by Alex Nowrasteh

One popular argument against a legalization, or amnesty, of unlawful immigrants is that it will merely incentivize future unlawful immigration. Unlawful immigrants will be more likely to break immigration laws because they will eventually be legalized anyway, so why bother to attempt to enter legally (ignoring the fact that almost none of them could have entered legally)? This claim is taken at face value because the stock of unlawful immigration eventually increased in the decades after the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) that amnestied roughly 2.7 million.

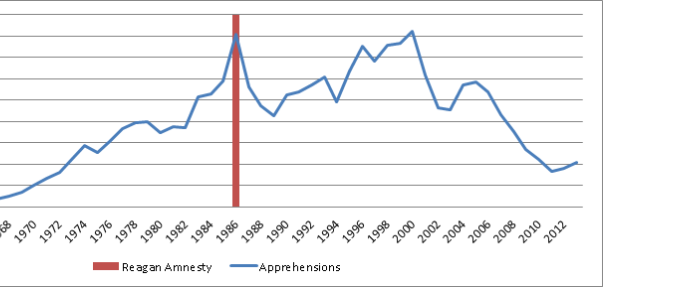

However, that doesn’t prove that IRCA was responsible for the increase in the stock of unlawful immigrants. The stock of unlawful immigrants may have been increasing at a steady rate prior to the amnesty and that rate may have just continued after the amnesty. Measuring the flows of unlawful immigrants is the best way to gauge whether the 1986 Reagan amnesty incentivized further unlawful immigration. If the flows increased after IRCA, then the amnesty likely incentivized more unlawful immigration. The number of annual apprehensions of unlawful immigrants on the Southwest border is a good way to approximate for these cross-border flows.

It’s perfectly reasonable to think that an amnesty of unlawful immigrants could increase their numbers in the future. There are at least two ways this could occur. The first is through knowledge of an imminent amnesty. If foreigners thought Congress was about to grant legal status to large numbers of unlawful immigrants, then some of those foreigners may rush the border on the chance that they would be included. Legislators were aware of this problem, which was why IRCA did not apply to unlawful immigrants who entered on January 1st 1982 or after. IRCA had been debated for years before passage and Congress did not want to grant amnesty to unlawful immigrants who entered merely because they heard of the amnesty. To prevent such a rush, subsequent immigration reform bills have all had a cutoff date for legalization prior to Congressional debate on the matter.

Even with the cutoff date, some recent unlawful immigrants would still be able to legalize due to fraud or administrative oversights. An unlawful immigrant who rushes the border to take advantage of an imminent amnesty still has a greater chance of being legalized than he did before, so legalization might be the marginal benefit that convinces him to try. This theory of a rush of unlawful immigrants prior to an imminent amnesty is not controversial.

A bolder claim is that IRCA incentivized the unlawful immigration that followed its passage. As this theory goes, the benefits of immigrating illegally are higher because they assume that at some point in the future they will be legalized just like the previous waves of unlawful migrants were (there were also small amnesties in 1929, 1958, and 1965).

This academic paper by Pia M. Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny analyzed the apprehensions of unlawful immigrants prior to IRCA’s passage and a decade after to see if there was a marked increase in apprehensions. After the amnesty went into effect, apprehensions dropped significantly and then rebounded by the mid-1990s. They concluded that apprehensions returned to their pre-IRCA trend line and IRCA neither increased nor reduced the pace of unlawful immigration. This other working paper analyzed apprehensions data from 1977-2000 and found that IRCA was associated with a decline in apprehensions.

Many studies attempted to find how IRCA affected flows of unlawful immigrants immediately after the amnesty went into effect. They are of limited long-term use but worth mentioning. In 1990, Woodrow and Passel also found that IRCA did not affect the annual number of unlawful immigrants compared to the years prior to the amnesty. Two other studies found small temporary declines in the flow of unauthorized immigrants. This paper, based on surveys of Mexican migrants from seven communities in Mexico from 1987-1989, found that there was no consistent change in the probability of an unauthorized immigrant making his or her first trip to the United States as a result of IRCA.

One possible reason why post-IRCA apprehensions were steady is that increased border security under IRCA might have stopped circular migrant flows across the border – by locking unlawful migrants inside of the United States. Without IRCA, many of them otherwise would have left and likely returned in the future and been apprehended, thus increasing those numbers. Because IRCA increased the risks and costs of crossing the border due to a surge in border security, the stock of unlawful immigrants rose while the annual flows moderated. The evidence for this is that the apprehensions of women and children increased after IRCA, likely because they were coming north to reunite with their husbands and fathers who were working in the United States. In other words, by increasing border security or the benefits of settlement through an amnesty, IRCA may have incentivized unlawful immigrants to settle permanently in the United States rather than migrating temporarily for work. IRCA may not have affected apprehensions very much but it likely changed settlement patterns.

Below is the data of annual apprehensions on the Southwest border.

Source: Customs and Border Protection

Source: Customs and Border Protection

The pre-IRCA annual flows of unauthorized immigrants peaked in 1986.

Source: Customs and Border Protection

Post-IRCA, the annual flows of apprehended unlawful immigrants on the Southwest border declined before rising again around the dotcom bubble and then crashed along with the housing sector. Does not look like IRCA caused a sustained increase in unauthorized immigrant flows.

Source: Customs and Border Protection

Source: Customs and Border Protection

An imminent amnesty may temporarily increase the flow of unlawful immigrants. Legalization or amnesty bills try to account for that by excluding recent unauthorized immigrants from the legalizations. However, there isn’t any good evidence that amnesties increase the flows of unlawful immigrants after the amnesty goes into effect. Economic and demographic factors played a much larger role in influencing the decision to immigrate rather than the 1986 amnesty. Ironically, IRCA likely produced to a longer settled unlawful immigrant population that subsequent increases in border security and the 3/10 year bars reinforced.

Alex Nowrasteh is the immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity.