by David Bier

Proponents of more restrictions on immigration—legal and illegal—talk a big game, suggesting more penalties for lawbreakers, more assets for the border, and more surveillance for the workforce. These, restrictionists say, will restore the rule of law. Yet while occupying the White House is new for them, the fact is that restrictionists largely dictated U.S. policy until recently. Not only have their ideas failed on their terms, they have backfired, creating more lawlessness than before.

Creating the Problem

Before the 1920s, America had no numerical restriction on the number of immigrants, so legal immigrants poured in. As a share of the population, total annual immigration flows were four times as great then as they are today. Restrictionists—members of the progressive wings of both parties—won the election of 1920 and immediately imposed a numerical cap. This reduced legal immigration by 80 percent, barring immigrants regardless of their health, wealth, or skills.

This fateful decision spawned all of the problems that restrictionists have blamed on their opponents ever since. “While legal immigration has been curbed to the extent that advocates of the new policy expected, that of the illegal—the ‘bootlegging’—kind has probably increased greatly,” the New York Times reported in 1925. “Some officials estimate that immigrants have been coming in clandestinely at a rate of at least 100 a day.”

Border patrols and deportations were increased to stop the flow of unauthorized immigrants, but they had little effect. “I’ve no doubt whatever that the man finally deported is back here,” the Assistant Secretary of Labor told the Times. “Easily 50 per cent of them return.” In July 1929, Congress gave in and provided “amnesty” or citizenship to the undocumented immigrants. Then, the Great Depression dried up demand for workers, temporarily resolving the issue.

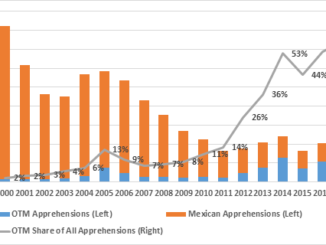

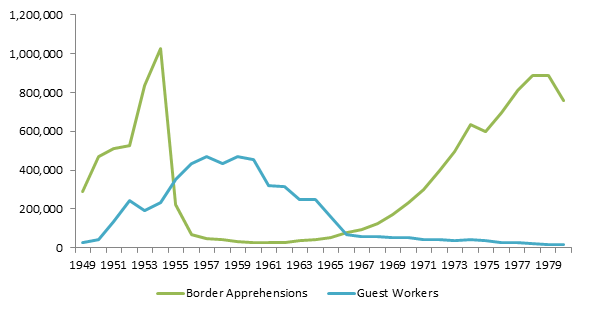

When the economy finally picked up again following World War II, illegal immigration returned. This time, Congress opted for a different approach: admit more workers legally. Under the Bracero guest worker program, illegal immigration almost vanished as the number of Braceros soared to almost a half a million in the early 1960s (Figure 1). Apprehended Mexicans were directed to border stations to receive cards to enter legally.

Figure 1: Aliens Apprehended at the Border and Low-Skilled Guest Workers (Braceros & H-2s)

Sources: Border Patrol; INS

But the restrictionists wouldn’t allow the fix to last. Over the vigorous objections from the Border Patrol, they cancelled the program under the guise of protecting U.S. workers. Over the next decade, the entire legal flow (and then some) was replaced with immigrants entering illegally. By the 1980s, over a million people were crossing the border each year.

A Parade of Phony Solutions

Restrictionists refused to accept responsibility for this chaos and demanded a new law to restrict the flow and fine employers who failed to check workers’ IDs. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan, who believed in more open legal immigration, signed the law, while extracting a legalization concession for unauthorized immigrants.

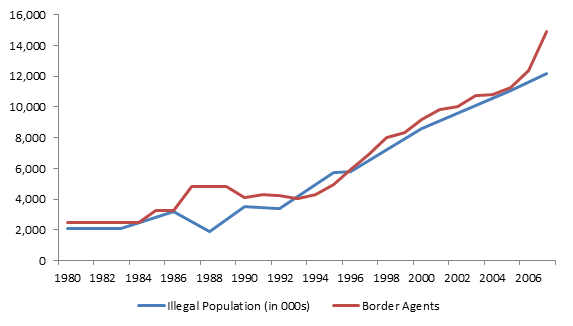

But the law backfired. Before 1986, workers—first as legal guests or later as illegal migrants—would return home at the end of each harvest, and as Figure 2 shows, the total illegal population in the country grew only very slowly throughout the decade. (The drop after 1986 occurred due to the legalization.) But with more border guards, it became too risky and costly to circulate each year. Instead of not coming at all, immigrants came and built their lives here. “If enforcement efforts had remained at pre-1986 levels,” concluded Princeton University’s Douglas Massey, “there would have been 5.3 million fewer net undocumented entries.”

Figure 2: Unauthorized Immigrant Population and Number of Border Patrol Agents

Sources: Warren and Passel (1980); Census Bureau (14 and up only, 1983); Congerssional Research Service (1986-1988); Pew Research Center (1990-2006); Border Patrol

The illegal population rose as fast as the number of border agents—both tripled between 1986 and 2000 (Figure 2). Not acknowledging their failure, restrictionists tried again, doubling the border agents over the next decade, which brought the level to ten times the amount in 1985. Immigrants continued to enter by the millions and the shadow population hit 12.2 million in 2007. As the cost of each crossing rose, cartels swooped in to capture the smuggling profits.

At the same time, the requirement that employers check IDs only created another black market in fake documents. Ignoring past failure, restrictionists doubled down in 2008, demanding a border fence and pressuring employers to use E-Verify, an employment verification system that checks Social Security numbers against federal databases. Rather than expunging the black market in jobs and documents, E-Verify has only ballooned yet another black market in identities.

Illegal immigration finally nosedived after the housing bubble burst, and the illegal population shrunk from 2007 to 2014. Meanwhile, ignoring the restrictionists, the Bush and Obama administration quietly resumed issuing many more work visas to Mexican workers. The result has been that just as many people were entering from Mexico in 2016 as in 2006, but most of them were doing so legally.

The Trump administration might want to undo this progress. With each new failure, restrictionists have never admitted that their core policy—restricting legal immigration—was the cause of all the others. Never mind that the Obama administration set records for deportations, it was never enough. Enforcement is the only tool in the restrictionist shed. Their many botched attempts to clean up their own mistakes is proof that they simply cannot fix the problem today.

David J. Bier is an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity.