by James C. Capretta

The trustees for the Social Security and Medicare trust funds released their annual reports last week. And the takeaway? Despite a strong economy, both programs have large and growing financial deficits. Unfortunately, the gap between spending and revenue for these programs is likely even larger than the official projections show because of assumed but unrealistic cuts in medical care payment rates and the persistently low birth rates of recent years.

The Social Security report estimates the program will run out of reserves in 2034, after which benefits would have to be reduced by about 25 percent to keep spending within available annual revenue. Over 75 years, Social Security has an unfunded liability of $13.2 trillion. Restoring permanent solvency to the program would require raising the payroll tax rate immediately from today’s combined employer-employee rate of 12.4 percent of taxable payroll to 15.2 percent. Alternatively, Social Security benefits would need to be cut on a permanent basis by about 17 percent.

The financial hole for Medicare is even deeper. The Medicare hospital insurance trust fund will run out of reserves in 2026. Last year, the trustees expected the program’s reserves to last until 2029. Medicare has a second trust fund, for physician and outpatient services and for prescription drugs, that is permanently “solvent” because it has an unlimited tap on the general fund of the Treasury. What this really means is that premiums paid by the beneficiaries will cover only about 25 percent of program costs; the rest of the spending is unfinanced. Income and corporate taxes fall far short of what is needed to cover these costs along with the rest of the government’s obligations. Medicare’s overall unfunded liability over 75 years is more than $37 trillion.

Taken together, the combined unfunded liabilities of Social Security and Medicare are more than $50 trillion, according to official government projections. Unsettling as these estimates are, they are probably optimistic — for two reasons.

First, the Medicare projections assume deep, permanent, and on-going cuts in payment rates for physicians and hospitals that are difficult to believe will be implemented.

In 2015, Congress passed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), which revamped how physicians are paid by Medicare. The law scrapped the despised Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) budgeting mechanism and put in its place stringent restraints on annual payment increases. In 2018, physicians got a boost in payments of 0.5 percent, and will get one next year of 0.25 percent. For 2020 through 2025, current law provides for no inflation increase at all for physician fees paid by Medicare. Beginning in 2026, physicians who participate in what are called “alternative payment models” can get annual fee increases of 0.75 percent, while those who don’t will get increases of 0.25 percent each year. These payment increases would be well below the expected medical inflation rate of 2.2 percent, which means physicians would get a real cut in payment rates from Medicare each and every year. Over time, Medicare’s payments for physician services would plummet compared to what private insurers have to pay for the same services.

Similarly, in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Congress imposed deep cuts on payments for inpatient hospital services and other forms of institutional care through a “productivity adjustment factor.” The productivity adjustment factor is a measure of economy-wide improvement in output per worker. The authors of the ACA assumed hospitals and other facilities could match this level of productivity improvement each year, and so they reduced the annual inflation increases paid to these facilities by the assumed productivity increase. As an example, if inflation and hospital costs rise 3 percent and productivity goes up 1 percent, then hospitals get a 2 percent inflation bump instead of a 3 percent increase. The ACA imposed this cut starting in 2011, and it is to occur every year into the future. The compounding effect of the annual cuts means this is one of the largest payment rate reductions in the program’s history.

The actuaries responsible for the financial projections of the Medicare program continue to warn that it is unrealistic to assume these cuts can be implemented every year into the future. Among other things, they project that the physician cuts would push Medicare’s fees from about 75 percent of private insurance payments today to less than 60 percent in 2030. Medicare’s payments to hospitals would fall from just above 60 percent today to below that threshold in 2030, and to around 50 percent in 2050. The actuaries warn that these low payment rates could lead to facility closures and harm access to care for the elderly.

More realistic assumptions would add trillions of dollars to Medicare’s unfunded liabilities. The actuaries estimate that if, first, the productivity adjustments for hospitals were set at 0.4 percent (instead of the higher level found in the wider economy), and, second, the annual payment increases for physicians were based on actual measured input costs, then Medicare’s overall spending would be 11 percent higher in 2050 than what is forecast in the trustees’ report.

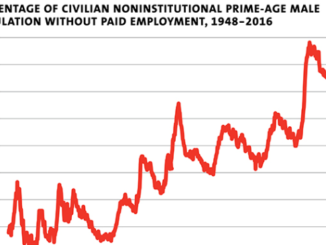

The second reason that both the Social Security and Medicare projections may be optimistic is the recent news of declining birth rates. Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released data showing that the birth rate in the U.S. is now at its lowest level in 40 years. In 2017, the total fertility rate (measured as total births per 1000 women of child-bearing age) was 1.76, down from 2.07 in 2008 and far below the population replacement level of 2.1.

The birth rate fell in the aftermath of the deep recession of 2008 to 2009, which was expected. But it has not yet started to rise again to pre-recession levels. This is worrisome because pay-as-you-go systems like Social Security and Medicare depend heavily on future growth in the labor force to remain solvent. If the birth rate remains at the current level indefinitely, the problems for these retirement programs will be much worse than the 2018 reports indicate. The Social Security projections assume a long-term total fertility rate of 2.0. If, instead, the rate is 1.8, the financial hole for the program will be about 25 percent deeper than is projected in the 2018 report. The deficit for Medicare’s hospital insurance trust fund will also get much worse with fewer births, as fewer taxpayers will be paying into the program in future years.

As the bad news on entitlement spending and the fiscal outlook rolls in, the silence among the nation’s political leaders is deafening. But they can’t say they haven’t been warned. The trustees’ reports have been sounding the alarm for years. When the crisis hits — as eventually it will — political leaders will have no one to blame but themselves for not acting when they had the chance to do so.

James C. Capretta is a resident fellow and holds the Milton Friedman Chair at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where he studies health care, entitlement, and US budgetary policy, as well as global trends in aging, health, and retirement programs.