by Trip Gabriel, NY Times

In a vast congressional district of fluted mountain ranges, chili crops and oil and gas wells on the country’s southern border, New Mexico Democrats in November broke the Republican hold on a House seat that had endured for 37 years, except for a two-year break.

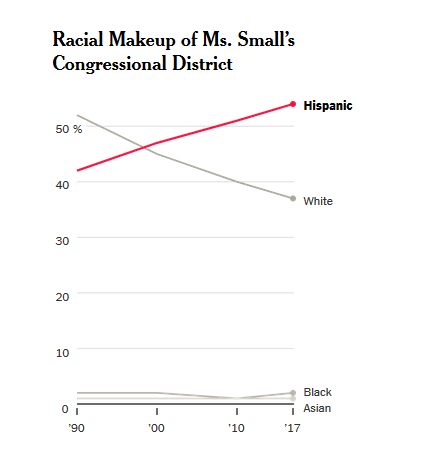

Xochitl Torres Small, a 34-year-old water rights lawyer, won by carefully calibrating her message as a problem-solver, like several other moderate Democrats who flipped House seats nationwide last year. Though the region is 55 percent Hispanic, she did not harp on President Trump’s border wall or his incitement of fears of immigrants bringing crime and drugs.

She did not need to.

“In New Mexico, we experience the positions of this president a little more intimately than a lot of people,” said Jeff Steinborn, a Democratic state lawmaker from Las Cruces. “The race baiting, divisive border politics has a very human face in our community.”

As Mr. Trump searches for ways out of the longest government shutdown on record, and struggles against some of his lowest approval ratings ever, he appears determined not to concede on his campaign promise of a border wall. Doing so could come at a political price with his supporters.

But at the same time, there is a toll to his party for his insistence on hundreds of miles of new border barriers.

Nowhere is that clearer than in the Southwest, where growing diversity and Mr. Trump’s demeaning rhetoric about Latino migrants are pulling parts of the region from the once-firm grip of Republicans.

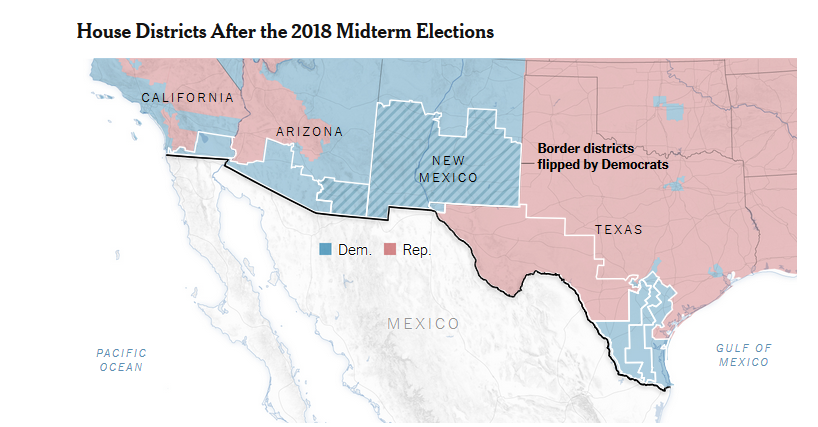

In addition to Ms. Torres Small’s district, Democrats flipped a House seat in the midterms on the southern border in Arizona and four seats in rapidly diversifying Orange County in Southern California.

In Arizona, Kyrsten Sinema, a Democrat, captured a Republican-held Senate seat, while in Texas the Democratic Senate nominee, Beto O’Rourke, came closer to winning a major statewide race than any other Democrat in 20 years. Ms. Sinema won 69 percent of Latino voters and Mr. O’Rourke 64 percent, according to exit polls.

Each of the nine House members whose districts touch the border from California to Texas opposes a wall as the wrong solution for border security.

“The irony of the wall is it works best the further you are from the border,” said Senator Martin Heinrich, Democrat of New Mexico, the state with the highest share of Hispanics.

While Mr. Heinrich glided to re-election in November, some Democrats from nearly all-white states farther north went down to defeat. “It was a huge issue in North Dakota and Montana in the Senate races,” Mr. Heinrich said.

“This constant picture painted by the president of this dangerous borderlands region is so incongruous with daily life,” he added.

Republican analysts play down the role of immigration and the border in the recent Democratic advances in the Southwest. Stan Barnes, a former Arizona state lawmaker and current Republican lobbyist in Phoenix, said the positions of Ms. Sinema on the border were nearly identical to those of her Trump-hugging opponent, Martha McSally.

“Kyrsten Sinema, you couldn’t tell the difference between her and Martha McSally on matters of the border,” he said. “She did not run as a Democrat, she ran as an independent or an Arizonan, and did not concede one bit of being tough on illegal immigration to Martha McSally.”

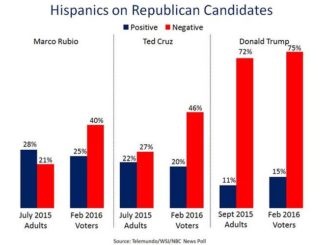

Demographers have long predicted the growing share of Latinos in Texas and Arizona would turn those Republican-leaning states a shade of purple or blue. Democrats’ expectations of awakening “the sleeping giant” of Latino voters have been repeatedly thwarted.

But 2018 may have moved them a step closer to the future. More than one in four Latino voters said they cast a ballot in a midterm election for the first time, versus 12 percent for whites, according to the Pew Research Center. In congressional races across the country, about 69 percent voted for the Democrat.

“Immigration is the big deal breaker in not voting Republican,” said Joseph Garcia, director of the Latino Public Policy Center at Arizona State University.

Because Latinos are much younger on average than whites, and many are just forming a partisan preference, Mr. Garcia predicted that Mr. Trump’s policies and language about immigrants would sour them on Republicans in federal elections for years to come.

“It wasn’t just the wall, it was the rhetoric over three years demonizing Latinos in general,” he said. “That has a longer-lasting effect than just this administration.”

“The die has been cast in that Arizona’s future is largely Latino,” he added, “and they’re all U.S. citizens because they were born here.” The median age of Latinos in Arizona is 26, and for non-Hispanic whites, 43.

To James Kolbe, a Republican who in the 1990s and 2000s represented the Arizona congressional seat that flipped in the midterms, south and east of Tucson, the president’s rhetoric about illegal immigrants was reminiscent of the white-hot anger he heard at town hall events in the mid-2000s. But that talk is out of date, he said, because the reality on the southern border is far different.

With illegal immigration near a 50-year low, more Mexicans are leaving the United States than entering. Meanwhile, there is a spike in families and children from Central America turning themselves in to border agents.

Critics of the Trump administration say the actual border crisis is one of its own making because it has failed to allocate resources to process asylum seekers and humanely house children and families.

In the race for Mr. Kolbe’s old district, which has swung between the parties, the losing Republican supported Mr. Trump’s wall, while the Democratic victor, Ann Kirkpatrick, opposed new border barriers and called for a path to citizenship for “Dreamers,” the immigrants brought to the United States illegally as children.

While the district’s overall population since 2000 has grown by 14.5 percent, its Latino population soared 53 percent, according to a New York Times analysis of census data.

Back in New Mexico, Ms. Torres Small won a narrow victory in the Second District thanks to a voter surge in Democratic-leaning Las Cruces, the state’s second-largest city.

Turnout in the city and surrounding Doña Ana County was up 4 percent over 2010, while in Lea County — a Republican stronghold — turnout fell more than 7 percent, starkly showing the contrast between Democratic and Republican enthusiasm, which many observers trace to Mr. Trump.

On Saturday, chants of “No wall! No wall!” broke out as Ms. Torres Small spoke at the local women’s march about the need to compromise with the president on the shutdown.

“We have to make sure that people who live on the border have a voice for what we want our border to look like,” Ms. Torres Small said, according to The Las Cruces Sun News.

Meanwhile, at a street market downtown where farmers sold honey and chili pepper wreaths, shoppers said they had no sense of a crisis on the border, which is 40 miles south and buffered by scrubland of juniper and yucca.

Last year the Border Patrol replaced 20 miles of low fencing meant to stop vehicles with a column-style barrier, 18 to 30 feet tall, which one shopper called a “Jurassic Park wall.”

“I really don’t think about it very much at all,” said Patricia Mihok, who was selling children’s books she had written about wildlife of the Chihuahuan Desert, which straddles the international border. She worried that a border wall would threaten migrating species.

Rory Richardson, 70, a retired airline pilot, called a wall a waste of money. He blamed the president for falsely accusing immigrants of crimes unsupported by statistics.

“He brings out the very worst in this society,” Mr. Richardson said. “He’s talking to the people who supported him from Day 1, that don’t care about the truth. They’ve made up their minds and don’t confuse me with the facts.”

But Henry Diaz, 85, a retired sheriff of Doña Ana County, who was strolling with his wife after a breakfast of huevos rancheros at Rosie’s Cafe, said a border wall was needed.

“Everybody has a fence around their house,” he said. “Why do you have that? You need the privacy.”

New Mexico, which last voted for a Republican for president in 2004, was once more of a political battleground than it is today. Democrats made sweeping gains in the midterms, winning not just the Second District but also the governor’s race and enlarging their majorities in the Legislature.

Last week, Democratic lawmakers in Santa Fe introduced bills to make New Mexico a “sanctuary state,” which would bar state agencies from helping federal immigration authorities who seek to deport undocumented immigrants.

“I think it’s important that New Mexico not help Donald Trump enact basically racist immigration policies,” Mr. Steinborn, the Las Cruces lawmaker, said.