by Sophie Quinton

Julius Dancy’s parents couldn’t afford to send him to a four-year college. His high school grades, he admits, weren’t great, so he didn’t qualify for merit scholarships.

But Dancy lives in Tennessee, where since 2014 the state has promised free community college for young people who enroll full time, do eight hours of community service a semester and earn a “C” average.

Dancy, 18, is now in his first year studying business at Southwest Tennessee Community College in Memphis. The state’s tuition-free college program made college possible for him, he said.

“I wouldn’t have been able to go to college without Southwest offering the things that they do,” he said in an interview with Stateline. As for many of his high school classmates, he added, “I know for a fact that they wouldn’t have been able to go to college without the Tennessee Promise.”

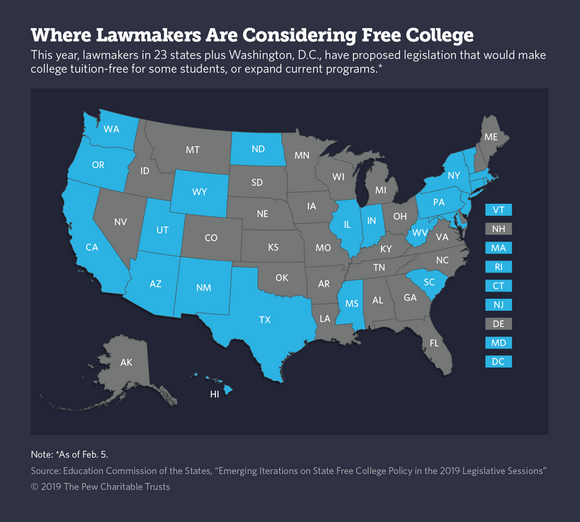

Programs such as Tennessee’s have caught the public imagination. At least 15 states — some led by Republicans, others by Democrats — now cover two-year or four-year college tuition for some students. Lawmakers in 23 states are floating “free college” bills this year. And several high-profile Democratic presidential candidates want to not only make college tuition-free but also eliminate student loan debt.

But policymakers are sparring over who should get aid, and how much.

Critics on the left want to expand free college to more students and cover more than tuition. They argue that in many states, program dollars flow to wealthier students and don’t defray expenses such as textbooks, course fees and transportation.

Critics on the right worry that universal free college programs fail to prepare students for the workforce. Some also warn against creating expensive new entitlement programs.

In Michigan, Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s call this year to increase scholarship aid and make community college tuition-free was coolly received by the Republican-led legislature. In remarks to reporters, Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey said he’s not sure that the high cost of college is the problem.

“I think value is, and we don’t do a good enough job measuring value,” he said — that is, ensuring that college degrees pay off. Whitmer’s goal to ensure that 60 percent of Michigan adults have a college credential by 2030, he said, “is pretty much meaningless. What if all those achievements were in underwater basket weaving?”

Budget constraints often force lawmakers to scale back their free college plans. “We’re seeing more and more narrowly tailored programs that aren’t really billable as the ‘universal free college,’” said Sarah Pingel, senior policy analyst at Education Commission of the States, the nonprofit arm of an interstate compact on education policy.

A Promise to Students

Free college programs date back decades — Indiana, for example, has offered some students full scholarships since the 1990s — but they began to multiply in the years after the Great Recession, as college debt soared and forecasters predicted that most future jobs would require advanced training.

Offerings range from city programs funded by private donors to state grants for workforce-oriented degrees and, in New York’s case, a four-year scholarship that converts to a loan if recipients leave the state after graduation.

But perhaps the best-known example is the Tennessee Promise, which attracted lots of media attention when it was signed into law and inspired a flurry of copycat programs.

The grant for recent high school graduates covers any last community college tuition and mandatory fee dollars not already covered by other grants, such as the federal Pell Grant for low-income students and Tennessee’s merit scholarship. It’s known as a “last dollar” funding model.

In 2015, the first year of the program, community colleges enrolled almost a quarter more recent high school graduates — and almost half of the new enrollees didn’t get any Promise dollars because they qualified for other grants.

Enrollment has jumped in other states with similar “last dollar” programs. “We have seen a significant boost in this post-high-school population,” said Sara Enright, vice president for student affairs at the Community College of Rhode Island. “And I think it’s because when you put out a free college banner, it’s just a simple message that draws people in.”

In 2016, the year before the Rhode Island Promise program began, 1,100 recent high school graduates enrolled in the state’s community college. By last fall that group’s enrollment had more than doubled.

Most states attach strings to free college programs, such as requiring students to attend full time. That’s helped boost graduation rates in Rhode Island, where Enright expects 18 percent of the first Rhode Island Promise cohort to graduate after two years in community college, triple the typical graduation rate. Most CCRI students attend part time.

Promise students in Tennessee also graduate at higher rates than their peers. But the students who receive the most Promise aid — mostly men who don’t qualify for need-based or merit aid — are the least successful.

Just 11 percent of such students in the program’s first cohort completed a degree or certificate in five semesters, compared with about 20 percent of Promise students overall.

