by Beth Hawkins, The74

In the nation’s most economically segregated city, an innovative new approach to school integration designed to address poverty, trauma, and parental choice is working.

J.T. Brackenridge Elementary sits on the eastern edge of zip code 78207, which is the way people refer to the Mexican-American community that surrounds the school. Located just west of downtown San Antonio, the neighborhood is as rich with art and history and culture as the rest of the city. Yet it’s a world apart.

To travel to or from the school is to take a compressed trip through time. Head east, and every few hundred feet Guadalupe Street presents a different line of demarcation — each a visual reminder of who lived here and what life was like during those respective eras of human habitation.

There’s Alazan Creek, one of the spring-fed waterways that drew nomadic tribes and Spanish conquistadors, now a concrete culvert lined, not with public art, like the city’s iconic Riverwalk, but with untamed scrub. After Guadalupe crosses the river, the road widens and rises, going over busy train tracks that conveyed the raw materials that were used to build the modern metropolis, and then the scrapyards to which spent rebar and steel are returned, to be reforged as the city’s next iteration.

The final boundary is an elevated interstate, a current-day conduit in the sky that bisects the cramped 25-foot lots of the 78207 from the lofts, the leafy, art-filled riverside promenades, the tail-to-snout eateries, and the brewpubs of the city’s prosperous core.

In this daily school commute up and down Guadalupe Street, parents and students are presented with a vivid illustration of their stark reality: By virtually any statistical measure, San Antonio is the most economically segregated city in the United States. Its poorest neighborhood, the 78207, is located a scant few miles from the epicenter of the third-fastest-growing economy in the country. But as the city as a whole thrives, the residents on the West Side are all but locked out of the boom.

Into this divided landscape three years ago came a new schools chief, Pedro Martinez, with a mandate to break down the centuries-old economic isolation that has its heart in the 78207.

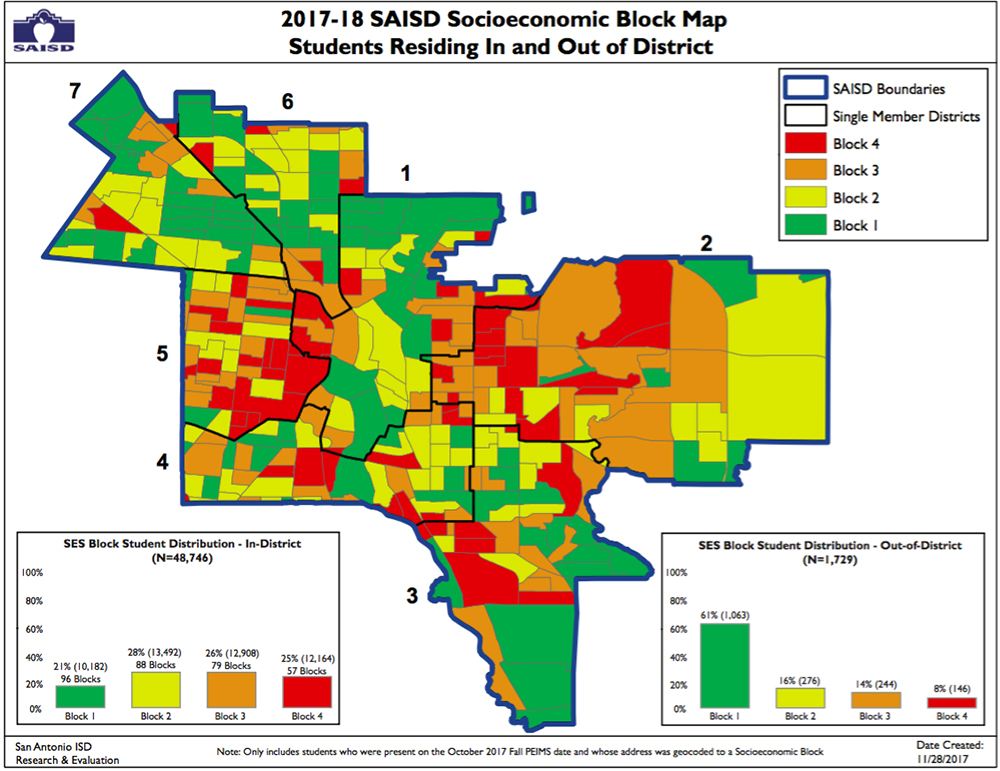

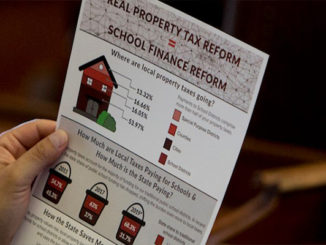

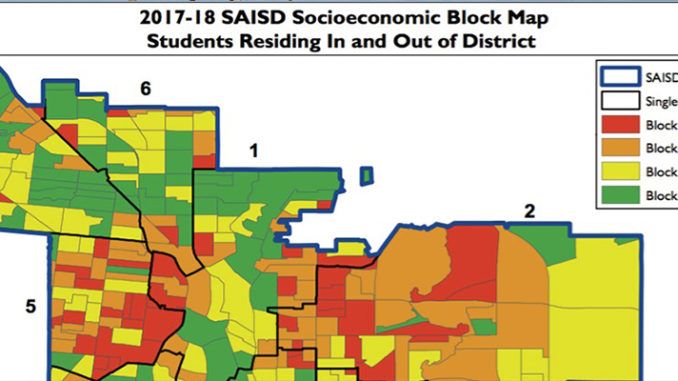

In response, Martinez launched one of America’s most innovative and data-informed school integration experiments. He started with a novel approach that yielded eye-popping information: Using family income data, he created a map showing the depth of poverty on each city block and in every school in the San Antonio Independent School District — a color-coded street guide comprised of granular details unheard of in education. And then he started integrating schools, not by race — 91 percent of his students are Latino and more than 6 percent are black — but by income, factoring in a spectrum of additional elements such as parents’ education levels and homelessness.

To achieve the kind of integration he was looking for, he would first have to better understand the gradations of poverty in each and every one of his schools, what kinds of supports do those student populations require, and then find a way to woo affluent families from other parts of the city into San Antonio ISD schools to disrupt these concentrations of unmet need. Martinez’s strategy: Open new “schools of choice” with sought-after curricular models, like Montessori and dual language, and set aside a share of seats for students from neighboring, more prosperous school districts, who would then sit next to a mix of students from San Antonio ISD, where 93 percent of kids qualify for free and reduced-price lunch.

Only a few years into the experiment, the effort has reshaped the educational landscape, and redefined the aspirations of its students and educators. The district’s diverse-by-design schools now have long lists of well-to-do families waiting for a seat to open up alongside students from working-class households and destitute neighborhoods. Families from the affluent communities on the city’s north and northwest sides are indeed now eagerly applying to share classrooms with families from the 78207.

Student learning has accelerated — in both the new, marquee programs and existing schools.

When Texas released its 2017-18 school performance scores last month, San Antonio ISD, with its 50,000 students and 90 schools, was named one of the fastest-improving districts in the state. The system as a whole had risen from the equivalent of an F rating to a C in just the past three years. Thirty-four of its schools earned the state’s “distinction” designation.

The number of San Antonio ISD schools that would have landed on the state’s “improvement required” list using 2018 criteria fell by half. Using the same calculus, the number of students enrolled in a low-performing school plummeted from 47 percent to 16 percent, the largest decrease among urban districts in the state.

With arguably the nation’s most radical school integration experiment reaping early wins, what Martinez says he needs most now is time — to get his still-disadvantaged schools from a C to an A, to change beliefs at all levels about what success looks like, and to stave off a gathering storm of opposition from those who disagree with his maverick approach.

