by Laura Collins and Anne Wicks

This month, the White House unveiled the National Council for the American Worker, a new initiative focused on training and retraining American workers to fill the in-demand jobs of today. As part of this initiative, the administration is asking companies to sign the Pledge to America’s Workers to commit to invest in workforce development.

Reskilling American workers is vitally important to the continued productivity of our labor force. With a growing economy and tightening labor market, American businesses desperately need workers with the necessary skills. As the White House rightly notes, there are millions of job openings but few workers with the skills necessary to fill them.

Investment in worker retraining can help companies fill their job openings. But it is not the only good policy solution to this situation, and it is certainly not the quickest way to ensure companies get the labor they need to continue growing our economy.

The U.S. needs to address its workforce pipeline on three fronts: immigration and temporary workers, retraining and lifelong learning for current workers, and an education system that prepares our future workers for the economy of tomorrow. American businesses need skilled workers now; retraining our workforce cannot meet our current labor demand. Only a robust, market-based immigration system can meet employer needs.

Unfortunately, this administration has pursued policies that knee cap the current legal immigration system, artificially restricting the pool of available labor and unnecessarily slowing the economic success we have experienced to date. Many of these actions are not directly targeted to employment-based green cards and temporary visas, but they have had a chilling effect nonetheless.

Stepped up vetting of H-1B highly skilled visa applicants, the travel ban, reduced refugee admissions, ending temporary protected status for several countries, and the proposed rescission of the employment program for the spouses of H-1B visa holders are all actions this administration has taken that have undercut the legal immigration system, prevented firms from accessing a capable pool of workers, and hindered economic growth.

This administration has increased the number H-2B visas available for low skilled non-agricultural temporary workers. While this increase is positive and was much-needed in many summer seasonal industries, it does not fully address the labor force gaps in these industries, nor can these workers fill the millions of other middle skill job openings.

An increase of a few thousand temporary workers is simply not enough to meet current labor demands across the U.S. We need to increase current immigration levels to meet the needs of our 21st century economy in the short term.

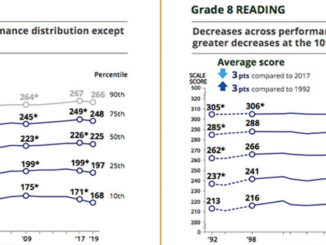

In the long term, we need to strengthen the education to workforce pipeline by ensuring that all students, regardless of their background, have access to high quality education. The most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores showed that American student growth in reading and math continues a decade-long stall. The 4th and 8th graders included in the 2017 scores will soon be the workers our business community seeks, and they are struggling.

While we cannot predict exactly what the jobs of the future will be, we can reasonably predict that workers will need to read, to write, to solve problems, and work effectively with others. Preparing young people for meaningful wage careers does not mean giving them access to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) or iPads—although those are not necessarily bad things. It means that we first must make sure students are on track in reading and math.

The business community was a meaningful partner in the education reform movement in the 2000s when education accountability policies were strong and NAEP scores were ascending, particularly for our most vulnerable children. Their role still matters – and workforce development is often where the results of education policy often become tangible.

The administration should be commended for its efforts to strengthen our workforce and retrain workers that have been left behind by technological change. But it is not enough to simply commit to improving their skills. A strong labor force starts with an excellent education system and is supplemented by welcoming workers from around the world to labor on behalf of our economy. We hope the business community signs on for all three.

Laura Collins is deputy director of the economic growth initiative of the George W. Bush Institute and Southern Methodist University. Anne Wicks is director of education reform at the George W. Bush Institute.