by

Before the holiday break, I wrote a series of posts discussing how we might turn the “End of Education Policy” (as I see it) into a Golden Age of Educational Practice. It’s time to pick up where I left off.

To be honest, much of what I published in late 2018 amounted to throat-clearing, a warm-up before the main event. My basic (and hardly brilliant) argument was this:

• It’s possible to identify instructional practices and materials that are more effective than others at improving student outcomes, tapping the tools of science.

• To do so, we need to collect lots more information about what’s going on in America’s classrooms, and be willing to experiment with new approaches.

• Then smart people with credibility with educators need to separate the wheat from the chaff, developing practitioner guidance based on the best currently available evidence.

Not that any of this is simple, as it takes serious investment in R&D, tackling tough student privacy issues, and dealing with the inherent complexity and heterogeneity of our schools. But it’s way more doable than the next phase of the research-to-practice cycle: getting schools to actually use the stuff that works.

This of course has been the point of more than three decades of education reform. We accountability hawks, hoped that by holding schools and their leaders accountable—with school ratings, threats of painful interventions, and so forth—they would work harder and smarter to find evidence-based solutions to their problems. That’s also been an important goal of the school-choice movement—to pressure traditional public schools via competition to get better, or at least better at serving their customers.

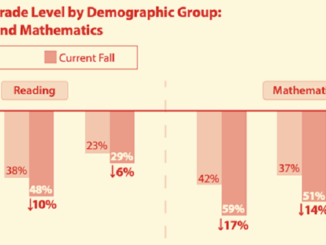

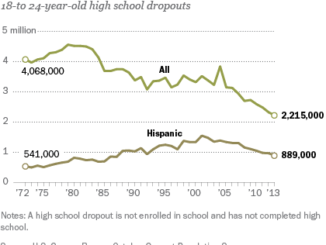

There’s some evidence that it worked, at least a little. The test-based accountability reforms of the late 90s and early 2000s appear to have boosted the math scores of low-income and low-performing students significantly; NAEP scores also show a bump in reading for the same students in the early grades. Meanwhile, many school-choice studies show positive findings with respect to “competitive effects.”

But as everyone knows, how schools achieved those better results has raised a lot of questions. Did they actually improve teaching and learning, adopt proven curricula, and provide better training and support to teachers? Or did they just narrow the curriculum, focus on test-prep in its several guises, and tighten the screws on overburdened teachers? The honest answer is probably “both” or “it depends on the school”—but I sure can’t spot any signs that schools nationwide suddenly got religion about finding proven curricula and evidence-based practices and implementing them faithfully in large numbers of their classrooms.

Back to today and the main event. How might we do better going forward? Let’s assume that our lighter-touch accountability systems and slow-growing choice sectors are here to stay. And that there are at least a few examples of “evidence based practices” that could make a significant difference in improving student outcomes if implemented well in our schools. (Though let’s also be humble—there may not be more than just a few.) How might we dramatically increase the chances that our schools scale up the most effective practices, resulting in significantly better outcomes for students?

There are a few actions that would make sense in a sane world—but seem unlikely to happen in the world we actually inhabit. At the top of the list would be convincing schools of education to teach evidence-based practices and a respect for the science of learning. Maybe various efforts to reform ed schools will succeed where others have failed, but I’m not holding my breath.

I’m also not expecting the ESSA requirements for schools to use “evidence-based practices” to add up to much. That term is plenty elastic, so our institutions can do pretty much anything they want and still claim to be in compliance with the law.

So what might actually work? I see six plausible approaches that might be embraced by local communities, state education agencies, and/or philanthropists, under two categories:

|

A Culture of Improvement • Develop school improvement networks dedicated to searching for evidence-based solutions to problems of practice. • Expand high-quality charter schools with a proven record of respect for evidence and a culture of continuous improvement. • Scale up instructional coaching to help teachers implement evidence-based practices in their classrooms. |

Tools and Technologies • Develop and market tools, such as curricular products, that are teacher-friendly and have a strong evidence base. • Develop and scale up new school models that bring several evidence-based tools or practices into a coherent whole, along with new, innovative approaches. • Clear the policy barriers that make it hard for schools to purchase the best tools and technologies, especially outdated procurement procedures. |

In coming weeks I’ll unpack these various options, but it’s worth acknowledging up front that most of them can work well in tandem. Several high-quality charter school networks, for example, embrace the “improvement science” approach popularized by Tony Bryk and his colleagues at the Carnegie Foundation. And of course, new school models are often easiest to implement in the charter sector, given their opportunity to start fresh. Likewise, we’re learning that instructional coaching can be a powerful improvement lever—but especially if connected to a well-designed, standards-aligned, and teacher-friendly curriculum.

Am I forgetting some other ways to scale up evidence-based practices? And do you think that some of these approaches are clearly superior to others? Let me know, and stay tuned for more discussion about their various pros and cons.

Mike Petrilli is president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, and executive editor of Education Next.