More Latino students than ever are moving through high school to the doorstep of college, challenging higher education to adapt to a new demographic reality.

Striving to climb the social ladder, these young Americans are rapidly reshaping the marketplace for college recruiting. They are less affluent than others and less likely to have parents with college degrees.

And they are finding the gates to college open unevenly.

Hundreds of colleges and universities in recent years have become magnets for Latino students. Others, including the most prestigious, appear ill-equipped to find and serve a population that often needs significant support in the long journey from application to graduation. But educators say it is perilous to overlook a vast pool of potential students that will shape the nation’s economic future.

Two University of California campuses illustrate that divide.

Here at UC-Riverside in Southern California, 40 percent of the 20,000 undergraduates are Latino. They are earning bachelor’s degrees at a rate equal to white classmates and well above the national average. Most come from low-income homes and are among the first in their families to attend college. Many are children of immigrants.

Teresa Cortazo, a hotel housekeeping supervisor, fought back tears one fall day as she dropped off her daughter Emily at UC-Riverside. “She’s achieved what I haven’t,” the mother said. Her own formal education ended at secondary school in Mexico.

Stories like this abound on this campus in the arid Inland Empire.

“There’s just as many smart kids in the poor high schools as the rich high schools,” said UC-Riverside Chancellor Kim A. Wilcox. Too often, he said, those from poor families are overlooked. “We’ve got to give them that chance.”

The renowned UC flagship in Berkeley, on the other hand, has struggled to enroll a student body that reflects the state population. More than half of public schoolchildren in California are Latino, but the share at UC-Berkeley in 2016-2017 was 14 percent. That was 8 points lower than the share at rival UCLA, and lower than the other seven undergraduate campuses in the UC system.

“Berkeley is really an outlier in a way that concerns me,” UC-Berkeley Chancellor Carol T. Christ said. Within the next decade, she said, she wants the university to raise its Latino share to at least 25 percent.

Racial diversity in enrollment is a highly charged topic. Affirmative action faces a legal challenge in a federal lawsuit against Harvard University, and some Asian Americans criticize Christ’s goal as potentially discriminatory.

Under California law, public universities may not consider race or ethnicity in admissions decisions. However, Christ said UC-Berkeley can broaden its outreach to high schools, push harder for Latino students to accept admission offers and take other steps to help those with disadvantages feel welcome.

“Berkeley’s a fabulous university,” Christ said. “But not everybody experiences it that way. If you are a first-generation student, this is a hard place to navigate.”

The challenge extends well beyond California. The number of Latino students graduating from public high schools nationwide rose more than 60 percent over the past decade, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education estimates, and that surge is projected to continue through 2025. The total for most other groups, meanwhile, is stagnating.

Higher education leaders have long known of the Latino wave. Since the outset of the century, Latino undergraduate enrollment more than doubled, to 3 million in 2015. There are now 492 colleges and universities known as “Hispanic-serving institutions” because at least a quarter of their undergraduate populations are Hispanic. The total of such schools, according to the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, has doubled since 2005. The designation can help them obtain federal grants.

Most of the 492 are community colleges and regional universities. Experts say that reflects, in part, the preference of many Latino students to stay close to home.

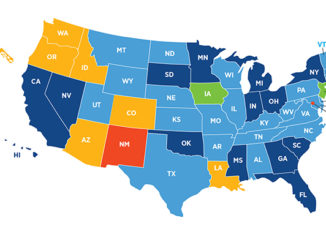

Some national colleges and universities are making inroads. Schools in the Midwest and the Northeast, where the college-age population is ebbing, have intensified recruiting in faster-growing regions of the South and West with a major Latino presence.

At MIT, 15 percent of undergraduates in 2016 were Latino. That was higher than at Duke, Princeton, Harvard and Yale universities.

“We look for the most talented students from everywhere,” said Stuart Schmill, MIT’s dean of admissions. He said the school puts “considerable effort” into recruiting students underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and math. “We are really pleased that we have such a thriving Latin American and Hispanic community.”

Among top-ranked schools, Hispanic-serving institutions are rare. There are four on the U.S. News & World Report list of top 100 national universities — all UC campuses. There are none on the U.S. News list of top 50 liberal arts colleges.

The magazine this year revised its ranking formula to give more credit for upward social mobility. UC-Riverside leaped 39 places to 85th among national universities. It had never before placed in the top 100.

Opened in 1954, the campus for decades was a modest UC outpost in Southern California’s citrus belt next to the Box Springs Mountains. In the 1990s, it went on a building boom coinciding with the growth of Riverside County. The vast county, stretching from greater Los Angeles to the Colorado River, is home to 2.4 million people.

Less exclusive in admissions than most other UC campuses, UC-Riverside draws a racial and ethnic mosaic. Asian Americans form the second-largest undergraduate bloc (34 percent), followed by white (12 percent) and black students (4 percent). Most of the rest are multiracial or international students.

Achievement gaps are minimal. The six-year graduation rate for Latino students is 73 percent, up 15 points compared with five years ago. The rate for white students is 72 percent. For black students, it is 75 percent, and for Asian Americans, 79 percent.

The national average is 60 percent — and for Latinos, 54 percent.

The typical Latino student has overcome multiple hurdles just to get here. Hundreds are undocumented immigrants. Others are children or grandchildren of immigrants. Nearly two-thirds qualify for Pell Grants. More than 80 percent would be among the first in their families to get a college degree.

Abrianna DeLay, 18, from Palmdale in Los Angeles County, traces roots to Mexico through her mother’s side of the family. “She’s the first one in our family to go to college,” said Regina DeLay, Abrianna’s mother. “So everything’s totally new to us.”

Mike DeLay, a fire captain for the U.S. Forest Service, was arranging his daughter’s loft one late September morning in the Pentland Hills Residence Hall. “Definitely proud,” he said. “Dropping her off is just one step. It’s a long road ahead.”

Joshua Mendez Arias, 18, said goodbye to his family near the school’s carillon bell tower. The clan had driven here from East Palo Alto, six hours away in the Bay Area. Arias plans to major in business and computer science. He said he came from a high school where students “all shared one common goal — going to college.”

Arias’s stepfather is from El Salvador. His mother, Ingrid Arias, who was wearing a UC-Riverside baseball cap, completed a few years of elementary school in Guatemala before coming to the United States and finding work in dry cleaning. “I persevered because I wanted a different life for him,” she said. “A future.”

Arias gave long hugs to her and his tearful 5-year-old sister.

Many Latino students feel a strong pull from family even after they arrive at college. Sometimes, that’s a hurdle to immersion in campus life.

Gabriel Pineda, 18, from San Diego County, joked after drop-off that his mother had sent “20 texts already.” He said he was drawn to UC-Riverside as a place where he could feel completely at home as a gay Latino.

“You can be anybody here and people wouldn’t care,” he said. “People don’t judge me.” He plans to major in theater, film and digital production and said he wants to make films that educate and empower. “Less hate,” he said. “Less hate crimes.”

What sets UC-Riverside apart, students and educators say, is a culture of support. Financial aid and peer mentoring are cornerstones. Professors take time to learn how to pronounce names. Latino activism, rooted in the Chicano movement of the 1960s and 1970s, runs deep here. There is an immigration lawyer on campus to help students.

Many administrators and faculty see echoes of their own lives in these students. Wilcox, whose family ran a grocery store, was a first-generation college student. So was the provost, Cynthia K. Larive, whose father was a gold miner.

Faculty say it’s inspiring to teach students with high potential who might lack the academic advantages of those from affluent high schools.

“We have a lot more to overcome in four to five years in terms of preparing them and getting them up to speed,” said Guillermo Aguilar, chair of mechanical engineering. “But by the time they graduate, they’re as competitive as any Berkeley or UCLA graduate.”

Aguilar, a native of Mexico City and a naturalized U.S. citizen, is one of relatively few Latino professors here. A major obstacle to diversifying the faculty is the scarcity of Latino students in doctoral programs.

By the time they get a bachelor’s degree, Aguilar said, many Latinos face economic pressures that drive them away from graduate school. “They need the money now,” he said, adding parents will often ask them: “So when are you finally going to get a real job?”

In a way, that question shows progress. Census data show Latino adults are much less likely than others to have any college degree. Schools like UC-Riverside aim to close that gap.

Late one afternoon, thousands of new students gathered on a sun-splashed lawn for fall convocation. Dylan Rodríguez, a media and cultural studies professor, told them that in their diversity, they embodied the university’s public mission.

“You must allow who you are, and where you are from, to form an integral part of why you are here,” he said. When the university opened decades ago, Rodríguez told them, few if any of the faculty or students “looked anything like me or many of you.”