by Taylor Swaak, The74

California posted a near all-time high graduation rate — 83 percent for the Class of 2018 — but the rate of students eligible to apply for state universities hasn’t budged, according to data released last week by the California Department of Education.

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson said in a news release that “much work needs to be done to make certain all students graduate and to close the continuing achievement gaps between student groups.”

The data are typically published in early spring, but the department wanted to ensure the latest information would be ready for next month’s update to the California School Dashboard, the state’s new accountability system. The dashboard’s update will include 2018 data on a revamped, more user-friendly platform that will be viewable on mobile devices and translated into Spanish.

Here are six main takeaways from the new state data:

1 Graduation rates are up …

The Class of 2018’s graduation rate was 83 percent, up from 82.7 percent for the Class of 2017 and considerably higher than the 74.7 percent rate California posted in 2010.

In Los Angeles, the graduation rate for the state’s largest school district was 76.6 percent for 2018, up from 76.1 percent in 2017, according to the state data.

Graduation rates across California pre-2017 were slightly higher because they were calculated differently. They had to be adjusted last year after an audit by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Inspector General found California did not calculate its rates according to federal requirements.

Federal Audit Finds California Inflated Its High School Graduation Rate by 2%

The nationwide high school graduation rate for 2016, the latest data available, was an all-time high — 84 percent.

2 … but only slightly for English learners, poor, black and Latino students.

While graduation rates for most California student groups grew — especially for foster youth — minority groups only made small inroads:

● Black students: A 0.2 percentage point increase in 2018, from 73.1 percent to 73.3 percent.

● Hispanic or Latino students: A 0.3 point increase, from 80.3 percent to 80.6 percent.

● English language learners: A 0.8 point increase, from 67.1 percent to 67.9 percent.

● Poor students: A 0.8 point increase, from 78.8 percent to 79.6 percent.

Foster youth graduation rates reached 53.1 percent in 2017-18, compared to 50.8 percent the year prior.

White students, however, lost ground, dropping to 87 percent last year from 87.3 percent in 2016-17.

3 There is no change from last year in college readiness.

Nearly half — 49.9 percent — of the Class of 2018 met admission requirements for the University of California and/or the California State University systems — the same as in 2017.

The state reported that for Los Angeles Unified students, 61.9 percent met those requirements, up from 59.8 percent in 2016-17.

L.A. Unified’s school board in June passed a resolution to get 100 percent of students “prepared for college, career and life” by 2023. To boost accountability, it will announce two graduation rates moving forward: the percentage of students who graduated meeting state standards, and the percentage of how many were eligible to apply to state schools

Schools in Los Angeles Will Now Report Two Graduation Rates to Reveal How Many Students Are Actually Eligible for State Universities

“We’re raising the bar, being aspirational, and believing on what we can do,” board President Mónica García said at the time.

College preparedness struggles in California mirror a nationwide dilemma. A 2017 survey revealed only half of U.S. seniors think their high schools have prepped them for a post-secondary education. Another analysis of more than 900 U.S. colleges found that about 23 percent of them had more than half of their incoming students enrolled in at least one remedial course.

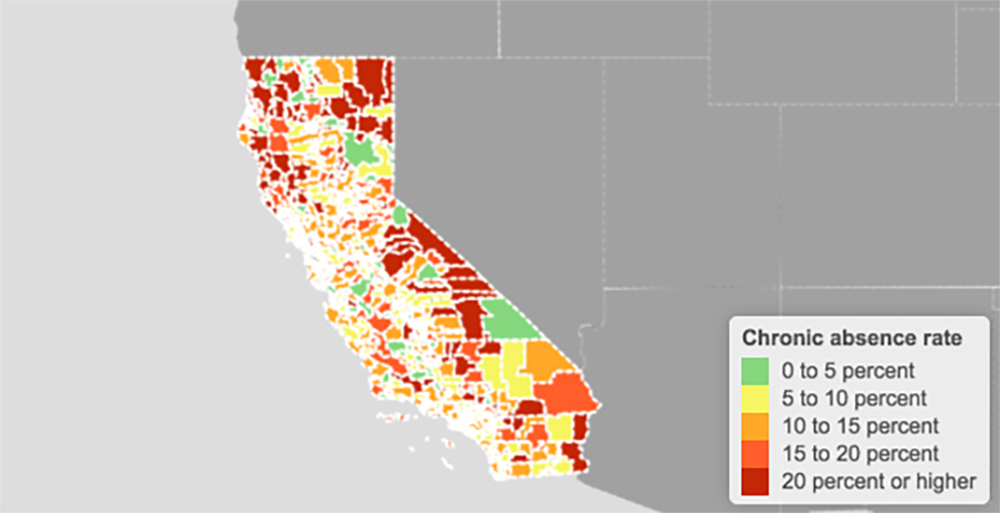

4 Chronic absences got worse — for nearly every subgroup.

During the 2017-18 year, 11.1 percent of California’s students were “chronically absent,” which the state defines as missing 10 percent, or about 18 days, of the school year. This is up slightly from 10.8 percent in 2016-17 — and tallies to 16,000 more students in 2018 who were chronically out of school.