National experts on school improvement are buzzing about Martinez’ work. But if he is to win over his detractors — and to reach the most profoundly destitute children within a larger community marked by poverty — he needs the same sense of excitement his work is garnering outside San Antonio to catch hold in his own segregated backyard.

WATCH — 74 Documentary: Inside San Antonio ISD’s school integration efforts:

Chapter 1: A boy from the barrio takes charge

Martinez is himself an immigrant from Mexico and a first-generation college-graduate success story. Soft-spoken and trained in finance — not as a teacher — he was a curious hire back in 2015 for the south Texas district.

San Antonio ISD is one of 17 school districts within the city limits, but its blanket poverty is no accident. The district’s boundaries were drawn decades ago to neatly follow the 1940s-era red-lined maps segregating blacks and Latinos into what is now an urban core. By contrast, the district located to the immediate north, Alamo Heights, has a poverty rate of 20 percent.

San Antonio ISD’s school board president, Patti Radle, has lived and worked in the 78207 — the district’s most impoverished neighborhood — for nearly half a century. A former J.T. Brackenridge teacher and community activist, she believed Martinez, like her, would see her neighbors’ pride and resilience, and not fall victim to what she calls “the pobrecito” — “poor thing” — phenomenon.

Radle listened to Martinez describe his family being forced to move every time their landlord figured out how many people were stuffed into their tiny apartment. She became convinced he understood the weight of students’ challenges, as well as the dangers of well-intended but misguided educators trying to protect them from rigorous academic material.

Martinez believed the neighborhood kids could succeed on par with their wealthy peers, just as he had done, and wouldn’t settle for less, she says.

“His attitude and his insight seemed outstanding,” she said.

She and her fellow board members told Martinez his job was nothing less than to create a school system that would serve as a model for big-city districts throughout the nation.

Never mind that these are the marching orders every urban school board chair gives every new superintendent — as the product of a similar community Martinez didn’t hear the directive as a rhetorical one. Neither of his parents made it past second grade, and both worked long hours to feed their 10 kids. At 16, Martinez went to work, too, to help support the family. He knew what creating a generation of college graduates eager to come home to live and work would mean for the 78207.

But knowing that nearly every student in the district was low income told Martinez only the size of the problem, not anything useful in terms of addressing it. In search of better information than what school districts traditionally compile, he turned to census data to create the color-coded map showing the wide variation of levels of poverty from one school to another.

After that, Martinez rebooted dozens of schools, reorganizing them around the kinds of programming — Montessori, dual language, gifted and talented — that families in wealthy communities paid private school tuition for. He recruited master teachers and pushed existing ones to retrain. Lacking the money of neighboring districts, he tapped civic organizations and philanthropies to pitch in.

And he did it fast: “We had to do something completely different,” he says, “knowing we can’t say to the kids, ‘Hey, can you stay home for a couple of years while we retool?’”

Fast-forward three years. Martinez has opened an eye-popping 31 schools of choice. Families — some of them affluent parents who previously didn’t give the district a thought — are clamoring to get their children in. Using what he now knew about the extreme poverty of some of his families, Martinez’s team created a sophisticated lottery system that carves out a percentage of those seats for the neediest students.

Philanthropy is writing big checks. The number of high school graduates going not just to college, but to selective colleges has soared. And Martinez has made sure to build cultural bridges to enable his graduates, many of whom had never before left Texas, to succeed there. In 2017, for example, he organized a road trip to Middlebury College in Vermont so the families of four San Antonio ISD students got the chance to settle their kids in at the elite liberal arts school, while catching a glimpse of what life is like in such an unknown setting.

The education world took note. In February, the Center on Reinventing Public Education brought dozens of leaders of cities that are home to large, struggling school districts to San Antonio to tour the new schools and to hear how Martinez managed to raise the bar so fast — and on a shoestring.

