by Tim Henderson

Hispanic immigrants here remember June 9, 2011, the day House Bill 56 became law.

“People got scared,” said Noel Mendoza, who came here from Mexico about 17 years ago. “They thought they were going to get rounded up and put in jail.” Friends in the tightknit community disappeared overnight, leaving homes full of furniture and cars in driveways, Mendoza and other residents said.

The law, intended to “stem and reverse the flow of illegal aliens into Alabama,” made it a crime to be an undocumented immigrant, or to transport, hire, or rent housing to one. Experts and community leaders say it’s the main reason there are fewer Hispanics here than there used to be.

In most places in the South, the Hispanic population has been growing in recent years. But there are a few spots in the region where the Latino population has been shrinking.

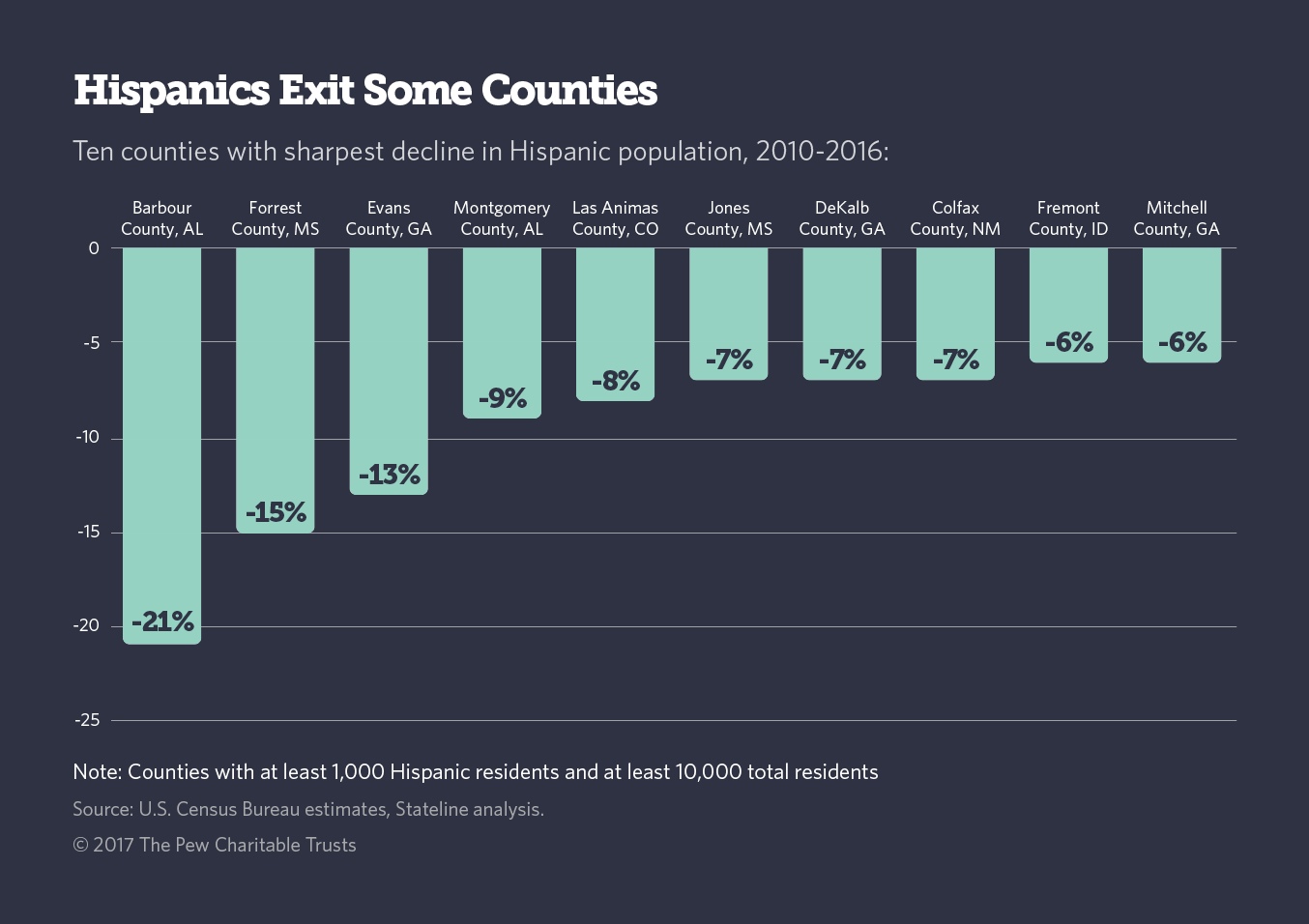

The biggest drop came here in Barbour County, about 80 miles southeast of Montgomery, where 21 percent of the 1,387 Hispanic residents in 2010 were gone by 2016, according to a Stateline analysis of U.S. Census estimates.

In all, 34 large U.S. counties have seen their Hispanic populations decrease since 2010, and 20 of them are in the South, including five each in Alabama and Georgia and three in Mississippi. Almost half of the 330 counties where the Hispanic population grew by 25 percent or more also are in the South.

Outside the South, New Mexico and Colorado dominate the list of counties where the Hispanic population declined. Those were traditionally Hispanic counties in northern New Mexico and eastern Colorado, according to a Pew Research Center study, and people are leaving in search of more economic opportunity. (The Pew Charitable Trusts funds the Pew Research Center and Stateline.)

The reasons for the scattered losses in the South may be similar to the perfect storm that hit Barbour County in 2011: a tough immigration law, including a provision requiring employers to screen workers’ legal status using the federal E-Verify program, and a Hispanic community that included many undocumented immigrants who were not well organized or able to defend themselves.

