by Alex Nowrasteh

The political class is awash in self-serving theories to explain the rise of Donald Trump. Tim Carney blames differences of opinion between cosmopolitan elites and a nationalist base. Charles Murray sees answers in the disintegration of the white working class. Mark Krikorian and other nativists blame popular anger toward immigrants.

While some of these theories can explain portions of Trump’s appeal they are not the whole story. These are age-old grievances. Elites have always been indifferent to the rural poor. The working classes always wallow in self-pity and think they’re falling behind. And Americans claim to be a nation of immigrants, but we tend not to like the new-comers too much.

There are at least three under-explored factors that explain the rise of Trump in 2016 — and none of them are self-serving.

First, he’s a brilliant political entrepreneur. Trump created a political market based on his style much more than he exploited an existing one built on policy grievances. Sure, he tapped into latent populism that has always existed, but he grew it based on his personal brand — the same way he has managed his businesses.

Part of Trump’s brilliance was that he learned from Ross Perot, the last serious populist. Instead of creating a new political party, Trump opted for acquiring an existing one — something he might have learned during his brief attempt to get the Reform Party nomination in 2000.

Another sign of his acumen as a political entrepreneur was his timing which was only possible due to the second factor that explains his rise: The Republican Party was ripe for hostile populist takeover. Its vulnerability comes from its shift to a new regional power base — the South (east of Texas, south of the Mason-Dixon). The GOP has never been more Southern and less urban than it is now. Those two regions of the country have always been inclined toward populism. Trump has exploited that.

Fifty-seven percent of Trump’s delegates come from his sweep of six Southern states. Donald Trump won sixty percent of the delegates so far awarded by Southern states. Of the nine state primaries outside of the South, Trump lost five. Southerners are an increasingly vital component of the GOP’s base — making up for losses out west, in the mountain states, the Northeast, and the Midwest. The Southern states have a bigger say in the GOP as a result — and they are wielding it.

The country as a whole has never been less populist, but the Southern domination of the GOP has delayed that change inside of the party. A disproportionate number of populists arise in the South. The Jacksonians, Know-Nothings, George Wallace, Ross Perot, Mike Huckabee, Rick Santorum, Pat Buchanan, and now Donald Trump have either emerged from the South or built their power base there.

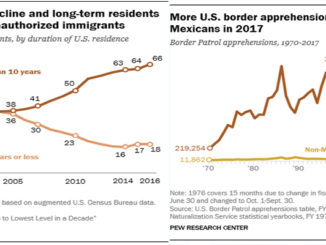

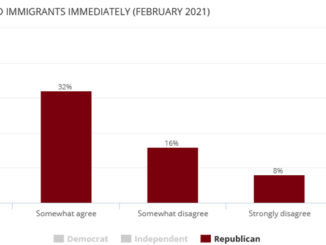

The third driver of this outburst of populism is that the tide has turned on one of the main arguments they care about: immigration. Voters are increasingly acknowledging what economists have long known: Immigrants don’t take our jobs or drive down American wages. According toGallup, 65 percent of Americans wanted less legal immigration in 1995. By 2015 that percentage crashed to 34 percent. During the same time, those who want more legal immigration climbed from 7 percent to a quarter of respondents.

Trump has won 46 percent of the GOP delegates but only 19 percent of them think immigration is the number one issue he should address as president. For the country as a whole, only 5 percent agree. The Southernness of Trump’s support can explain much of that discrepancy.

The populist Know-Nothing movement of the 1850s peaked right as European immigration was about to surge unchecked for 70 years. George Wallace ran for president after segregation was dead. Ross Perot’s anti-trade campaign peaked when NAFTA and the WTO were nearing completion. Trump’s populism is peaking now that popular opposition to legal immigration is about half of what it was 20 years ago.

Trump represents the last chance for nativists to turn around the popular opinion steadily getting friendlier toward immigration.

When the South’s dominance within the GOP and that region’s inclination toward populism are combined with lost policy causes, populism only requires a smart political entrepreneur and an enemy for his supporters to blame. Trump supplies the former, American “elites,” immigrants, and foreigners the latter.

Alex Nowrasteh is the immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity.