by Pew Charitable Trusts

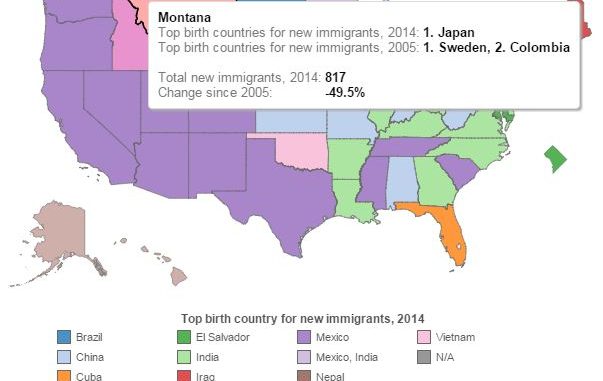

In 37 states, a country other than Mexico is now the most common country of origin for newly arrived immigrants, according to a Stateline analysis of census data.

The numbers reflect a steep decline in Mexican immigration since 2005 and point to a swift and dramatic shift toward Asia — especially China and India — as the dominant source of newcomers to the U.S.

A decade ago, Mexico was the most common country of origin for new immigrants — those in the country for a year or less — in most of the U.S., 33 states. By 2014, that had changed. Mexico was the main source of new arrivals in only a dozen states. And those from China or India were predominant in twice as many states.

“It is east of the Mississippi that shows a flip from Mexican to Indian, Chinese and other origins,” said William Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institution. “If this becomes a long-term trend, immigration will both spread further beyond the traditional gateways but also become more diverse in terms of country of origin.

” Much of the shift can be attributed to economic reasons. During the U.S. housing boom, still in full swing in 2005, many Mexican immigrants came to work in construction.But the housing bust and recession, plus stricter border enforcement and better job prospects in Mexico, reduced the flood to a trickle.

Meanwhile, a booming job market for people with technical and scientific skills has drawn increasing numbers of immigrants from India and China.

“The shift in top migration source countries is remarkable because it happened so rapidly,” the Migration Policy Institute wrote last year. MPI noted, however, that Mexico is still the country of origin for most immigrants in the U.S. (regardless of how long they’ve been here). There are 11.7 million Mexican immigrants in the U.S., compared to fewer than 5 million from India and China.

The U.S. Census Bureau figures show 428,000 new immigrants came from India and China in 2014, more than double the 2005 number. Meanwhile, the number of new immigrants from Mexico dropped by two-thirds, to 240,000. Their number had peaked in 2000, at about 875,000.

Visas for High-Skilled Workers

About 60,000 students from India and China came to study in the U.S. in 2014-2015, according a survey by the Institute of International Education. Many are likely to find jobs here after they graduate, with the help of visa programs for high-skilled labor.

In 2014, Indian immigrants held two-thirds of the more than 160,000 annual H-1B visas for high-skilled workers, while Chinese immigrants held 87 percent of the roughly 8,800 EB-5 visas for investors who create jobs. Together, Indian and Chinese immigrants held a third of the 150,000 L-1 visas for managers or skilled employees from overseas offices being transferred by their employer to the United States.

Though the employment visas are temporary, they are renewable and provide legal work status and the ability to compete for the 140,000 job-related green cards issued annually. Though no figures are available on how many temporary work visas are eventually converted to green cards and citizenship, they do provide a path for legal immigration.

“Since employment-based immigrants do not rely on U.S. family ties for their sponsorship, they become potent new seed immigrants for further future immigration by sponsoring their families to join them in the United States,” the MPI wrote.

Two states that have undergone a striking shift are Michigan and Illinois. Mexican-Americans have a long history in Detroit’s Mexicantown and in Chicago, the setting for Mexican-American author Sandra Cisneros’s bestselling semi-autobiographical 1984 novel, “The House on Mango Street.”

In Illinois, new arrivals from Mexico plummeted 71 percent from 2005 to 2014, to about 11,300, while the number of new immigrants from India nearly tripled, to about 17,900.

“I had no idea,” Cisneros said of the shift. “Mexican migration has been happening [in Chicago] since the middle of the 19th century. We may have tapered off, but our history goes back a long way.”

Michigan’s new arrivals from Mexico dropped by half, to about 3,700, during that time. Meanwhile, those from China nearly quadrupled, to 7,500, making China the top country of origin for new immigrants to Michigan, followed by India at about 6,900.

In Florida, the number of newly arrived Mexican immigrants declined from 34,000 in 2005 to about 7,700 in 2014, a 77 percent drop. Meanwhile, the number of new immigrants from Cuba more than doubled, to 54,000. During the same period, Venezuela became the state’s second most common country of origin, with 15,000 new immigrants.

Educated Arrivals

Today’s newest immigrants are more likely to arrive legally and with college degrees than a decade ago, said Jeanne Batalova, a senior policy analyst at MPI who is working on an upcoming report that will highlight the financial advantages of having skilled immigration for state and local government.

One reason is stepped-up border enforcement, which has discouraged unauthorized, unskilled laborers from crossing the southern border of the U.S. in search of work.

Illegal Mexican immigration peaked in 2007 and has since dropped by a million, to 5.6 million, according to a November Pew Research Center report (Pew funds Stateline).

Even states along the border and in the West, which have long been destination points for Mexican immigrants, experienced big drops. Between 2005 and 2014, the number of new immigrants from Mexico dropped by half in Texas, by two-thirds in California, and by 80 percent in Arizona and New Mexico.

In California, the number of new Chinese immigrants tripled from 2005 to 2014, to more than 48,000, making them the second largest group of newcomers after Mexicans. Assembly District 49, east of Los Angeles, became the state’s first majority Asian district in 2012, mostly because of new arrivals from China, said Hong Kong native Ed Chau, the district’s assemblyman.

New arrivals may be older businessmen, often in business with China, while younger arrivals tend to work in engineering and science, Chau said. One thing they have in common is a need for interpreters and translated materials. Chau said many new immigrants call his office for English language help with everything from driver’s license applications to state business regulations. Chau has proposed three laws to provide more foreign-language help in health care, courts and voting.

In 2000, New York had one majority-Asian Assembly district, in Flushing, Queens. In 2012, it added two more, one in Queens and the other in nearby Brooklyn. A state Senate district, in Queens, is now also majority Asian, said Jerry Vattamala, an attorney for the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund in New York.

In 2014, the most common country of origin for New York’s new immigrants was China. In 2005, the largest group of newcomers was from the Dominican Republic.

“With all the people coming from China and India, mostly, that Flushing area is really booming and businesses are doing well,” Vattamala said. “It’s really amazing what’s going on there.”

Vattamala said gaining citizenship can be a long, frustrating road for H-1B visa holders, who often wait a decade or more to get a green card. They may be forced to return to their native countries if they lose their jobs, and therefore the visa, before they move up the lengthy waiting list.

“Most would like to stay,” he said. “They’ve made a life here, they have kids here, their kids are in the schools and they’re acclimated to the culture.”

The share of college graduates among recent immigrants rose from 27 percent in the early 2000s to 44 percent a decade later, Batalova said, as college-educated Asian newcomers rose and unauthorized laborers from Mexico declined. And the percentage of recent Latin American immigrants with a college degree doubled, from 10 to 21 percent, she said.

“A greater share of recent arrivals is highly skilled, and that’s a good thing, as long as they are employed in ways that use their abilities and not in low-skill jobs,” Batalova said.

Changes in Mexico

Legal Mexican migration has dropped off, too, as Mexico has changed.

Batalova said Mexicans aren’t having as many children, they are more educated, and the country’s unemployment rate has declined.

Meanwhile, Asians are likely to keep coming as long as the U.S. economy continues to improve and jobs for college-educated immigrants are created. “They will certainly help us make greater connections to a wider global economy given the variety of countries they are coming from,” said Brookings’ Frey.