The Pew Charitable Trusts

Wearing a red-white-and-blue blouse with a sticker declaring “I’m so gonna vote,” Kassie Phebillo sits behind a table here at the University of Texas, dispensing information about the Nov. 6 midterm election. Nearby, scores of students line up to cast their ballots on the opening day of early voting.

The display of political energy contrasts with Texas’ long record of lackluster voter turnout. In the last midterm election in 2014, Texas’ 28.9 percent turnout was less than 1 percentage point higher than dead-last Indiana’s, according to the United States Elections Project, which estimates voter turnout based on reports from state election offices.

A large percentage of Texans are young people and Latinos, two groups of people who are less likely to vote than the general population. Critics say a voter ID requirement, which went into effect in 2013 and has survived years of legal challenges, also has played a role. And more than two decades of Republican dominance has eroded resources for the rival Democrats and stifled competition.

“People haven’t participated because they feel like their vote didn’t make a difference,” said Grace Chimene of Austin, president of the League of Women Voters of Texas.

But this year’s election may be different: As in other states, there have been long lines at early voting sites throughout Texas, raising the potential for an upturn in the sluggish voting patterns that typically characterize midterm elections — especially here.

In Texas’ 30 largest counties, 2.4 million people cast ballots in the first days of early voting, surpassing the combined totals for early voting and mail-in balloting in the 2014 midterm, the United States Elections Project found.

“There’s a guy named Donald Trump and either you love him, or you hate him, but he inflames passion, and when people are passionate, they’re going to vote,” said Michael McDonald, who directs the project. “It’s just another manifestation of Trump. He’s affecting politics and now he’s affecting turnout in the election.”

“We’ve never seen this level of engagement this early in the early voting period,” McDonald said. “Something special is happening out there right now.”

The Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration and the president’s frequent use of heated language to describe immigrants from Mexico and Central America appears to be energizing Latino voters in Texas and elsewhere.

Voto Latino, a national nonprofit that aims to propel younger Latinos into the political process, has registered more than 200,000 voters this election cycle, including 52,000 in Texas.

Jessica Reeves of Austin, the group’s chief operating officer, said Latinos feel “a real need to push back against negative rhetoric.”

A surprisingly competitive U.S. Senate race also is pumping up participation in Texas. Democratic U.S. Rep. Beto O’Rourke has raised a staggering $70 million in his bid to unseat Republican Sen. Ted Cruz, who has raised about $33 million.

Turnout Traditions

Hard-fought congressional contests in Indiana, Minnesota and Nevada have driven early-voting turnout to presidential-election levels in those states, as have close gubernatorial races in Florida and Georgia.

But in some states, high voter turnout is nothing out of the ordinary.

In 2014, nearly 59 percent of Maine voters turned out to vote, which was tops in the nation. Analysts say Maine and other states with consistently high voter-turnout rates, such as Minnesota and Wisconsin, typically have a better-educated electorate as well as fewer impediments between the voter and the ballot box.

Maine’s population of 1.3 million is dominated by older white voters, who tend to vote in greater numbers. People who are retired have more time to vote, and they also are aggressively protective of vital economic lifelines such as Social Security and Medicare.

Amy Fried, who chairs the political science department at the University of Maine, said Mainers frequently interact at town meetings and have fiercely defended their stake in government for more than two decades.

In 2011, when Maine leaders enacted legislation to end the state’s 38-year-old practice of allowing registration on Election Day, residents rebelled and voted to overturn the law.

“They are just very involved,” Fried said.

In Texas, groups are trying to create a similar dynamic among Latinos and young people through aggressive voter registration efforts. Overall turnout for the 2014 midterms was 42 percent and the rate among Latinos was only 27 percent, census data shows.

Domingo Garcia, a Dallas lawyer and the president of LULAC, the nation’s oldest Latino civil rights organization, said Trump’s policies have propelled mobilization efforts. Garcia predicted “huge numbers” of first-time Hispanic voters in states such as Arizona, Florida, Nevada and Texas.

“I think the election is really a referendum about Trump in the Latino community,” Garcia said. “He is probably the most despised president in my lifetime.”

Nationwide, two-thirds of Hispanics polled by the Pew Research Center in June said they disapproved of Trump. (The Pew Charitable Trusts funds both the center and Stateline.) Still, a recent University of Texas poll showed that Latino voters in that state were not as enthusiastic about voting this year as were whites.

Young people also may vote in higher than normal numbers this year, many motivated by the mass shooting that killed 17 students and staff members at a high school in Parkland, Florida, in February.

Thirty-four percent of people in that age group are “extremely likely to vote,” which would be a historic high for a midterm election, according to a recent poll by the Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts University. The highest midterm turnout for that group was 31.7 percent in 1982.

“I think it’s important if I want to change anything,” said Christine Garner, an 18-year-old University of Texas freshman who cast her ballot on the first day of early voting. “And I think there definitely needs to be more young people voting, especially when our representation is so much older than us.”

Pushing Back

Voting rights activists in Texas and elsewhere also are pushing back against what they perceive as Republican efforts to suppress voting among young people and minorities, who tend to favor Democrats.

A lawsuit by students at historically black Prairie View A&M University in Waller County charged that early-voting restrictions were suppressing the voting rights of African-Americans. This month, officials in the rural southeast Texas county responded by expanding voting hours and opening a new polling place.

