by

In the nearly three months since elections dogged by accusations of voter suppression, state lawmakers across the country have either filed or pre-filed at least 230 bills that would expand access to the ballot for millions of Americans.

Bipartisan efforts aim to bring automatic voter registration, vote-by-mail, or the restoration of voting rights for ex-felons to more than 30 states.

Bills to increase voter access have outpaced election integrity bills, such as those that would require voter ID or proof of citizenship and would limit early voting, across the country this year, according to a count by New York University School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice. State lawmakers had introduced just 24 such bills.

High-profile questions over ballot access and the success of “pro-voter” ballot measures in November led to “an extraordinary groundswell of support for pro-voter reforms,” said Max Feldman, a counsel in the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program.

The midterms saw reports of voter registrations put on hold and rejected absentee ballots in Georgia and purges of names from voter rolls in Florida, Indiana and North Carolina. At the same time, voters in Michigan and Nevada approved automatic voter registration and voters in Maryland cleared the path for same-day registration.

Voting rights advocates are working to keep national attention on voting access issues, Feldman said, starting earlier this year with the introduction of the U.S. House’s first piece of legislation.

The Democratic bill would implement nationwide automatic voter registration, promote online voter registration, require same-day registration for federal elections, end aggressive voter purging, restore voting rights for ex-felons, make Election Day a national holiday and take redistricting power away from state legislatures and transfer it to independent commissions.

The bill is “not going anywhere in the Senate,” Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said in December. In an op-ed, the Kentucky Republican later called it “a naked attempt to change the rules of American politics to benefit one party.” But it set the tone for state lawmakers to push for significant voting changes, Feldman argues.

“State lawmakers were paying attention,” he said.

Expanding ballot access is not just being introduced in blue states. There are bills to establish automatic voter registration, same-day registration and the restoration of voting rights in purple and red states like Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, South Carolina and Texas.

After a decade of passing restrictive voting laws like voter ID, momentum is shifting toward passing small pieces of catch-up legislation to further modernize states’ voting systems, said Chapman Rackaway, a professor of political science at the University of West Georgia.

“It’s the pendulum swinging the other way,” Rackaway said.

“This year is definitely different,” Rackaway added, alluding to the sheer volume of bills and bipartisan support. “There are always some folks who are going to introduce legislation like this, but it’s not taken seriously. We’re seeing more states introduce these bills than we have before, and they’re more serious pieces of legislation.”

But there is still a deep divide across the country over the best approach to regulating elections. While this year may see some of the biggest expansions of voting rights in decades, many Republican lawmakers who still control most state legislatures will continue to fight against some measures they see as overreaching.

Hans von Spakovsky, a manager in the Election Law Reform Initiative at the right-leaning think tank Heritage Foundation, said there are hardened partisan lines around issues like automatic voter registration. Voting rights advocates, he said, “don’t have the momentum that they think they have.”

State fights over voting laws also will play out in court this year. In Wisconsin, Republicans in December passed new restrictions to early voting, before a Democratic governor took office. A federal judge quickly struck down those changes, however.

‘It’s Time’

With Democratic gains in state legislatures during the 2018 midterm elections, lawmakers in states such as New York — where Democrats now control the governorship and both houses — are poised to expand voter access.

New York has had some of the lowest voter turnout rates in the country. It didn’t break out of the bottom 10 during the 2018 midterms, at 45.2 percent, according to data compiled by the United States Elections Project.

Democrats in Albany, such as Charles Lavine, the chairman of the Assembly’s Election Law Committee, link the low turnout rates to the state’s voting laws — no early voting, no same-day registration, no voting by mail. For years, his colleagues in the Assembly have passed election bills, only to be thwarted by the Senate Republican majority, who refused to consider the legislation.

Requests for comment from several Republican senators were denied.

“We’ve passed these bills time and time again,” Lavine said. “We’ve been utterly frustrated with the Senate’s refusal to consider these measures. New York is deep blue, but the state Senate was deep red.”

As its first major legislative act, the new Democratic majority in the New York Senate on Jan. 14 passed a series of bills aimed at expanding voting rights.

The package included measures that would establish an early voting period, make federal and state primaries fall on the same day, allow 16- and 17-year-olds to pre-register to vote, and require the state Board of Elections to transfer registration information when voters move within the state.

The Senate also passed two amendments to the state constitution that would allow voting by mail and same-day registration. Both amendments would need to be approved by voters in a statewide referendum.

During the Jan. 14 floor debate over the legislation, Republicans in the chamber raised concerns about the speed with which the bills passed and the impact they might have on the integrity of elections. State Sen. Catharine Young, the Republican ranking member of the Senate Elections Committee, said these new requirements would impose costs on local governments.

“This is a huge unfunded mandate,” she told her fellow senators.

She also raised concerns that the package “is the first step to allow non-citizens to vote in New York.” Young did not respond to Stateline requests for an interview.

Despite these concerns, some Republicans voted for the measures, including early voting and same-day registration.

These measures previously passed in the state Assembly and are expected to be signed by Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

State Sen. Zellnor Myrie, the Democratic chairman of the Senate Elections Committee, told Stateline he plans to use his chairmanship to explore more voting legislation in the coming months, including automatic voter registration, electronic poll books, restoration for parolees and voting online.

Automatic Registration

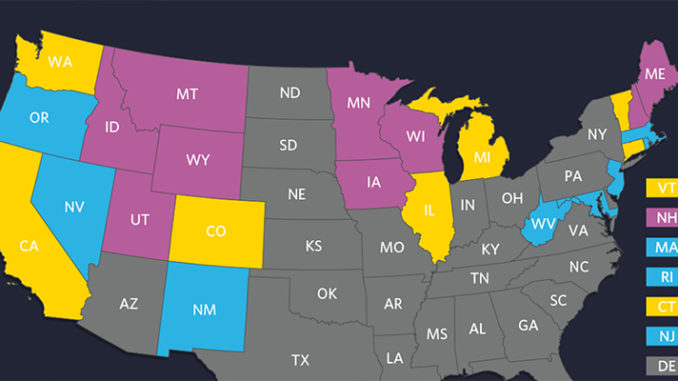

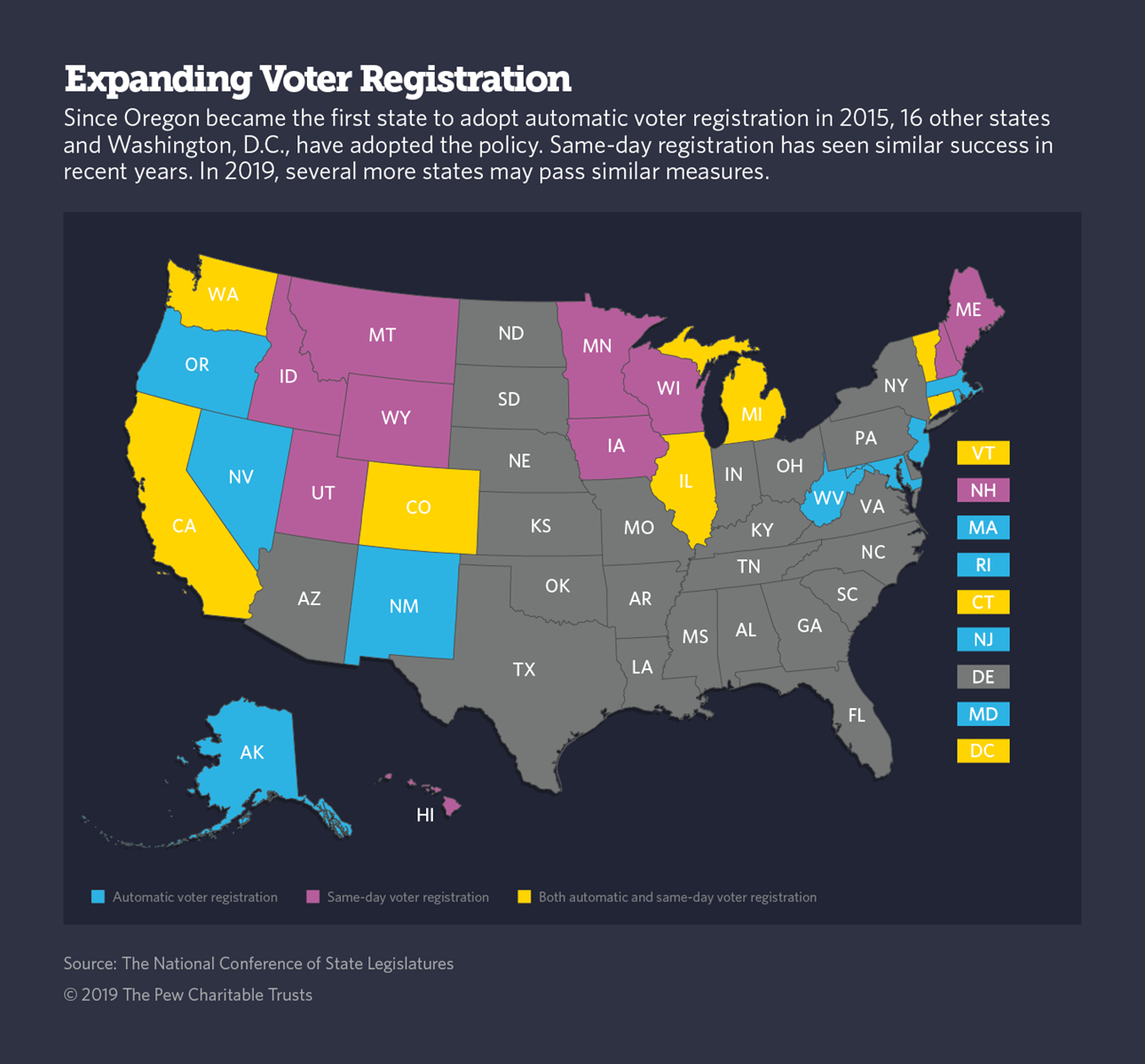

Automatic voter registration, under which residents have to opt out of becoming a registered voter when they visit a department of motor vehicles, has been implemented in 16 states and D.C. since 2015, while 17 states and D.C. now allow same-day registration.