The state next month is adding chronic absence data to its California School Dashboard, but only for students through eighth grade. It began collecting and reporting chronic absence data from schools and districts for all grades in 2016-17.

California’s reported chronic absence rate is hard to compare to the U.S. average because national data, collected by the Office for Civil Rights, defines chronically absent students as those missing 15 or more days of school. The U.S. average for 2015-16 — the most recent year for which nationwide data is available — was about 16 percent. California was below the national average at 12.2 percent.

L.A. Unified had an 11.9 percent chronic absence rate in 2017-18, a slight bump from 11.7 percent in 2016-17, according to the state. Of all ethnicities, black students in the district have the highest rate of chronic absences, at 20.9 percent. For all students districtwide, 1 in 4 kindergartners is also chronically absent.

The effects on academics are calamitous when students miss school: Children who are chronically absent in preschool, kindergarten and first grade, for example, are much less likely to read at grade level by third grade, a report last year found.

And absences are increasingly expensive. In 2016-17, L.A. Unified lost about $630 million in revenues from students not coming to school. (The state’s school districts receive federal funding based on average daily attendance, rather than enrollment.) Superintendent Austin Beutner said in May that if L.A. Unified can turn 8,000 to 10,000 kids into better attenders, “they’ll learn, and absenteeism matters to the whole classroom because the revenues come back.”

5 Despite higher graduation rates, enrollments are down, and dropouts are up.

Increases in graduation rates contrast with declines in enrollment and growing dropout rates.

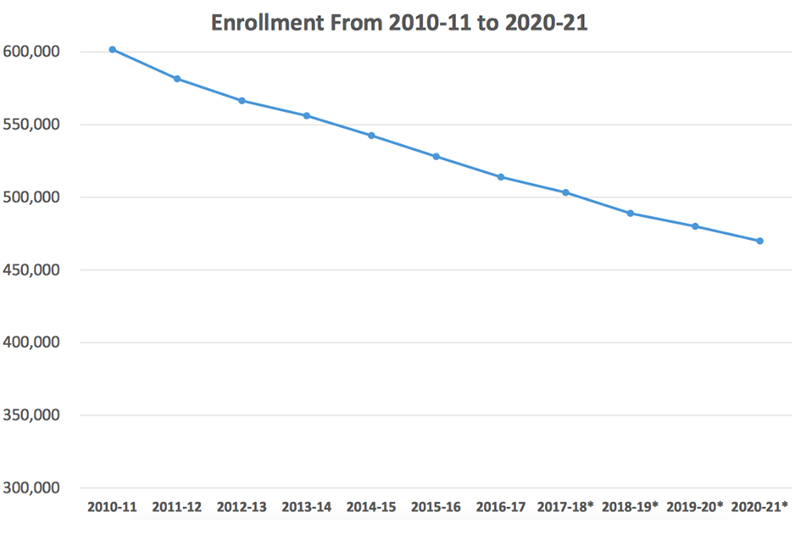

In California, student enrollment has decreased every year in the past five years except for 2016-17, according to state data.

At the same time, its dropout rates are rising. The number of 2018 dropouts statewide totaled 48,453 — up nearly 3,500 students from 2017. The dropout rate as a result rose from 9.1 percent to 9.6 percent. The highest rates were reported for foster, homeless and American Indian or Alaska native students, according to the new data.

Nationwide, the U.S. high school dropout rate was 6 percent in 2016.

L.A. Unified is similarly losing thousands of students each year; it’s lost more than 24,000 students in the last two years. Its high school dropout rate as of 2016-17 was 12.2 percent, according to Open Data.

The student enrollment loss annually is “the equivalent of closing 12 major high schools,” board Vice President Nick Melvoin said earlier this year. “Are we sending out RIF (reduction in force) notices and pink slips?”

6 Traditional public schools have higher graduation rates than charters.

When only considering traditional public schools, the state graduation rate hikes to 91.7 percent. “Alternative” schools such as juvenile court and county-run special education schools bring down the overall state rate.

Comparatively, independent charter schools have a graduation rate of 84.2 percent, the state data reported.

Taylor Swaak is an editorial fellow at The 74. @tswaak27