Similarly, Hays County commissioners in central Texas agreed to expand voting hours at Texas State University in San Marcos after the Texas Civil Rights Project threatened a lawsuit on behalf of two students.

Zenén Pérez, a spokesman for the project, said myriad flaws in Texas’ voting system — from antiquated voting machines to backward registration policies — constitute “death by a thousand cuts.”

“It’s not that there’s one issue of suppression,” he said, “but there are all these little things that add up to basically a culture and a blanket of suppression across the state that makes it difficult for people to go vote.”

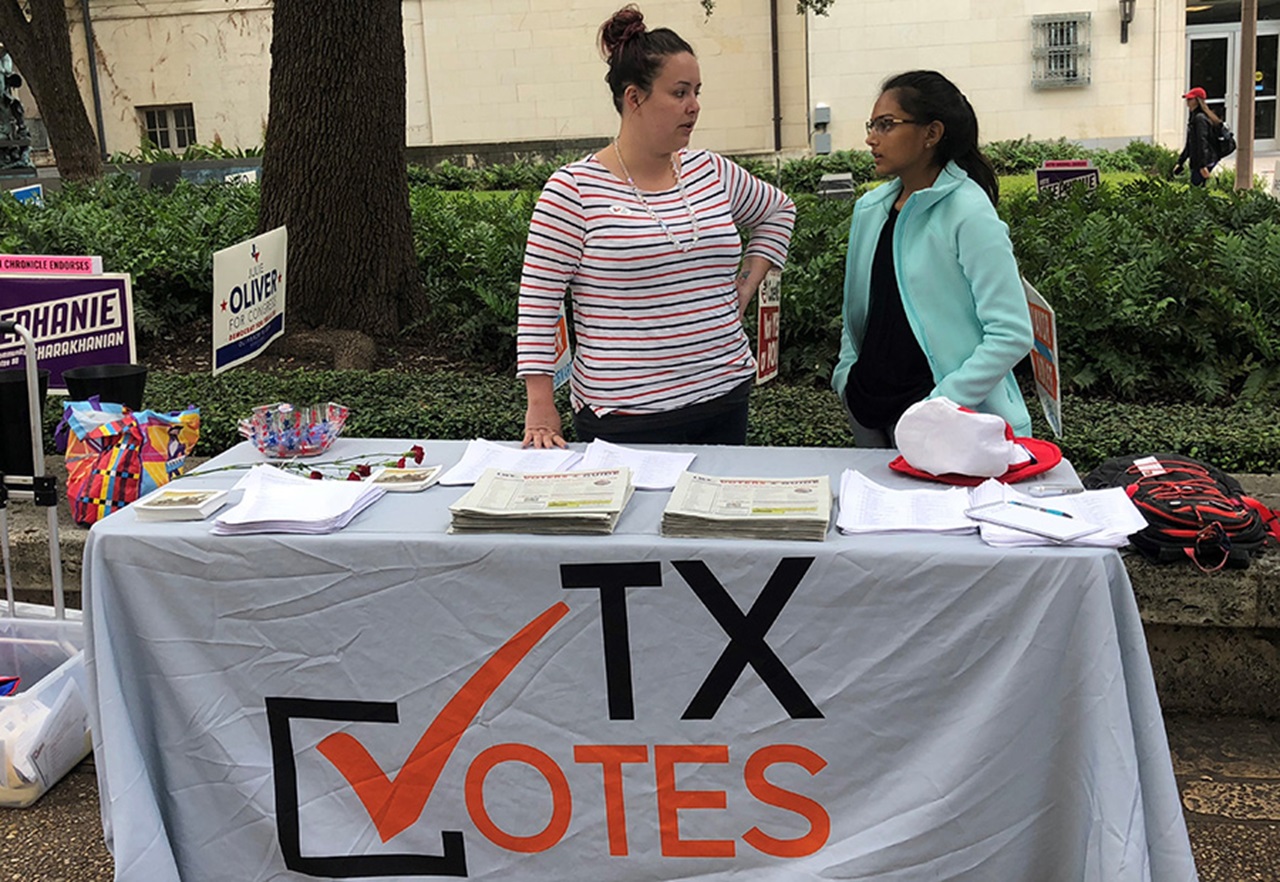

From behind her information table here at UT Austin, Kassie Phebillo is doing her part to rally young people toward the voting booth. A newly married 29-year-old who is pursuing a doctorate in communications studies, she’s the program coordinator for TX Votes, a student organization committed to increasing voter awareness on campus.

With a “TX Votes” banner adorning the front of the table, Phebillo and other volunteers explain the process to anyone who stops to inquire. “Thanks for voting,” she shouts to a student who is just leaving the campus polling place with an “I Voted Early” sticker on his shirt.

Earlier this year, volunteers set up tables in more than 250 classrooms to register students. Now that registration has closed, their core duty is advising students on how and where to vote.

Standing under an overcast sky on the first day of early voting, Phebillo is joined by the TX Votes interim president, Maya Patel, a 20-year-old chemistry major whose parents are scientists.

Patel’s mother is from Kenya. Her father was born in Tanzania and grew up in India and London. She learned the importance of civic involvement when she helped her father study for his citizenship test.

“I’m passionate about this stuff because my parents are immigrants to this country,” she said. “And they didn’t always have the right to vote.”