Democratic lawmakers in Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, New Jersey and New Mexico, who control both the legislatures and the governorships, also have introduced packages that include automatic voter registration, same-day registration and early voting.

Minnesota, a state with some of the highest voter turnout in the country and where nearly 87 percent of eligible residents are registered, also is considering a package of election law changes, which includes automatic voter registration.

Secretary of State Steve Simon, a Democrat, said it would make the state’s system even easier for voters, even as some Republican lawmakers worry about the potential for voter fraud.

Rep. Jim Nash, the Republican assistant majority leader in the state House, said there is significant resistance in his caucus to adopting this measure.

“It may be a way to game the system if the person applying is an undocumented immigrant,” Nash said. “That’s a fairly prevalent concern in Republican circles.”

A package of election changes might also be a tough sell for Pennsylvania’s Democratic governor, Tom Wolf, who expressed interest late last year in similar measures but must contend with a Republican legislature that previously has opposed such efforts.

Restoring Felons’ Rights

While some Republicans have opposed measures to change voting law in legislatures across the country, it’s “too simplistic” to say that all Republicans oppose these reforms, said Chapman of the University of West Georgia.

Indeed, other voting measures are enjoying widespread bipartisan support. Both red and blue states are looking to lift barriers to the ballot for certain ex-felons.

In Iowa, Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds wants the state legislature to pass a constitutional amendment that would allow convicted felons to regain their voting rights.

“I believe Iowans recognize the power of redemption,” Reynolds said in her Jan. 15 Condition of the State address. “Let’s put this issue in their hands.”

Lawmakers in Minnesota, New Mexico and New Jersey have introduced legislation to restore voting rights for ex-felons.

In Minnesota, one of the bill’s co-authors, Republican state Rep. Nick Zerwas, said a political system that excludes people from being engaged in society doesn’t make sense.

“I don’t see this as a red or blue issue, but an issue of justice for people trying to put their lives back together,” he said in an interview.

The issue still falls along party lines in certain states. An effort to change the lifetime voting ban for felons in Virginia died in a Republican-controlled state Senate committee earlier this month.

Restoration of rights gained national attention in November, when Florida voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure that allows most ex-felons to vote, affecting 1.4 million residents. Already, people across the state are lining up at county elections offices to register.

But in December, newly elected Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis created some confusion when he told the Palm Beach Post that the measure should not go into effect until the state legislature passes “implementing language.” He opposed the ballot measure during the midterms.

Daniel Smith, a professor of political science at the University of Florida, said the measure was written to be “self-implementing” and did not need any further approval from the state legislature or DeSantis. But, he said, the legislature could try to pass abrogating language. Certainly, he said, there would be a lawsuit if that happens.

DeSantis’ office did not respond to a request for comment.

This worries Patti Brigham, president of the League of Women Voters of Florida, who cited examples of legislators in other states attempting to reverse approved ballot measures. In Missouri, lawmakers are attempting to block an anti-gerrymandering constitutional amendment that passed with more than 60 percent approval in November.

“It’s really mind-boggling that you have these state legislators that try to go against the will of voters,” Brigham said. “That’s why we have to be so watchful.”

Voter ID

In one of the dozen bills pre-filed in Texas this year that might pass, Republican lawmakers want to bolster the state’s voter ID law. The bill would allow election workers to make photocopies of a voter’s ID or take a picture of the voter if that worker suspects fraud. A federal judge in 2017 made the state soften its voter ID law.

In North Carolina, a measure requiring voters to show ID became law in December after the Republican-led legislature overrode Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto. Voters in Arkansas in November added a voter ID requirement to the state constitution.

While some Republican lawmakers have said voter ID laws strengthen election security and prevent voter fraud, critics argue those laws make it harder for minorities to vote and bolster unfounded fears of widespread fraud.

Ahead of the U.S. census in 2020, which will allow state lawmakers to redraw legislative boundaries, gerrymandering also has taken center stage.

Voters in Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, Ohio and Utah passed ballot measures to limit overly partisan redistricting in their states, implementing independent commissions.

But outstanding cases from Maryland, North Carolina and Virginia before the U.S. Supreme Court may be decided in the coming year, which could give lawmakers legal cover to gerrymander and give one party an advantage in their state for the next decade.

Gerrymandering’s effect was clear in Wisconsin in the 2018 midterms, for example. Despite Democrats receiving 190,000 more votes statewide, Republicans won 63 of the state’s 99 state Assembly seats.

And in Virginia, a federal panel of judges last week approved new district lines that weaken Republican-held legislative districts and strengthen potential Democrat-leaning districts.

This is Part One of the State of the States 2019 series.

Matt Vasilogambros writes about immigration and voting rights for Pew Trust’s Stateline. Before joining Pew, he was a writer and editor at The Atlantic, where he covered national politics and demographics.