b

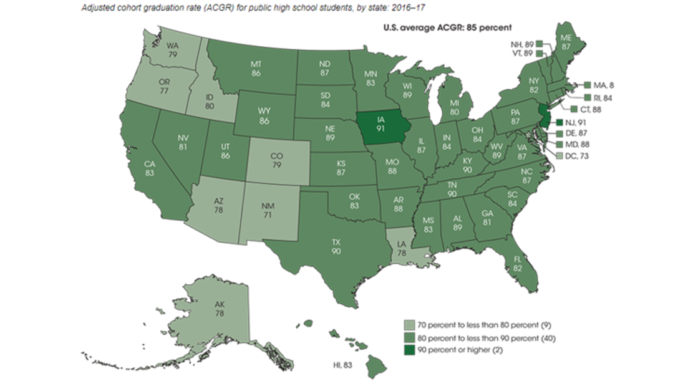

The U.S. high school graduation rate has risen for yet another year, to a new all-time high of 84.6 percent. But even as some celebrated the steady gains in high school completion, others worried that the pace of improvement is slowing, and that the numbers tell a false story.

New figures released Thursday by the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics show that 84.6 percent of the students in the class of 2016-17 earned diplomas in four years. That’s a half-point better than in 2015-16, when the graduation rate was 84.1 percent.

Leaders of GradNation, a campaign to raise high school completion rates, rang an alarm bell as soon as the new data came out, warning that it’s the first time since 2011 that the graduation rate hasn’t shown year-to-year improvements of almost a full percentage point.

The half-point rise is “a sobering reminder that we cannot afford to be complacent in our efforts to place more young people on the path to high school graduation and postsecondary success,” Bob Balfanz, who works with GradNation and leads the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, said in a statement.

“Given that most jobs today and in the future require postsecondary education or training, a high school diploma is an essential first step to adult success after high school.”

‘Losing Momentum?’

“We are losing momentum and urgently need to rededicate ourselves to finish the job” of meeting the nation’s 2020 goal of having 90 percent of students finish high school in four years, John Bridgeland, the CEO of Civic Enterprises, part of the GradNation initiative, said in a statement.

Monika Kincheloe, a senior director at America’s Promise Alliance, a partner in the GradNation campaign, said that one theory for the slowdown in improvement is that students are disengaging from school because they’re getting too little support for learning social-emotional skills such as persistence, even as their schools have ratcheted up academic expectations in the “college and career-readiness” push of the last decade.

Questions persist, also, about what is fueling the steady rise in high school graduation rates. While many schools have been focusing energy on better supporting students so they can finish high school, studies and anecdotes suggest that some could have edged into dubious tactics—such as creating diploma mills with quick, online catch-up courses—in order to look good when annual accountability reports come out.

“We’ve been watching the rise of credit recovery and alternative pathways to graduation,” Kincheloe said. “There’s a lot we don’t know about these thousands of kids sitting at rows of computers, about the rigor of those programs.

“We’re aware of this gaming behavior [by schools and districts.] And they need to be brought into accountability” for the quality of those programs, she said.

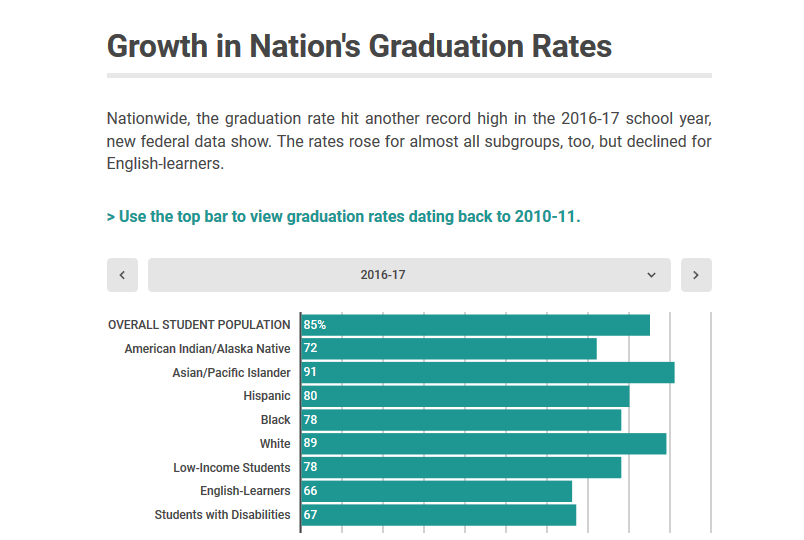

Even as the pace of overall growth slowed in the graduation rate between 2016 and 2017, the new figures showed gains for most of the student groups who have historically struggled to finish school. And they showed one decrease: for English-learners.

Here are the highlights of the subgroup changes in the U.S. high school graduation rate from 2016 to 2017:

- + 1.6 percentage points: Students with disabilities. 2017 graduation rate: 67.1 percent

- + 1.4 points: African-American students. 2017 graduation rate: 77.8 percent

- + .7 of a point: Latino students. 2017 graduation rate: 80 percent

- + .7 of a point: Students from low-income families. 2017 graduation rate: 78.3 percent

- + .5 of a point: American Indian/Alaska Native students: 2017 graduation rate: 72.4 percent

- + .4 of a point: Asian-American students. 2017 gradution rate: 91.2 percent

- + .3 of a point: White students. 2017 graduation rate: 88.6 percent.

- – .4 of a point: English-learners. 2017 graduation rate: 66.4 percent

Kincheloe said the big graduation-rate gain among students with disabilities prompted an “eyebrow raise” among leaders of GradNation, and they “flagged it as something to look into.”

The explanation for those gains isn’t clear yet, she said, but she and her colleagues wonder whether it was fueled by states expanding the definition of “regular” diploma so that it included more students with disabilities. The Every Student Succeeds Act requires states to calculate their graduation rates using only “regular” diplomas awarded to “a preponderance” of students.

Kincheloe said she worries that graduation rates declined among English-learners because districts are overwhelmed by the influx of immigrant students. “We are hearing that schools aren’t sure what to do with those students, that teachers are creating pop-up classrooms for them,” she said.

Catherine Gewertz is a senior contributing writer for Education Week. She covers assessment, and pathways through middle and high school. She is the author of the blog High School & Beyond. Learn more about her and our other Edweek experts’ background and expertise here.