The director of policy at the Tennessee Board of Regents’ Office of Policy and Strategy, Amy Moreland, said such students are more likely than other students in the Promise program to graduate with a technical certificate that prepares them for a specific job.

The free college concept has become so popular — particularly within the Democratic Party — that some states have rebranded existing financial aid programs to include the word “Promise.” That language mirrors the College Promise Campaign, a nonpartisan nonprofit announced by then-President Barack Obama in 2015.

Generous state financial aid has allowed Californians to attend two-year colleges for free for decades. But in 2017 the state community college chancellor’s office renamed a longstanding grant for low-income students as the “California College Promise Grant.”

“That was a clear renaming of an existing program in order to capitalize on some of the free college momentum across the country,” said Debbie Cochrane, executive vice president of the Institute for College Access and Success, an education nonprofit with offices in Oakland, California, and Washington, D.C.

Separately, California lawmakers last year passed legislation that freed up more money for two-year colleges to spend either on tuition aid or on services that might help students graduate or defray other costs, such as textbooks. Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom wants to add $40 million this year.

Defining ‘Free’

But four-year colleges and universities worry that such programs could hurt their finances.

“If a significantly higher number of students attend a community college as opposed to going to a four-year college, it could possibly weaken the four-year college funding model,” said Tom Harnisch, director of state relations and policy analysis at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities.

That’s because freshman and sophomore-year lectures, crammed with hundreds of students, are a money maker for universities that help subsidize smaller upper-division seminars, he said. Even community college students who transfer to four-year schools usually enter as juniors, meaning they miss those lucrative large lectures.

And paying for free college has been a challenge for lawmakers. Tennessee, unique among states, has an endowment comprised of lottery reserve funds that pays for Tennessee Promise. The program cost about $30 million last school year. Lawmakers created a similar grant for working adults two years ago.

Budget limitations this year could table proposals to expand free college in Oregon and New Jersey. Lack of funds in 2017 led Oregon colleges to temporarily restrict eligibility for Oregon Promise.

Some conservatives argue that free college programs pass along increasingly high costs to taxpayers. “The state-level programs for free community college, or free four-year college, have the same underlying problem, which is they don’t address the root causes of tuition inflation,” said Mary Clare Amselem, a policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation, a think tank based in Washington, D.C.

She also questioned the push to encourage students to attend community college, given that many have dismal graduation rates. Twenty-four percent of first-time students graduate from public two-year colleges in three years, while 60 percent of first-time students graduate from public four-year programs in six years, according to federal statistics.

Lawmakers might want to consider spending money on high school vocational training or apprenticeships instead, Amselem said. “We should have multiple pathways and options to career success.”

Meanwhile, some left-leaning groups have criticized free college programs for spending money on wealthier students and failing to address costs of attendance beyond tuition.

Tiffany Jones, director of higher education policy at the Education Trust, a national nonprofit focused on promoting equity in education, analyzed the 13 free college programs active in 2017 and found eight used a last-dollar model like Tennessee’s. “That meant, obviously, that there was no financial benefit for the lowest-income students,” she said.

Programs that only offer aid to low-income students, such as Maryland’s, or provide Promise aid before other grants, allowing total aid to exceed tuition costs — as Oklahoma and California do — promote equity by directing more aid toward students who need it most, Jones said.

And many grants promoted as “free college” don’t actually cover the full cost of going to college, she said.

Media coverage of Oregon’s “free college” program can be misleading, said Juan Baez-Arevalo, head of Oregon’s Office of Student Access and Completion. “It’s not free,” he said of the grant. The Oregon Promise program covers community college tuition but not course fees, textbooks, transportation or room and board.

Those other costs can outpace tuition costs. At Central Oregon Community College, for instance, a student living locally and studying full time would owe about $2,376 a year in tuition. But add college fees, books, transportation and living expenses, and cost of attendance balloons to an estimated $13,764 if the student lives at home with her parents.

The perception that free college is just a middle-class handout has made some education advocacy groups reluctant to support the policy — even in states such as New Jersey, where Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy is trying to target aid to the neediest students, including working adults studying part time.

“Sometimes, I just think support is influenced by that national rhetoric that doesn’t align with values we have here,” said New Jersey Higher Education Secretary Zakiya Smith Ellis.

Some mayors around the country are now afraid that if they start a free college program they’ll face criticism for not making aid generous enough, said Krissy DeAlejandro, executive director of tnAchieves, a privately funded nonprofit that supports the Tennessee Promise program by, among other things, training and recruiting volunteer mentors.

“I think that’s stifling,” she said. “When are you sacrificing the great for the perfect?”

DeAlejandro said that while more well-off students might receive more Promise money — the average award in spring 2017 was $1,011 — lower-income students can receive more non-tuition support, such as academic advising and coaching provided by her nonprofit.

Dancy said that support for Tennessee Promise participants, such as mentors, advisers, and reminder emails and texts, has helped him stay on track. When his grades fell this semester, he was instantly surrounded by adults pointing him toward tutoring resources and reminding him to stay focused.

“To me, it doesn’t even feel like it’s a scholarship,” he said. “It feels like more of a family thing.”

Sophie Quinton writes about fiscal and economic policy for PEW’s’ Stateline.