The center’s director, Robin Lake, credits Martinez’s willingness to listen to what the community wanted and to build first on its strengths for the quick buy-in he got. “He really took the time to hear about what was missing in kids’ educations,” she says, and to learn what would empower teachers.

“Going barrelling forth with a top-down solution the community isn’t going to feel good about is the past,” Lake adds, referring to a common criticism of some education reform efforts. “Listening to the community and creating the things they want is the work of the future.”

It appeared Martinez was well on his way to fulfilling his marching orders. But change agents have a way of attracting headwinds.

Last winter, the 48-year-old schools chief announced a plan to invite a charter school network to take over a struggling elementary school slated at that point for closure by the state. Almost overnight, the San Antonio Alliance of Teachers and Support Personnel declared war. The union filed a lawsuit. Critics vowed to oust the school board that hired Martinez. Posters appeared on telephone poles with the hashtag #byepedro.

Now, a new challenge looms. Can Radle and her school board colleagues stand firm, mustering enough support for Martinez’s efforts to continue to spread beyond the impoverished but gentrifying and historic parts of the district where San Antonio ISD’s most successful new schools have opened? Can families have the same excitement and progress in its most profoundly isolated neighborhoods, in schools like J.T. Brackenridge? Can they change expectations fast enough to interrupt generations of complacency?

Martinez and Radle say they have to if they are to create a system that is, in fact, a national model for breaking down the economic segregation handicapping poor children in every big-city school district in the country.

Chapter 2: The map that changed the integration conversation

When Martinez was a toddler, his 2-year-old sister died, a tragedy that could have been prevented if his family had access to decent health care in Aguascalientes, Mexico. His father, Rodrigo, orphaned and forced to drop out of school in second grade, realized his family needed to leave if they were to do more than subsist. Rodrigo moved to Chicago and for two years saved money to bring Pedro, his mother, and his surviving siblings north. The local parish helped the family get on its feet, but Rodrigo always had to work two jobs and never earned more than $7 an hour.

In sixth grade, Pedro had a teacher who was determined to push him to live up to his potential. The tough love was effective, and Martinez entered Benito Juarez High School with 12th-grade math skills. He started high school in a class of 700. By the time Martinez graduated, there were 170 seniors left.

He had worked his way up to assistant manager at McDonald’s, but Martinez knew he could do much, much better. He took a leap of faith and enrolled in college, earning a degree in accounting at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and then an MBA at Chicago’s DePaul University.

Martinez was working in finance for the Archdiocese of Chicago when Chicago Public Schools Superintendent Arne Duncan recruited him to work for the district. After serving as its chief financial officer, in 2012, he was named deputy superintendent of Nevada’s Clark County Schools, the nation’s fifth-largest district, then superintendent in Reno, Nevada, and finally, superintendent-in-residence at the Nevada Department of Education.

WATCH – One on One with Superintendent Pedro Martinez:

When he visited Radle’s 78207 neighborhood, Martinez was struck by the same things other newcomers are: streets no wider than alleys where houses the size of garden sheds slump, rotting into the ground because there are no sewers to prevent frequent flooding.

“What I saw in my (district’s) neighborhoods were homes that hadn’t had air conditioning in decades,” he said. “And this is a community where the weather reaches 110 degrees with humidity for several months of the year.”

Then there is the street in the 78207 that Radle calls “the place where the money ran out,” a series of intersections where modern infrastructure simply quits, the sidewalks disappear, and roads sporting as much grass as asphalt narrow from two lanes to one.

Martinez thought he knew poverty, both personally and as a professional committed to eradicating it. But what he saw in San Antonio was familiar and yet shocking. The tight-knit families and their warmth reminded him of the neighborhood where he grew up. But the scope and depth of the need was stunning.

“This is the first time that I experienced a district where the entire district had such a density of poverty,” he says. “I could see very quickly because of the demographics of the children and the poverty levels, the density, that we needed to understand it in a deep way.”

Median family income in San Antonio ISD is $30,363. One in five adults aren’t high school graduates, and 42 percent don’t work. Half of the students live in single-parent households. Constant evictions mean up to 40 percent of students shuffle from one school to another.

As daunting as those realities are, the challenges facing J.T. Brackenridge are greater. Located in the poorest corner of the poorest zip code, median family income at the school is $17,000 a year. But J.T. Brack, as residents affectionately call it, enrolls students whose family income dips below $8,000 a year. As a square on the map, the school’s attendance boundary is tiny yet dense, containing three public housing projects, including Alazan-Apache Courts — one of the nation’s oldest, completed near the end of the Great Depression thanks to the parish priest’s relationship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Martinez knew that the traditional way of measuring student poverty — tallying the number of children who qualify for free or reduced-price school lunch — was wholly inadequate when it applies to virtually every student in every one of his 90 schools.

At schools near the upper range, an annual income of $45,500 or less for a family of four, students might need extra support in learning basic math and literacy skills, for example. While at schools like J.T. Brackenridge, students need backpacks full of food to take home to their families.

“Our goal is to show our staff, this is what it means to prepare our children for the next level. How do we show parents like mine, who had a second-grade education, what is possible?” —Superintendent Pedro Martinez

To draw the fine-grained portrait he needed, Martinez culled from a different set of data, the U.S. Census’s American Community Survey, which calculates median family income by city block. Cross-referenced with individual student enrollment records, that gave him a median household income level for each school. He put the information on a map, color-coded according to the census’s four corresponding income “blocks,” with Block Four the poorest.

“These are my families that make under $20,000 a year,” Martinez explains. “They are single-parent households, they don’t own a home, and most of the parents don’t have any kind of education beyond high school. In fact, we have in some neighborhoods, a very high percentage of illiterate adults.”

Education research that isn’t based on meal-subsidy data is scarce. But a working paper released shortly after Martinez created his map confirmed his hunch that the depth and nature of poverty matters in terms of a child’s educational odds.

In July 2016, professors at Syracuse University and the University of Michigan used Michigan data to determine the number of years individual students were eligible for free and reduced-price meals. At the time of the study, these students made up half of Michigan eighth-graders.

In “The Gap Within the Gap,” Katherine Michelmore and Susan Dynarski determined that students whose family income was nearest the maximum for eligibility were most likely to be “transitorily disadvantaged” — temporarily set back by a layoff or some other factor the family could bounce back from.

Meanwhile, 14 percent had been eligible their entire time in school. “Persistently disadvantaged,” their families were unable to climb out of poverty. They were more likely to go to urban schools with high concentrations of poverty than their less-impoverished peers. As a group, the poor students studied were about two grades behind their wealthier peers, but the persistently disadvantaged children were three grades behind.

Martinez knew that at some of his schools virtually all of the students carried the trauma associated with growing up in this kind of deprivation. He would have to ask both San Antonio ISD staff and the civic and philanthropic groups eager to contribute to commit to providing the extra support necessary to address this intergenerational trauma.

Martinez carried his map around to Rotary Club breakfasts, meetings with teachers, and any other gathering where it might spark discussion. When he took it to other parts of San Antonio, he pointed out that their poverty bore little resemblance to that of his district. When he showed it within the district, he flagged the outliers.

J.T. Brackenridge was one of them, very near the bottom in terms of poverty but not academic performance. In fact, the school had a higher percentage of students scoring “advanced” on annual state reading and math assessments than the lone district school with median family income anywhere near the national average, about $54,000.

Martinez and Radle had some hypotheses about this. For starters, the close relationships in the 78207 can keep things like evictions and job losses from being as catastrophic as they might be. Though it has since experienced some turnover, the school had an unusually stable staff, Radle notes, and with periodic exceptions, the neighborhood experienced much lower crime rates than might be expected.

