by Duncan Wood

Mexico’s identity as a North American nation has crystallized in the years since NAFTA was signed. Despite questions about its incoming president and major pressure points with Washington, that identity will not erode.

When I first moved from Toronto to Mexico City in January of 1996 to pursue a career as a young professor, I entered an entirely new world. Having grown accustomed to the order, stability, and relative prosperity of Canada, Mexico seemed chaotic, volatile, and impoverished. Although I soon experienced the diversity of Mexican society and came to understand the country’s huge economic potential, I remained mired in a narrow-minded view that was based on the contrast with Canada, a country that had been my adopted home for the previous six years.

This, perhaps understandably, led me to be naively critical of Mexico. I would complain about the failings of Mexican bureaucracy, of the economy, of social norms, and of the rule of law. However, a distinguished colleague of mine at the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México, Professor Jesús Velasco Márquez, soon called me to task. He impressed upon me, in kind but stern terms, that the real question was not “Why isn’t Mexico more like Canada or the United States?” but rather, “Why isn’t Mexico more like Guatemala?” This juxtaposition of two alternate realities, one North American and the other clearly Latin/Mesoamerican, made me stop in my tracks. It made me consider not just how much remains to be done in Mexico, but how far Mexico has come and how successful the country has been.

I soon came to see Mexico as unique in the hemisphere – a country that refuses to fit neatly into preconceptions of North versus Latin America. It is a country that has made an extraordinary transition over the past 25 years, advancing in its economic development, its democratic practice, and its place in the global system. And yet, it continues to suffer from the imperfect implementation of the rule of law, grinding poverty, and weak institutions. Mexico is so close in developmental terms, and yet still so far away. Over the next two decades, I became convinced that Mexico is on the right path. At the same time, I recognized that in the Mexican context, progress would definitely not be linear, that it proceeds in fits and starts, and that the country’s embrace of a revolutionary identity is really far more evolutionary in reality

Then, in July 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO, won the Mexican election in stunning fashion. Along with a landslide victory in the presidential poll, his Morena party now also dominates Congress and state legislatures. AMLO has argued that Mexico has passed through three major transformations in its history: its independence movement, the reform period of the 1850s and 1860s, and the Mexican Revolution of the early 20th century. Now, he promises a “fourth transformation” of Mexico, one that will propel the country towards a more just, prosperous, and corruption-free future, with the result as revolutionary as the first three.

But it would be a mistake to assume that this new direction will divert Mexico from its path of convergence with North America. Mexico has become so deeply embedded into the region, and has become so dependent on trade, investment and joint production with the United States and Canada, that such a departure would cause severe economic and political disruption – and an existential crisis. That holds true even with the ongoing tensions of the Trump era in bilateral affairs. AMLO appears committed to a North American destiny, and, in fact, he may even be better equipped to deal with President Trump than his predecessor was.

A Continental Identity

In the early 1980s, Mexico faced a moment of reckoning. The confluence of a deep Latin American debt crisis; the return of Mexican technocrats educated in U.S. neoliberal economic practices; pressure from the World Bank and IMF; and the demands of international investors pushed the country to embrace market principles and open its economy to the world. By 1994, Mexico had joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and, most importantly, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Fundamentally deeper ties with the United States and Canada, in particular, were being forged.

These changes, in turn, led to a change in the very identity of Mexico as a country and as a people. From being a closed and inward-looking nation, Mexico and Mexicans gradually, slowly began to explore new horizons. The country saw a flood of imported goods hitting supermarkets and the arrival of new products from around the world, seen most obviously in the availability of new car brands and models. Textbooks were rewritten to include foreign affairs and there was an explosion of interest in international relations programs at universities. By the early 2000s, Mexico had become a globalized economy, relying on foreign direct investment, engaging enthusiastically in multilateral forums, and exporting more manufactured goods to the world than the rest of Latin America combined.

Because of increased commercial and social intercourse, and as millions of Mexican migrants made new lives up north, the United States ceased to be viewed as the country that had stolen half of Mexico’s territory.

Mexican foreign policy itself began to change. Adherence to the long-standing Estrada and Carranza doctrines – which warned against interference in the internal affairs of other countries (thereby protecting Mexico from such outside interference) – gradually weakened. The country became a more vocal critic, especially within Latin America. When Foreign Secretary Jorge Castañeda began to openly criticize the Cuban government of Fidel Castro in 2002, it marked a sharp and controversial break with Mexican diplomatic tradition. New civil society organizations and think tanks were founded to reflect these changes, raising new awareness and understanding of international affairs.

Central to this broadly-based internationalization was the concept of Mexico as a North American nation. Because of increased commercial and social intercourse, and as millions of Mexican migrants made new lives up north, the United States ceased to be viewed as the country that had stolen half of Mexico’s territory. Mexico was moving past its traditionally contentious, confrontational, and controversial relationship with the U.S., which became increasingly viewed as a partner, in the region and the world. This change, of course, did not happen overnight and was far from linear; Mexicans continue to harbor suspicions of the U.S. government, and public opinion depends heavily on the current phase of relations and the current occupant of the White House.

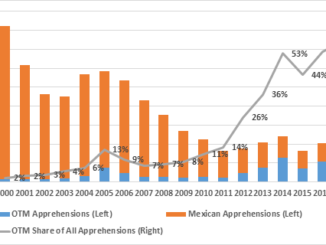

Especially since the signing of NAFTA – which holds the status of a legally binding treaty in Mexico, unlike in the U.S., where it is an agreement – the Mexican government has defined its place in the world firmly as a member of the North American region. Today, the country has deeper trade, investment, manufacturing, and energy ties to its continental neighbors than to the rest of the world – at the center of which is an overwhelming dependence on bilateral trade with the United States, which receives about 80 percent of Mexican exports.

Canada was embraced first as a necessary extension of the relationship with the U.S., and then as a strategic partner in its own right. (Notably, during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Canada and Mexico found themselves joined as close allies of the U.S. and heavily dependent on good economic relations with their neighbor, but unable to join the “coalition of the willing.” Throughout the trying period, Mexico and Canada emphasized the importance of their bilateral relationship in ways that had hitherto been unexpressed). Economic ties have quadrupled since 1994, and Mexico is now Canada’s third most important trading partner. The inseparability of North American manufacturing systems (seen in a wide range of sectors, but none more clearly than the automotive industry), have made “North Americanness” an undeniable fact for Mexicans. While Mexicans continue to see themselves as Latin Americans in a cultural sense, in economic and political terms the transformation has been clear.

During the administrations of Presidents Vicente Fox Quesada, Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, and Enrique Peña Nieto, this continental identity became something of a diplomatic mantra, with regular meetings of the North American Leaders Summit (NALS), a series of regional initiatives on security and economic competitiveness, and even the recent three-country bid for the World Cup. The NALS, in fact, has been perhaps the most impressive manifestation of the North American partnership. Taking place on eight occasions since 2005, the leaders of the three countries have engaged in a process of socialization that has brought their bureaucracies and policies into closer alignment. What’s more, it has focused the attention of all three administrations on the region. After the 2016 summit, the governments agreed to put in place a trilateral coordination process to ensure that NALS commitments were fulfilled. That vision has been stymied by tensions arising from President Trump’s attacks.

A Book and Two Letters

However, notwithstanding the preceding decades of growing North American identity, political developments in Mexico over the past year have raised doubts about the sustainability of this convergence. While Mexico’s president-elect has shown little interest in foreign relations during his lengthy political career, his rise in popularity in 2017 and 2018 generated concern that he would distance the country from the U.S., and would instead focus on outreach to Latin American countries for common cause.

Some analysts have pointed to AMLO’s criticism of NAFTA in previous campaigns for the presidency, when he attacked the agreement for benefitting the United States and Canada more than Mexico. During the 2018 election campaign, of course, he had to contend with repeated verbal attacks by President Trump on Mexico and its people. In response, AMLO published a book titled “Listen Up, Trump!” in which he seized on bilateral tensions as a way to define his own plan for Mexico. He also fervently opposed Mexico’s landmark 2013 energy reform, seeing it as a betrayal of sovereign control over the nation’s hydrocarbon resources. As U.S. firms have won a number of major contracts thanks to the reform, some have seen his opposition as a challenge to ongoing good relations.

Fears of a break from the country’s northern neighbors (its bordering neighbor in particular) have so far proven unfounded.

What’s more, the president-elect’s left-wing political bent has drawn comparisons to Latin American socialist figures such as Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, each of whom adopted a more-or-less antagonistic approach to the United States during their presidencies. Additionally, AMLO’s Morena is an “umbrella party,” one that incorporates members from across the political spectrum, and some of the more radically anti-American voices in Mexico have previously been heard from within its ranks.

However, these fears of a break from the country’s northern neighbors (its bordering neighbor in particular) have so far proven unfounded. It appears that AMLO does not intend to pivot his country away from its continent-facing orientation. Part of that calculus, he seems to realize, is making nice with the controversial U.S. president. During the election campaign, AMLO generally resisted the provocations from Washington, as he repeatedly emphasized the importance of bilateral ties – and the importance of avoiding a rupture between the two nations. On NAFTA, he reversed his previous skepticism and criticism, arguing that the agreement had generally been good for Mexico, while recognizing that it needs an update. And AMLO was the only candidate to give a public speech in Washington during the presidential campaign.

