by Ryan Berg

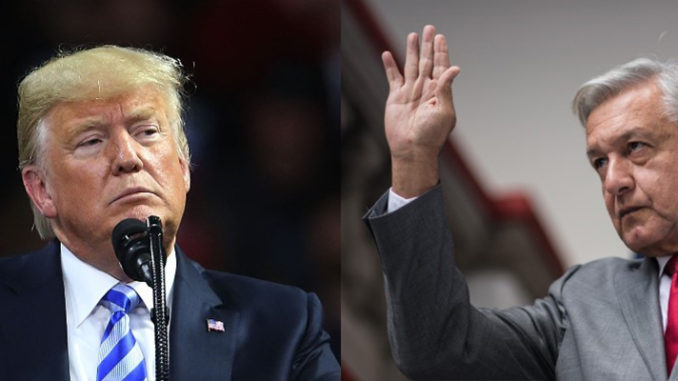

Since late January, thousands of would-be asylum applicants have been held up just outside of the U.S. border with Mexico, where they have been forced to wait their turn to speak to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The growing humanitarian situation—camps for migrants are overcrowded, unhygienic, and dangerous—has renewed focus on Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s call for a Central American Marshall Plan, through which $30 billion would be channeled toward regional development in an effort to ease migration pressures. López Obrador, popularly known as AMLO, has set a goal of funding the plan by May, and U.S. President Donald Trump, eager to halt immigration to the United States, agreed to participate to the tune of $5.8 billion.

Addressing the root causes of migration—insecurity, violence, and lack of opportunity—makes sense. Both the United States and Mexico should want to ensure that emigration is an option for Central Americans rather than a necessary step to a life of dignity. However, López Obrador’s strategy rests on a common misunderstanding of the realities of the original Marshall Plan. Namely, it was not an infusion of cash that caused a European resurgence but a targeted investment that channeled and amplified an economic recovery that was already underway. It did so by placing significant restraints on the policies of recipient countries, prohibiting the nationalization of companies, and mandating strict exchange rate controls, balanced budgets, and intrusive checks on national economic policy.

As a result, the $17 billion (nearly $200 billion in 2019 dollars) that the United States invested in Europe between 1948 and 1951 became a concerted effort to build resilient political and economic institutions that last to this day. There are reasons to be skeptical that a López Obrador-Trump partnership would do the same.

First, both López Obrador and Trump have demonstrated disdain for the kinds of political institutions Central America must bolster. For his part, López Obrador reveres and patterns himself after the great revolutionaries of Mexico’s past, who preferred to lead by imposition and knew nothing of checks and balances. It is telling that one of his first major political maneuvers—an attempt to address large-scale petroleum theft—involved placing the Mexican armed forces in charge of combating corruption. The move might have been crafted to signal his seriousness, but it demonstrated that López Obrador lacked the will to undertake the painstaking work of building strong and independent institutions that could effectively regulate industries and manage corruption in the long term. Indeed, López Obrador has centralized executive power at the expense of the judiciary and legislature, run roughshod over the country’s federal system by appointing loyal superdelegates to try to displace governors and mayors, and engaged in a broader offensive against independent government institutions that pose a challenge to his accumulation of power by cutting their budgets and hollowing out their bureaucratic personnel.

Trump, too, has a problematic relationship with political and judicial institutions. He has personally attacked judges for decisions he disagreed with and for their ethnic heritage, bemoaned the independence of the Federal Reserve, and directed the FBI and the Justice Department away from investigations aimed at his advisors and toward political opponents such as former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Trump’s affinity for strongmen in Ankara, Manila, Moscow, and Riyadh, meanwhile, is well documented.

It is doubtful that two leaders who have displayed such disregard for the importance of abiding by democratic norms and institutions would have the patience or the appreciation to correctly identify and make the right long-term investments to support democracy in Central America. The price of getting it wrong is steep—often more harmful than not sending aid at all. In fact, poorly conceptualized foreign aid can stymie the deepening of democracy by propping up bad actors and providing them with an economic lifeline to mask their lack of success on reform.

A second reason to doubt the viability of a Central American Marshall Plan is that the United States has already committed billions of dollars in aid and favorable trade deals to Central America with little macroeconomic growth to show for it. The recent Alliance for Prosperity, a scheme conceived in the wake of the 2014 unaccompanied minor crisis to which the United States gave $2.6 billion, has produced few noteworthy economic accomplishments. The United States has also promoted Central American economic growth through free trade agreements. Since 2004, for example, the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement has granted “most favored nation” status to the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. According to the U.S. Trade Representative’s Office, almost 80 percent of exports from the region enter the United States tariff-free.

In short, some of the most important policies for Central American economic growth have already been in place for more than a decade. Yet, growth and economic development remain stagnant due to factors like large-scale migration, insecurity, and a stubbornly large informal sector. For instance, a recent Wilson Center report on innovation and productivity in the region noted that a Latin American worker in the 1970s produced 82 percent of what a U.S. worker produced; today, that figure stands at 55 percent. At least partially because Central American nations have been unable to increase productivity and sustain economic growth, remittances still represent about 15 percent of the region’s GDP.

A final reason to doubt the success of a Central American Marshall Plan is that the region lacks willing partners on the ground. In the Northern Triangle—made up of the countries from which most asylum-seekers come to the United States—many political leaders are engaged in democratic backsliding and serious corruption scandals. In Guatemala, for example, President Jimmy Morales is busy dismantling the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (known as CICIG in Spanish), a U.N.-led anti-corruption body working with Guatemalan prosecutors to uproot the vestiges of organized crime that have stubbornly clung to power since the country’s civil war. In Honduras, President Juan Orlando Hernández remains in power after a highly disputed (and potentially rigged) election. His brother, Tony Hernández, was arrested in Miami, where he was accused of working with some of the largest drug trafficking networks in Central America. And El Salvador just elected a telegenic young president whom some observers have linked to the well-known drug kingpin José Luis Merino. These figures are hardly the type to effectively collaborate with the United States and Mexico—turning the aid into more of a handout than a return on investment.

Before World War II, most Western European countries already had some experience with democracy and higher living standards. The Marshall Plan helped get these societies back on their feet, but high levels of human capital and development meant that the groundwork for success already existed. As Trump and López Obrador are poised to discover, restoring something that once existed and bringing something new into being are entirely different things. Trump and López Obrador ought to be commended for their ambition—if not for their correct reading of history, foresight, patience, and follow-through.

Ryan C. Berg is a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where his research includes Latin American foreign-policy issues.