by Susan Dynarski

Public schools are increasingly filled with black and Hispanic students, but the children identified as “gifted” in those schools are overwhelmingly white and Asian.

The numbers are startling. Black third graders are half as likely as whites to be included in programs for the gifted, and the deficit is nearly as large for Hispanics, according to work by two Vanderbilt researchers, Jason Grissom and Christopher Redding.

New evidence indicates that schools have contributed to these disparities by underestimating the potential of black and Hispanic children. But that can change: When one large school district in Florida altered how it screened children, the number of black and Hispanic children identified as gifted doubled.

That district is Broward County, which includes Fort Lauderdale and has one of the largest and most diverse student populations in the country. More than half of its students are black or Hispanic, and a similar proportion are from low-income families. Yet, as of 10 years ago, just 28 percent of the third graders who were identified as gifted were black or Hispanic.

In 2005, in an effort to reduce that disparity, Broward County introduced a universal screening program, requiring that all second graders take a short nonverbal test, with high scorers referred for I.Q. testing. Under the previous system, the district had relied on teachers and parents to make those referrals.

The economists David Card of the University of California, Berkeley, and Laura Giuliano of the University of Miami studied the effects of this policy shift. The results were striking.

The share of Hispanic children identified as gifted tripled, to 6 percent from 2 percent. The share of black children rose to 3 percent from 1 percent. For whites, the gain was more muted, to 8 percent from 6 percent.

Why did the new screening system find so many more gifted children, especially among blacks and Hispanics? It did not rely on teachers and parents to winnow students. The researchers found that teachers and parents were less likely to refer high-ability blacks and Hispanics, as well as children learning English as a second language, for I.Q. testing. The universal test leveled the playing field.

Multiple factors could be at work here: Teachers may have lower expectations for these children, and their parents may be unfamiliar with the process and the programs. Whatever the reason, the evidence indicates that relying on teachers and parents increases racial and ethnic disparities.

The gifted program was not a panacea. The researchers found that the district’s specialized classes had little effect on the academic achievement of students who had been specifically identified as gifted, through I.Q. tests. They are not sure why. In Broward County, as in many other places, classes for the gifted use the same curriculum and textbook as other classes. Teachers in the classes for the gifted were required to have a special certification and were encouraged to supplement the curriculum.

But the separate classes did produce enormous, positive effects for children who were high achievers but did not qualify based on the I.Q. test. A quirk in the rules helped these children: Broward requires that schools with even one child who tests above the I.Q. cutoff devote an entire classroom to gifted and high-achieving children.

Since a school in Broward rarely had enough gifted children to fill a class, these classrooms were topped off with children from the same school who scored high on the district’s standardized test. These high achievers, especially black and Hispanics, showed large increases in math and reading when placed in a class for the gifted, and these effects persisted.

What is more, while many children in the gifted program gained enormously, Mr. Card and Ms. Giuliano found no negative effects for those who remained in regular classes. Yet all of these gains came at little financial cost. The enhanced classes were no more expensive than the standard ones. They were the same size as regular classes, and teachers in the classes for the gifted were paid no more than others.

This story has twists, though.

Despite these positive results, Broward County suspended its universal screening program in 2010 in a spate of budget cutting after the Great Recession. Racial and ethnic disparities re-emerged, as large as they were before the policy change. In 2012 the district reinstated a modified version of universal screening, but it has not achieved the same results. Using data from the Florida Department of Education, I calculate that 8 percent of white students in Broward County are classified as gifted. That is twice the rate for Hispanics and four times the rate for blacks, much higher ratios than under universal screening.

One problem with the new screening program is that the previous nonverbal test, which psychologists say they believe to be culturally neutral, has been replaced with one that relies more on verbal ability. Another is that Broward parents and teachers can still influence whether children are selected. While school psychologists test students at no cost, parents can hire a private psychologist to test a child, at a cost of $1,000, and are allowed to pay for multiple tests, should a child not meet the I.Q. requirement on the first try. Mr. Card and Ms. Giuliano found evidence suggesting that private testing gives an advantage to upper-income families, who tend to be white.

Many researchers worry that I.Q. tests are biased against low-income and nonwhite children, and some recommend a more holistic approach that includes teacher referrals. But referrals produce biases, too. Matthew McBee, a psychologist who edits The Journal of Advanced Academics, which focuses on gifted education, recently called referrals “the elephant in the room,” a largely unexamined source of racial and ethnic bias in the identification of gifted children.

Given these problems, we might be tempted to abandon these programs for gifted and high-achieving children entirely. After all, distinguishing between gifted students and everybody else could lock some children, especially disadvantaged children, into a long-term track with low expectations that, too often, are self-fulfilling.

But without some method of identifying talented students, disadvantaged children may fall even further behind those from affluent families, whose parents can afford niceties like private tutors, Kumon math courses and coding camps. Low-income parents just can’t afford these extras.

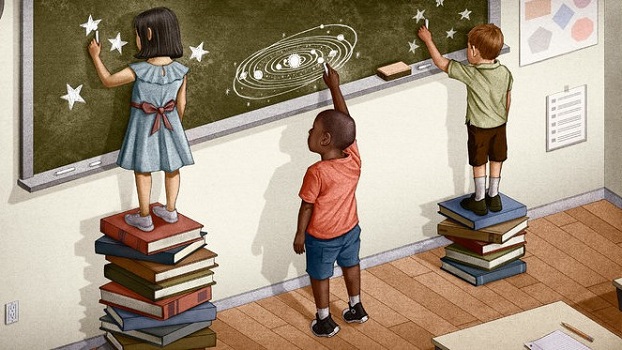

That’s why the research in Broward County is so important. It shows that there is a fairer way to identify gifted children, and that placing each school’s gifted and achieving students in advanced classes can shrink, rather than expand, racial and ethnic differences in achievement. Universal screening, with a standardized process that does not rely on teachers and parents, can reveal talented, disadvantaged children who would otherwise go undiscovered. Challenging classes for these children can help them to reach their full potential.