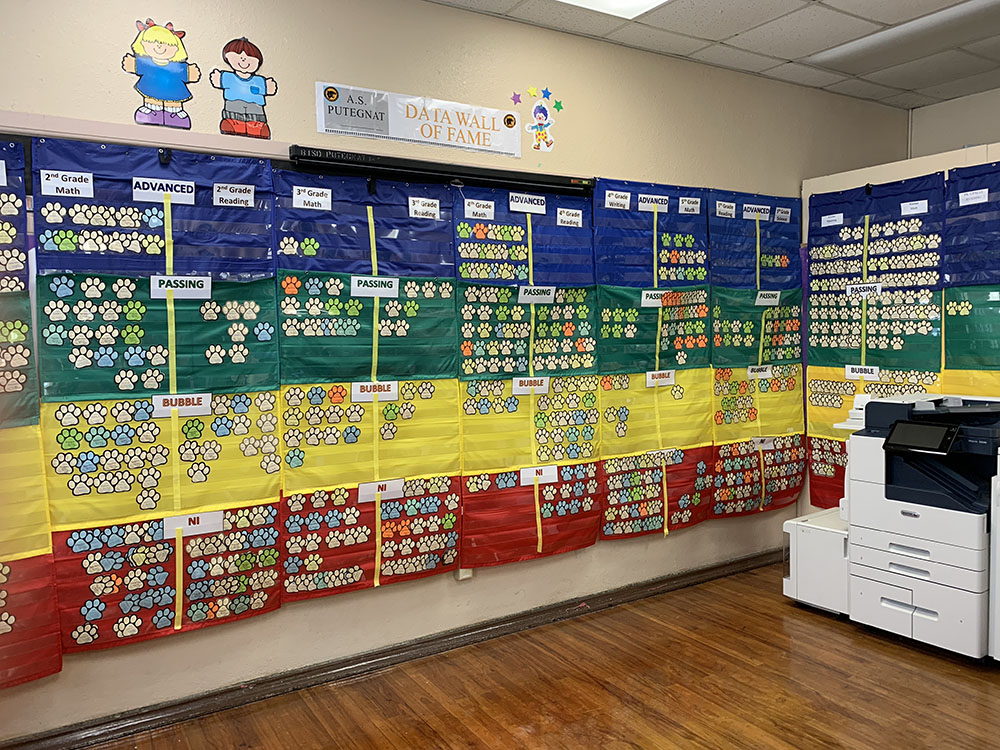

Best efforts show up again in Putegnat’s “war room,” where the walls are covered in paper paw prints. Each one represents a data point — how each and every one of Putegnat’s 487 Panthers is progressing in reading, math, writing, and science. Vasquez obsesses over the data daily, deploying academic support wherever the micro-data show that it’s needed. They don’t wait to see how things play out. They intervene immediately for each child, each class, and the school as a whole.

“You have to be bold and confident about the decisions you’re making,” Vasquez said.

This attention to detail is borne out in Putegnat’s state test scores. In 2015, only 54 percent of Putegnat students passed their state science tests; all other subjects were in the 60s and 70s. In 2018, 91 percent of students passed their science test. All but one of the other subject scores were in the 90s.

Every single campus has a war room, meaning that all of Brownsville’s 45,000 students are being closely monitored for performance. With Texas’s new A-F grading system now in effect, every single one of those data points has gained new significance.

The district earned a B in the first year of the rigorous (and widely bemoaned) new grading system, better than some of Texas’s larger districts, such as Fort Worth ISD, and those with significantly more wealth per student, such as Midland ISD.

Associate Superintendent Alma Cardenas-Rubio said that the district missed an “A” rating because of the scores at one campus, Lincoln Park High School. It is the alternative school for teen moms. While the district does plan to appeal those scores, she’s glad to know where they need to improve.

“Even when you’re doing great,” she said, “you can’t stop doing greater.”