by Admin

Timothy P. Carney’s latest hard-hitting analysis identifies the true factor behind the decline of the American dream: the collapse of the institutions that made us successful, including marriage, church, and civic life.

While America is generally getting wealthier, disturbing trends among the working class are bubbling up to the surface. Wages still lag. Suicide, overdose, and other deaths of despair are rising. Marriage is on the wane.

It’s no wonder Donald Trump proclaimed “the American dream is dead.” It shouldn’t have surprised anyone that voters agreed. That dour proclamation sounded absurd to many elites, who lived in places where the american dream was alive and well, but it resonated in working-class places. Any purely economic account of the working-class woe falls short. The accounts that cite “cultural anxiety” tend to simply blame the suffering as a way to avoid facing the fact: not all the changes in America since 1960 count as “progress.”

It’s no wonder Donald Trump proclaimed “the American dream is dead.” It shouldn’t have surprised anyone that voters agreed. That dour proclamation sounded absurd to many elites, who lived in places where the american dream was alive and well, but it resonated in working-class places. Any purely economic account of the working-class woe falls short. The accounts that cite “cultural anxiety” tend to simply blame the suffering as a way to avoid facing the fact: not all the changes in America since 1960 count as “progress.”

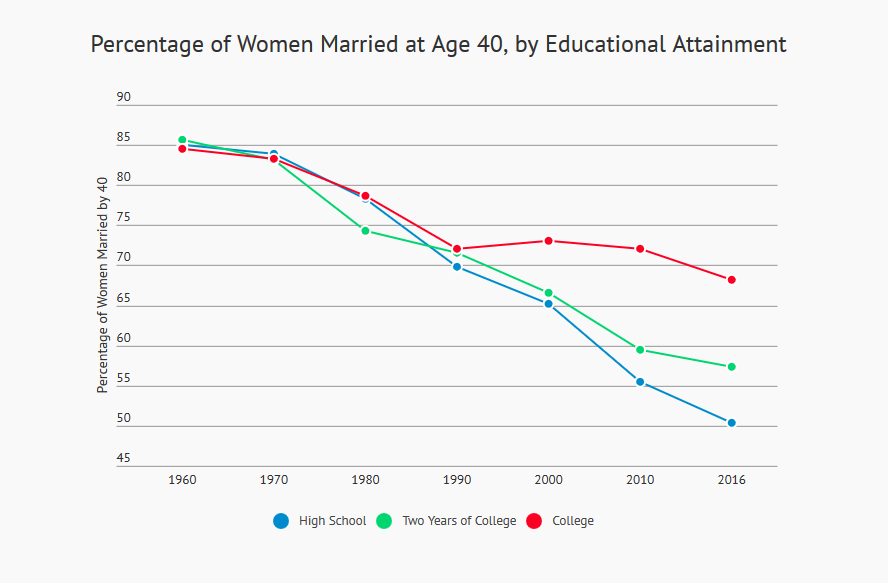

Marriage is on the decline, and the problem isn’t wealthy elites adopting European mores or opting for career instead of family. More education and higher wages for women are causing many to delay marriage, but the real dropoff isn’t occurring among the Wesleyan alumnae, but among the women and men who don’t finish college or never attend.

Whereas marriage was equally the norm across education levels back in the 1960, the last two generations have seen a clear class distinction emerge.

This blue-collar retreat from marriage, like the other negative social trends among the working class, is not due to some anti-family belief system or some perfidy in rural America. It’s due to the collapse of the infrastructure around which people build families — that is, the collapse of communities and the hollowing out of institutions of civil society.

It’s a story of alienation. Alienation is what happens when people lack community institutions to connect them with others. These institutions provide miniature safety nets, they provide meeting grounds, they provide modeling and mentoring, and they provide meaning and purpose.

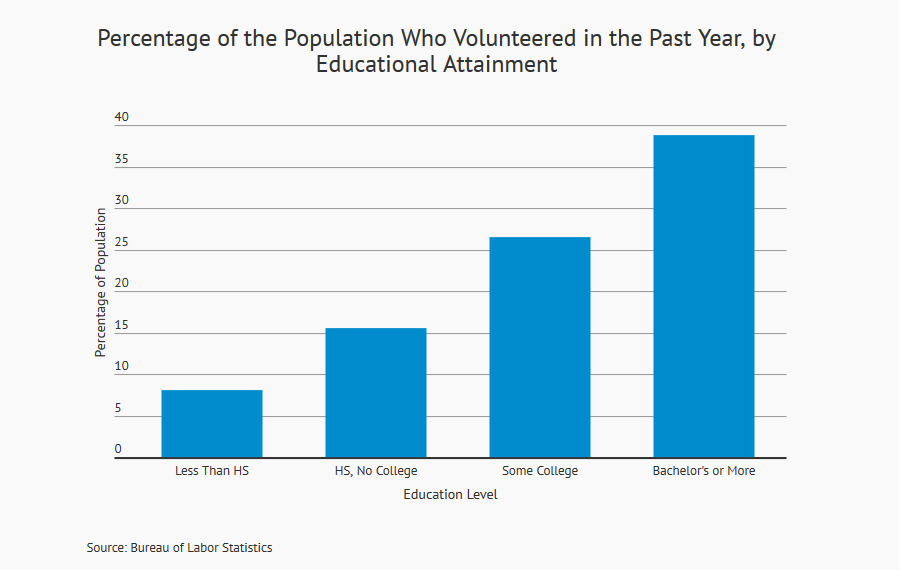

Upper-middle-class places packed with college graduates still have strong communities, as do a few particularly strong religious communities. But among the working class, there’s less and less attachment to community groups, clubs, teams, and volunteer organizations.