President-elect López Obrador’s letter to President Trump…

Thus far, the relationship between the president-elect and Trump gives the appearance of being dramatically friendlier than that between Trump and Peña Nieto. It has also emerged that the U.S. president has nicknamed AMLO “Juan Trump,” reflecting the fact that he sees some of himself in his soon-to-be counterpart’s character and behavior. AMLO has already met with Secretary of State Pompeo, Secretary of Homeland Security Nielsen, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin, and Senior Adviser Kushner, the latter meeting notable for its congratulatory and exceedingly friendly tone. For his part, a number of AMLO’s decisions appear to have been made with U.S. relations in mind; his choice for foreign minister, Marcelo Ebrard, has been interpreted as an olive branch to Washington.

Perhaps most dramatically, AMLO has released the wording of a letter he wrote to President Trump immediately following their half-hour phone conversation on July 2. In that missive, AMLO lays out much of his plans for government, while emphasizing key points of concern for the United States, including economic development, trade, migration, and security. In a strikingly personal tone, the letter ends on a note of empathy, comparing the two men’s career struggles and their respective commitments to serving voters and displacing the “establishment” (the English word is used in the otherwise Spanish-language message). The letter is a remarkable statement of purpose, and one intended to reassure the northern neighbor at the same time as it opens the door to further dialogue.

… and President Trump’s letter in response.

In turn, President Trump’s letter in response was also released. The exchange, in today’s electronic age, especially with a U.S. president who has used Twitter as his preferred medium for diplomacy, is a remarkable thing. In Mexico, it is often said that the “forms” matter as much as the message, and in this case, the two leaders have resurrected a more “formal form.” It allowed AMLO to lay out his message uninterrupted, and committed Trump to a long-form, written response. In the short term, at least, this is a diplomatic success for Mexico’s president-elect.

Asymmetry and Balance

Importantly, AMLO and his team have signaled that they are looking for a rapid conclusion to NAFTA negotiations, hoping to make significant progress during the summer of 2018, before he actually assumes the presidency. Although this positive outlook on NAFTA is difficult to support with evidence, there does at least appear to be a new air of optimism on both sides of the border. Moreover, as the negotiations advanced at the end of July, AMLO’s team reaffirmed their commitment to a trilateral deal, refusing to exclude Canada in favor of a bilateral agreement. (Shortly after Secretary Pompeo’s visit on July 13, AMLO received a delegation led by Canadian Foreign Minister Freeland. Again, the meeting was extraordinarily friendly, with Canada keen to impress upon the president-elect that a trilateral approach in NAFTA is essential). The Mexican president-elect has bought into the North American idea, and knows that the success of his presidency depends on NAFTA’s survival. Mexico should to aim to “diversify our trade relations,” AMLO recently said, but “without neglecting the importance of the economies of the United States and Canada.”

Of course, there remains much about which to be concerned in the relationship with the U.S., which obviously constitutes much of Mexico’s North American anchor. Beyond the huge issues on the agenda – and we must recognize that agreement on key points of contention, such as NAFTA, the border wall, and migration remain as elusive as ever – there is only so much that Mexico’s president-elect can do to set the tone. He should expect that Trump will continue to berate Mexico, especially over issues that are popular themes with his supporters. Mexico is now, and will remain, as much an issue of domestic politics in the U.S. as it is one of foreign policy. Political expediency, therefore, will guide interactions as much as national interest.

I have come to see myself as a “North American citizen.” What’s more, I have also come to view the three NAFTA countries as sharing a similar destiny.

But despite the tensions, despite the temptation to fight back against taunts, despite the political incentive to fight fire with fire, tweet with tweet, AMLO has opted for a cautious, formal, and balanced diplomatic approach to Trump. This reflects the deep dependence shared by the two nations, one that is certainly asymmetrical, but definitely mutual. The United States may currently be a cause of anxiety for Mexico, and will often be a diplomatic foil; but each country will always be the other’s essential partner and inescapable neighbor. Canada, too, is essential to Mexico’s equation, including to balance the overwhelming power of the United States.

It is now 22 years since I moved from Toronto to Mexico City. I now live in Washington, but visit Canada and Mexico every few weeks. In crisscrossing the continent over the years, I have come to see myself as a “North American citizen.” What’s more, I have also come to view the three NAFTA countries as sharing a similar destiny. Over the past two decades, Mexico, in particular, has tied itself irrevocably to the region, and the region is stronger for it. The new government there seems to have recognized that, in addition to being inescapable neighbors, the three North American nations need each other and will continue to share common cause, far beyond the terms of their current leaders.

Duncan Wood (@AztecDuncan) is the director of the Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute. The former head of the Department of International Studies at the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México, he has lectured and published widely in the United States, Mexico, and Canada on intracontinental issues.