by Jacques Leslie

It is a tantalizing feature of California politics that if more of its citizens performed the simple act of voting, the state’s already substantial national influence would grow exponentially. That’s particularly true this year, when election turnout will largely determine whether California helps hand control of the U.S. House of Representatives to Democrats.

Unlike presidential elections, which typically generate enough excitement to boost voting levels, midterm elections are fundamentally battles over turnout. In the last midterm, in 2014, only about a third of eligible California voters went to the trouble. Among the 50 states and District of Columbia, California ranked 43rd in percentage of voting citizens, according to the Pew Research Center. Latinos, millennials, African Americans, Asian Americans and unmarried women fell short even of the state’s paltry average.

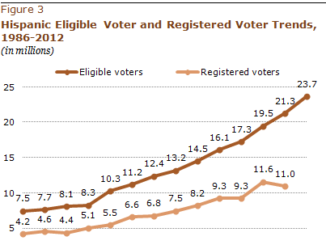

Imagine that this Nov. 6, Latinos, who constitute California’s largest ethnic group, merely voted in proportion to their percentage of the state’s population: The increase would add more than 3 million votes to the ballot boxes. According to David Mermin, a Democratic pollster at Lake Research Partners, the upsurge almost certainly would favor Democrats — most Latinos register as Democrats — and it would be enough to unseat at least five of the 14 Republicans among the state’s 53 House members. As it happens, five is precisely the number of seats that political handicappers calculate California must flip to put Democrats on track to capture the House.

If, on top of that, you assume equivalent proportional turnout by African Americans, Asian Americans, millennials and unmarried women, only a few congressional Republicans would likely survive. All by itself, California would probably flip more than a third of the 23 seats Democrats need to seize the House. Turnout that big probably also would hand Democrats two-thirds supermajorities in the state Senate and Assembly, making the passage of key legislation on healthcare, housing, education, climate change and clean water more likely.

A boost in Latino voting nationally strengthens the clout of all Latinos in Congress, and in California would deliver a robust rejoinder to President Trump’s defamatory attacks on Mexicans and immigrants. San Francisco’s Rep. Nancy Pelosi would almost certainly retake the House speaker’s office, and Rep. Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank) would become the House Intelligence Committee chair, enabling him at last to launch a serious investigation into Trump’s suspect Russia connections. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles), a frequent Trump irritant, probably would take over the House Finance Committee.

Many pollsters think a Democratic “wave” election is possible in 2018, but achieving that is far from certain.

Consider, for example, the San Joaquin Valley’s 21st Congressional District, one of the nation’s poorest districts. Hillary Clinton won it by 15.5 percentage points in 2016, and 71% of its population is Latino — it ought to be a Democratic mainstay. But for the last six years. Rep. David Valadao, a Republican ex-dairy farmer, has won reelection easily. Valadao leads in polls again this year, partly because he has tried “to gain some distance from Trump,” in this newspaper’s words, on immigration, and partly because he is reputed to excel in constituent services. But the district’s “lean Republican” rating from the nonpartisan Cook Political Report also owes a lot to projected turnout, which prognosticator FiveThirtyEight estimates will be just 26.1%

One reason few Latinos vote is that the Democrats’ get-out-the-vote infrastructure often has left them out. Even in heavily Latino and Democratic California, in past elections no campaign officials have called them; no volunteers have knocked on their doors. With the party’s two main national campaign organizations now both led by Latinos, Tom Perez and Ben Ray Luján, Latino districts are finally getting more attention.

The difficulty of getting to the polls also dampens turnout. A farmworker paid a minimum wage must think hard about passing up a few hours’ income to cast a vote. The ballot may be confusing and the issues unfamiliar. It can’t help that, according to an ACLU lawsuit, mail-in ballots from Latino (and Asian American) voters are routinely invalidated at higher rates than those cast by other voters.

Trump’s relentless attacks on immigrants and Latinos may also intimidate some Latino voters, or at least disenchant them with politics — why have anything to do with a government that demeans them? But for all the Latinos pushed away by Trump’s insults, perhaps more have been motivated to oppose the GOP. “We’re seeing an explosion of enthusiasm in our community,” Cristóbal J. Alex, president of the Latino Victory Project, whose mission is building progressive Latino political power, told me.

With 12 days to go in the campaign, it’s not too late for citizens throughout California to help increase turnout. Make sure that potential voters among family members and friends understand the choices and know how to vote by mail or in person. On election day, make sure voters without transportation (such as millennials and seniors) know that Lyft and Uber are offering free or discounted rides to the polls, or drive voters there yourself.

Elections are often touted as the most important of their era, but this time the assertion is true: The 2018 election will determine whether Congress is able to check the descent into authoritarianism that the most reckless and corrupt president in the nation’s history has launched. California, the self-proclaimed center of resistance to Trump, ought to lead the way.

Jacques Leslie is a LA Times regular contributing opinion writer and frequent contributor to NY Times opinion pages & Yale Environment 360. Author of Deep Water & The Mark.