Of course, when we talk about community organizations in America, historically that mostly means church.

About half of all civic activity in the US originates in the church. This includes religious activities, but also soup kitchens run out of the church basement, tee-ball teams organized around congregations, social clubs organized within parishes, and so on.

The plague of alienation in America is, above all, a matter of secularization — a matter of the decline of the American church.

In the working class, the decline is more severe, and it’s also more harmful. The elites who leave church, or lose church, have many other institutions on which to fall back, including strong public schools, alumni associations, professional associations, and more. For the working class, the loss of church means alienation.

In the working class, the decline is more severe, and it’s also more harmful. The elites who leave church, or lose church, have many other institutions on which to fall back, including strong public schools, alumni associations, professional associations, and more. For the working class, the loss of church means alienation.

We shouldn’t read this retreat from community involvement as some sort of misdeed or vice among the working class. It’s more of an affliction.

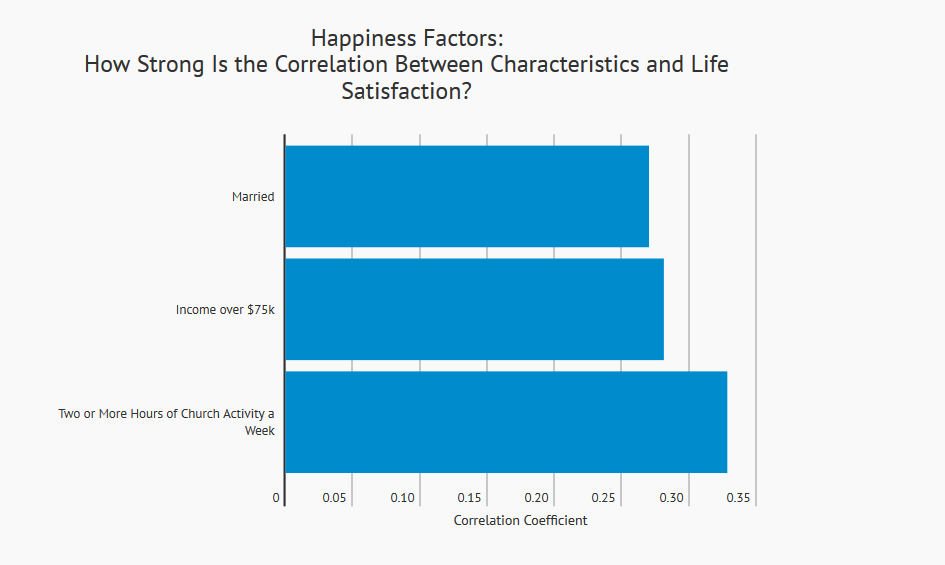

We crunched numbers from the American Time Use Survey and found something interesting. Controlling for many other factors, including income and education, spending a couple of hours at church had a huge impact on life satisfaction.

Below are the coefficients we found after doing our regression analysis. The larger the coefficient, the stronger the correlation between that trait and happiness.

While making more money had a strong correlation with happiness, belonging to a church seems to have had an even stronger impact.

And this brings us back to Trump, and the 2016 election, particularly the Republican primary.

Early in the primary, when 17 Republicans were running, Trump’s appeal was to those who agreed that the American dream really was dead. While Ted Cruz appealed to the religious right, Marco Rubio won college-educated conservatives, and John Kasich did well among moderate elites, Trump won among the alienated.

Again, we’re not talking about the general election where Trump faced Hillary Clinton and the votes broke down more along party and ideological lines. We’re talking about the early primaries. In those early contests, poll data from the Democracy Fund’s Voter Study Group show that Trump did best among those who went to church the least.

Perhaps the easiest way to see alienation as the first driver of early Trump support is to look at where Trump did worst in the early primaries.

Below are all the counties (excluding those with fewer than 2,000 votes) where Trump got below 20 percent of the Republican primary or caucus vote. All but two fit into three categories.

Twenty-five are either among the 25 most college-educated counties in America (the Elites), more than 50 percent Mormon, or among the 20 most Dutch counties. The two remaining counties, Brazos and Charlottesville, are college-dominated counties.

In these places — with colleges, churches, and elite institutions — the American dream seemed most alive.

Perhaps the easiest way to see alienation as the first driver of early Trump support is to look where Trump did worst in early primaries. In these places — with colleges, churches, and elite institutions — the American Dream seemed most alive.

Timothy P. Carney is commentary editor at the Washington Examiner and a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of Alienated America: Why Some Places Thrive While Others Collapse, from which this is adapted.