Usually when Martinez highlighted the surprises on his map — J.T. Brack’s scores were decent, but the district’s Young Women’s Leadership Academy was one of the best schools in the country in terms of academic achievement among low-income children — people would ask why. What went right, and could they build on it? And if kids were learning in the elementary years, how come college enrollment and graduation were still so elusive?

Conventional wisdom is that multi-generational poverty is the cause of low academic achievement. It’s undoubtedly true that decades of inequities in places like San Antonio’s urban core have created devilishly tough circumstances. But as people who also see the richness in the 78207 and similar communities, Martinez and Radle agreed that beliefs about poverty — the pobrecito problem — are also a very real barrier.

Martinez understood that to parents with little experience beyond their isolated neighborhood, the payoffs from a quality education aren’t tangible. If you don’t know anyone who has a college degree or a comfortable salary, you literally can’t envision how to get those things.

“Our goal is to show our staff, this is what it means to prepare our children for the next level,” he says. “How do we show parents like mine, who had a second-grade education, what is possible?

“I came to the conclusion very quickly that if I didn’t change that conversation that we were going to have this cloud of low expectations and it was going to continue,” Martinez adds. “Our first goal was to redefine excellence.”

Beth Hawkins Explains — ‘In 20 years of writing about failed integration efforts, I’ve never seen anything like this’:

Chapter 3: Integrating by income — when 93% are in poverty

A few months after he arrived in San Antonio, Martinez approached the principal of the most academically successful school in the metro area, the International School of the Americas. Would Kathy Bieser leave her prosperous north-metro school district to design and lead a school in San Antonio ISD?

And not just any school. Martinez wanted to create a gifted and talented academy that would be open to any child in the district, regardless of test scores or zip code. The plan had multiple layers.

There’s a trove of evidence that one way to increase student achievement is to offer more challenging academic material. Requiring students to think critically about knowledge gleaned across different subject areas, the approach used in gifted and talented programs, is precisely the kind of “higher order” learning now shown to be invaluable in raising academic achievement. But when it is offered at all, it’s typically reserved for children who already are ahead. Screened infrequently, children of color are rare in gifted and talented programs.

With 93 percent of his district’s students impoverished, the only way Martinez could create socioeconomic diversity in schools was to attract families from more affluent communities. Convinced a gifted and talented program would be an immediate draw, Martinez would reserve 25 percent of seats for students from other districts.

Dissatisfied with offerings in even the most prosperous traditional districts, San Antonio families of means were decamping for private schools or for one of the nation’s most rapidly growing charter school sectors. Several of the charter networks expanding in the city, such as IDEA and KIPP, have reputations for being academically challenging.

Bieser was well positioned to set a high bar, certainly, but Martinez had another reason for tapping her. The school where Bieser was principal had been conceived of as a teacher-training lab for nearby Trinity University, whose school of education is one of the best in the nation. Hard-pressed to compete financially for teachers, Martinez needed a “grow-your-own” talent pipeline.

The newly created Advanced Learning Academy would have a partnership with the college, which would place 10 educators-in-residence and four would-be principals in the school each year. Instead of a few weeks of student teaching at the end of their educations, the teacher-in-training would spend an entire year working side-by-side with master teachers.

Because the pairs continually talk through the choices they are making in the classroom, in Bieser’s experience, residencies are beneficial not just to the student teachers, but to their veteran mentors, too.

“The magic involves being present at the very beginning of the school year almost to the very end of the school year,” she says, “seeing the flow of the year and having a classroom as well as a school that’s deeply reflective. And so not only the resident, but that master teacher, that mentor teacher are all the time kind of talking out loud about their craft.”

San Antonio ISD would pick up a large portion of the cost of training if the new teachers agreed to stay in the district for several years. Significantly, when they completed their residencies, they would take the high expectations of the gifted and talented model with them to other district schools where few believed impoverished students would benefit from academic rigor.

Advance Learning Academy had a waiting list even before the first day of school in August 2016. Encouraged, Martinez rolled out the welcome mat, offering to reopen schools mothballed because of declining enrollment for teachers and principals interested in creating new schools with dynamic models.

