by Shannon O’Neil

On the eve of Mexico’s election, even before the National Electoral Institute called the results, President Donald Trump tweeted congratulations to the presumptive victor Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. The two leaders followed up the next day with a congenial phone call. The following week three U.S. cabinet secretaries, along with senior White House adviser Jared Kushner, headed to Mexico City to meet their counterparts and the president-elect.

The press and markets have taken these gestures as signs of more positive relations ahead. Don’t be too sure. These initial niceties paper over deep chasms in priorities, positions, and domestic politics. A blow-up may not be far away.

Lopez Obrador’s recent letter to Trump shows how different his take is on what a promising bilateral relationship entails. The seven-page missive lays out his economic development plans for Mexico, in minute detail, and reflects his view that the solutions to bilateral challenges of migration, security, and commerce depend on Mexico’s economic advancement.

It is safe to say President Trump has little interest in ambitious plans to plant 1 million hectares of trees in Mexico’s most poverty-ridden states, much less any inclination to help finance this venture. The same goes for Lopez Obrador’s infrastructure goals: refineries in Tabasco and Campeche, a bullet train from Cancun to Palenque, or a rail corridor connecting the Pacific to the Atlantic across the southern Isthmus of Tehuantepec in a bid to rival the Panama Canal. This U.S. administration isn’t big on partnering on economic development. Look for Lopez Obrador to be turned down or ignored on the economic issues that matter most to him.

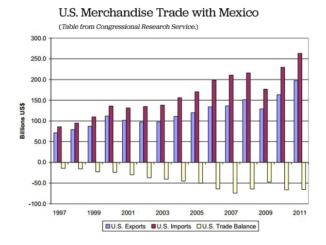

Likewise, he is unlikely to be the NAFTA partner Trump is looking for. The incoming president supports keeping the 25-year-old free trade agreement, recognizing the benefits for investment. His designated trade lead, Jesus Seade, is working with the current Mexican negotiating team to prepare to pick up the mantle, joining them in Washington talks. Despite Trump’s demand and veiled threats to quickly reach an agreement, Lopez Obrador and his team aren’t deviating from Mexico’s current redlines — including the sunset clause, dispute settlement mechanisms, and auto content rules — or showing any interest in bilateral talks, something Trump has also been encouraging.

There is also little common ground on Central American migration. Led by Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen and Customs and Border Protection Commissioner Kevin McAleenan, the U.S. has pushed for a safe third-country agreement, which would force Central Americans passing through Mexico to apply there for asylum.

While this would largely solve the U.S. problem — border agents could turn back every man, woman, and child seeking refuge — there is less than nothing in it for Mexico. The new government would struggle to process tens if not hundreds of thousands of refugee applications and to build the infrastructure and camps required to house desperate Central Americans — a crisis potentially overwhelming Lopez Obrador’s young presidency. And the Trump administration looks unwilling to provide the billions of dollars Europe has used to gain Turkey’s acquiescence to a similar deal. Instead, it is still fighting Congress for billions for a border wall.

The two leaders are equally at odds about how to lessen these migration flows over time. Lopez Obrador calls for a comprehensive regional economic development plan to attack the root causes of migration. Trump has proposed cutting such aid to Central America by nearly $200 million, or 30 percent each of the last two years.

Security cooperation, too, looks to be interrupted. Every change in administration brings something of a pause. Yet this halt will be prolonged by Mexico’s plans to create a new Public Security Secretariat, National Guard, and intelligence agency; setting up these new bureaucracies will delay the start of a yet to be defined domestic security strategy.

And even once it is up and running, it won’t be headed in the same direction as the U.S. Lopez Obrador’s ministerial appointees are talking about legalizing marijuana, providing amnesty for illicit crop farmers and expanding scholarships as ways to reduce violence. This doesn’t jibe with the Trump administration’s hard-line approach to regional security.

Diplomatically, cooperation on an imploding Venezuela (let alone Nicaragua or Cuba) is also about to fade, as Mexico’s new leadership reverts to a more traditional hands-off international approach. Washington won’t be pleased.

Of course, few traditional allies have remained in the U.S. president’s good graces. Just ask Canada’s Justin Trudeau, Germany’s Angela Merkel, Japan’s Shinzo Abe and France’s Emmanuel Macron. As the 2020 elections approach, Trump will be tempted once again to demonize Mexico. With his own base to feed, Lopez Obrador will be hard pressed not to respond in kind.

Lopez Obrador closes his letter to Trump by talking about how they both overthrew the “establishment” in their rise to office. What he misses is that this establishment actually cared about NAFTA, the Dreamers, and Mexico more broadly.

True, the deepening partnership of the last 25 years has been more an anomaly than a norm. Yet even during past disagreements, despite mutual suspicions and distrust, the two nations found ways to work together. If a standoff between presidents leads back to a more institutional relationship, away from the personalization of the last year and a half between Jared Kushner and outgoing foreign minister Luis Videgaray, that, too, may set the relationship on a steadier path. Just don’t expect it to be better.

Shannon K. O’Neil is the vice president, deputy director of studies, and Nelson and David Rockefeller senior fellow for Latin America Studies. She is an expert on Latin America, U.S.-Mexico relations, global trade, corruption, democracy, and immigration. follow @shannonkoneil