Laws aimed at illegal immigrants were enacted around the same time in Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina.

“Alabama’s was the most far-reaching, and as a result many people just disappeared,” said Naomi Tsu, who has worked on legal challenges to state immigration laws in Southern states for the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).

A federal court struck down much of Alabama’s law in 2012, including requirements that schools check the immigration status of students and parents, and bans on rentals to undocumented immigrants. The court also threw out a provision that made illegal immigration a state crime, punishable by 30 days in jail and a $100 fine, and gave state and local police the power to request a green card from anybody as proof of legal status.

Many of the other counties where the Hispanic population declined share similar characteristics with Barbour County, Tsu said, including largely undocumented immigrant populations and employers such as poultry processing plants and sawmills that require hard work for relatively low wages.

“The businesses that hire most of the people started asking for papers and they couldn’t produce them,” Mendoza said. “They went back to Mexico or sometimes California or New York, where they help Hispanics.”

Some Urban Areas Boom

In most cities in the South, the Hispanic population has been increasing. But some urban areas have also seen decreases.

Near Atlanta, DeKalb County’s Hispanic population dropped 7 percent. Ted Terry, the mayor of Clarkston, said refugees with legal work status, mostly from Asia and Africa, now work in poultry processing jobs held by Mexican immigrants before the state’s E-Verify law took effect in 2011.

But nearby in Gwinnett County, the Hispanic population grew 17 percent and the county just elected its third Hispanic state representative, Brenda Lopez of Norcross.

Soon after Pedro “Pete” Marin, a state representative from Duluth, was first elected in 2002, an ethics complaint was filed against him, charging that he was an agent of the Mexican government.

“I defended myself. I went to the ethics board and I said, ‘Hey, first of all I’m from Puerto Rico and second, I’ve never been to Mexico,’ ” he said.

Today, immigrants feel welcome in Gwinnett because it’s become very diverse, he said, with Asian immigrants from Vietnam and Korea joining Hispanic immigrants, mostly from Mexico and Central America.

But Marin, who spoke out against the E-Verify law, knows it’s not like that everywhere in the state. “Georgia needs immigrant labor to keep the economy growing,” he said. “Where are they going to come from?”

Georgia’s Chatham County, which includes Savannah, saw Hispanic growth dwindle a few years ago. Attendance fell at Hispanic outreach programs at the Savannah YMCA and its director complained that many Latinos were moving to “friendlier places.”

“People didn’t like the way they were treated and they started moving out,” said Alfonso Ribot, president of the Metropolitan Savannah Hispanic Chamber of Commerce.

Some of his members lost hundreds of employees overnight in fast-food and other service jobs, because the E-Verify law took effect and some immigrants started moving away.

Hispanic growth dropped from almost 1,100 in 2011 to less than 200 in 2013, but then bounced back to more than 600 in 2016. The county borders Jasper County, South Carolina, and Evans County, Georgia, which both lost Hispanic population between 2010 and 2016.

The turnaround in Chatham County came as Hispanic entrepreneurs, often U.S. citizens from Puerto Rico or legal immigrants from Cuba and South America, flowed north from Florida in search of opportunity, starting businesses and hiring people, Ribot said.

Declining School Enrollment

In Barbour County, where the workforce is aging and school enrollment is declining rapidly, officials have tried to reassure immigrants that they’re welcome.

“I’m glad they’re here. They’re hard workers,” said Eufaula Mayor Jack Tibbs, admitting that he hadn’t noticed the community much before the law took effect, except for seeing soccer games on community fields or people at the post office sending money orders home.

An exodus of young Hispanic families could help explain a school board report that said hundreds of babies born in Barbour County in 2006 never enrolled in public school in 2012.

The U.S. Department of Justice investigated whether the Alabama law violated the rights of all children to attend school without discrimination, as part of the lawsuit that overturned parts of the law. Statewide about 13 percent of Hispanic students withdrew from school in the months following the law, according to the investigation.

The SPLC got as many as 1,000 calls a week from immigrant parents in Alabama seeking advice about their children after the law passed, Tsu said.

“It was absolutely heartbreaking because they all had the same question,” Tsu said. “These were mothers asking how they could set up guardianship for their children if they were suddenly deported.”

‘We Decided To Stay’

Holy Redeemer Catholic Church in Eufaula draws about 75 people to a monthly Spanish-language Mass, using missals emblazoned with an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s patron saint. In 2011, Father David Shoemaker said, “We lost about half the people in a matter of two weeks. But it’s been stable since then.”

Once the more frightening parts of the Alabama law were struck down, some people returned, but not many, residents said.

An equipment operator from Chiapas, Mexico, said he thought of leaving with his wife and two young sons.

“We decided to stay. As long as you follow the law, you’re okay,” the man said, as his wife shopped for Mexican chayote squash at a local market and his sons nibbled frozen fruit bars known as paletas.

It’s not unusual for those who rode out the passage of immigration laws in the South to be glad they did, said Randy Capps, research director for the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute, despite new crackdowns and threats under the Trump administration.

“Some people left but by and large the ones who stayed are doing okay,” said Capps. “There are towns across the Southeast that are very dependent on immigrant labor, and the demand for them is high.”

Mendoza’s daughter, Maria, 21, said Eufaula remains a good place to live, and that local government officials had reassured immigrants that they’re welcome to stay.

“This is very much a family town. Everybody knows you. Everybody loves you. Everybody tries to help you,” she said.

Tim Henderson covers demographics for the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Stateline.