Watch — On Scene at San Antonio’s Advanced Learning Academy:

He had no shortage of takers. When the 2017-18 school year started, San Antonio ISD boasted a dual language program, a Montessori school, high-tech and early-college high schools, a teacher-residency school run by the Relay Graduate School of Education, and a number of specialized programs within existing schools. This year, a third dual language school came online, along with an all-boys school and a host of other new programs.

“We’re seeing again such a great response from our families. We have 10,000 applications right now for 3,000 choice seats in our district. We’ve never seen that in the history of the district,” Martinez says. “What I’m very hopeful for is that I’m seeing a community movement. I’m seeing conversations change.”

But with success came a new challenge. As applications rolled in for seats in Advanced Learning Academy’s second year, they followed a trend common throughout the country: As soon as a new school acquires a buzz on the parent grapevine, middle- and upper-class families can quickly dominate.

“We love the fact that our schools are becoming popular, but could we create our own problems?” Martinez asks. “Could we further segregate our own families just based on our success?”

Martinez needed to make sure families from Block Four, the poorest of the poor, got their share of seats in the new schools. He recruited a former teacher who was trying to create “diverse by design” schools in Dallas, Mohammed Choudhury, to start and lead an Office of Innovation.

Choudhury, whose Twitter bio lists desegregation as a job duty, immediately began creating an enrollment system that would reserve seats not just for out-of-district families and neighborhood residents, but for children from each of the income “blocks” on Martinez’s map. And he dug even deeper into the data to incorporate information about parents’ educational attainment, home ownership, single-parent status, and other factors.

Without careful controls, Choudhury says, school choice can create “islands of affluence.” So for the 2018-19 school year, one-fourth of the 3,000 open seats in the 31 choice and magnet schools were reserved for students with the highest needs.

And he and Martinez are working to locate new innovative schools in neighborhoods where geographic and economic isolation make school choice an abstraction.

Chapter 4: Living in two worlds

One day last spring, as she was driving past J.T. Brackenridge, Radle spotted a former student of hers, Priscilla Lucio, on the way home from picking up her son, Carlos Zuniga Jr., from school.

“You don’t have, like, beans on the stove or anything like that do you?” Radle asked, making sure they had time to talk.

“No,” Lucio replied. “I did but I took them off.”

The boy, better known as C.J., had just been accepted into a new engineering program at Lanier High School, Lucio told Radle. They had gone to visit and C.J. had become captivated with the idea of working on jet engines. He’s never been on a plane, but if he had the chance, he said, he’d fly to Tokyo.

Lucio had dreamed of being a pediatrician but dropped out in 11th grade when she became pregnant with C.J. The visit to Lanier’s high-tech program changed what she wanted for her first-born.

“At first, growing up and having him, I would say, ‘Oh, I want him to join the (armed) services,’” she said. “But now, I think there’s more out there in life than just that … I would love for him to go to college.”

How would C.J. feel about leaving? How would his family? At this, the talk became more tentative. “It would be hard for my mom to let me go to college just for the fact that I’m the oldest and I’m the first one to go,” C.J. says, looking at his feet and not at his mother.

Named one of the 25 most influential Latinos in the United States by Time magazine, Lionel Sosa is a celebrated native son of the 78207. He has advised presidents and the heads of Fortune 500 companies, and yet he is intimately familiar with the shift of perspective Lucio and her children are undertaking. At 79, he has 50 grandchildren and great-grandchildren, many of whom live in the neighborhood.

Sosa’s own kids are from two marriages, the first to a woman who did not finish high school and the second to a college graduate he married after he made a fortune in advertising. His first four children didn’t graduate from high school. The next two graduated from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and Yale University.

“I live in these two worlds,” he says. “A world where there was no education, and life has been tough, and a world with education, that’s not quite as tough.”