by Gerald F. Seib, WSJ

In August 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law a bill providing financial restitution to Americans of Japanese ancestry who were removed from their homes and placed in internment camps during World War II. The internment, he said upon signing the legislation, was “based solely on race” and constituted “a grave wrong.” He added: “Here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.”

Mr. Reagan is, of course, the ultimate modern-day Republican hero. Yet today, the current Republican presidential front-runner, Donald Trump, cites that same Japanese internment as justification for his proposal to temporarily ban Muslim immigrants from the U.S.

The juxtaposition of Mr. Reagan then and Mr. Trump now says much about how the immigration debate—and indeed the broader discussion about an outward-looking economic policy—has changed in the country generally and in the Republican party in particular, over the last three decades.

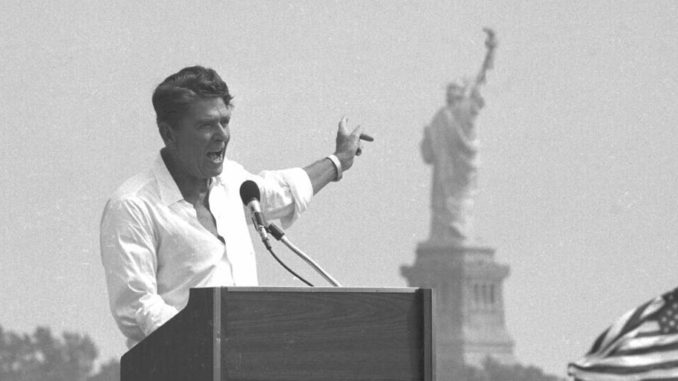

Mr. Reagan spoke eloquently and frequently about the virtues of immigration. Indeed, he announced his 1980 general election campaign with the Statue of Liberty in the background, and paid homage to the “golden door” to American immigrants the statue represented. He then returned to the statue for another famous Fourth of July speech six years later.

In the Reagan view, both the arrival of immigrants and the opening of borders to trade added to American economic strength. This year, Mr. Trump opened his campaign by focusing on illegal immigration and now has turned his sights on Muslim immigration. Meanwhile, he and several other Republican candidates, as well as all the two main Democratic presidential contenders, are opposing a new free-trade deal with Pacific nations, and a Congress controlled by Republicans appears increasingly unlikely to approve the trade deal until after the 2016 election.

The roots of these changed attitudes can be found in both a broad sense of insecurity, and in broad changes in the two major parties.

Part of traditional Republican support for a more tolerant view of immigration was a moral argument: American exceptionalism is rooted in its powerful belief that all people are created equal, and that America is the land of equal opportunity where all could thrive.

But there also was a strong economic argument—that in the aggregate, immigration amounted to an economic stimulant that ultimately was good for everybody. Unskilled immigrants did jobs few others wanted to do; skilled immigrants provided brains and entrepreneurial energy.

And in fact, that remains the argument advanced by immigration advocates. A nonpartisan organization called the Partnership for a New American Economy produces a regular stream of reports designed to show the economic boost immigrants provide. One this month on Toledo, Ohio, for example, reports that foreign-born households in Toledo have more than $242 million in spending power, and have contributed more than $31 million in taxes to state and local budgets. An earlier report said that more than one in four professional, scientific or technical service workers in Denver are foreign-born.

Those arguments still carry the day in the powerful business wing of the Republican party. But others are no longer convinced. Particularly to the middle-class, middle-aged voters who make up much of the Trump constituency, the combination of open trade and easy immigration seems to have more undermined than enhanced economic opportunity. They see advantages flowing to business leaders at the top of the income scale, and to the immigrant workers at the bottom, but aren’t convinced that they benefit as they struggle in the middle.

Democrats such as Sen. Bernie Sanders have been reinforcing that for a while; now some Republican candidates are as well.

Which leads to the other significant change in reaction to immigration and trade, which is the changing demographics of the two parties. For cultural more than economic reasons, more blue-collar and rural Americans have been moving toward the GOP since the Reagan presidency began. As a group, they identify less with the party’s traditional business wing, and are less swayed by its arguments on issues such as immigration and trade.

Indeed, in a new Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll, Democrats were more than twice as likely as Republicans to say that immigration helps America. A higher share of Democrats—56%–said free trade is good for America than the 48% of Republican who said free trade was beneficial. In addition, Republicans were only slightly more likely than Democrats to identify themselves as strong supporters of business interests.

Now, into this mix of economic insecurity, terror attacks have added a new layer of personal insecurity. Mr. Trump is taking advantage of that anxiety, though he didn’t create it.

“Fear is awfully powerful,” says Jimmy Kemp, son of former GOP vice presidential nominee and Reagan disciple Jack Kemp. “We need fearless leaders.”