Coastal elites’ won’t be hardest hit if the President nixes the trade agreement.

Donald Trump’s strategy to brand his political opponents swamp creatures may be what got him to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. But it’s hard to see how it can continue to succeed when, in his zeal to zero out a trade deficit with Mexico, he has turned his sights on an important engine of growth in red-state America.

At a private luncheon with Republican senators last Tuesday, Mr. Trump reportedly shared his North American Free Trade Agreement negotiating strategy. According to Inside Trade, which spoke to senators who attended the gathering, the president believes that by issuing a notification of his intent to leave Nafta—which would trigger a six-month waiting period before the actual exit—he can force Mexico and Canada to make the concessions he wants.

“The president said there was no way to get the changes we need unless we get out, then have six months to negotiate,” one GOP senator told the Washington-based trade publication. Mr. Trump reportedly did not say what those concessions are. The only clear goal, according to one unnamed senator, is ending the trade deficit with Mexico.

The “walk-away” strategy worries Sen. Pat Roberts of Kansas, who told Inside Trade “that if you start the clock on NAFTA [withdrawal] that’s going to send very bad signals throughout the entire farm economy.” America’s farmers and ranchers exported $17.9 billion to Mexico in 2016.

Mr. Roberts added: “And then to restitch that and put it all back together it’s like Humpty Dumpty. You push Mr. Humpty Dumpty trade off the wall and it’s very hard to put him back together.”

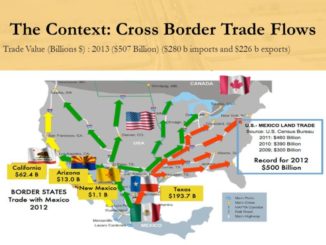

Almost five million U.S. jobs rely on trade with Mexico, including jobs in auto manufacturing, auto parts, railroads, heavy equipment, machinery, oil and gas, steel fabricating, farming, ranching and food processing, as well as marketing, design, insurance, financial services and intellectual-property.

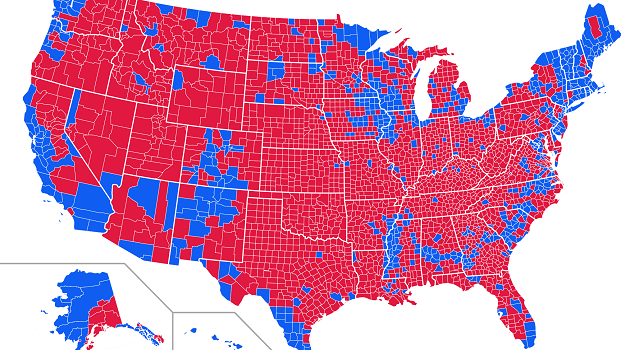

The pushback against Mr. Trump’s Nafta assault is not coming from “coastal elites” contemptuous of what they refer to as “flyover country.” It’s coming from the “flyover” industrial and farming heartland itself, which has the most to lose.

Writing in the Kansas City Star on Tuesday, Kansas City Southern Railway Co. president and CEO Patrick Ottensmeyer noted that Mexico is Missouri’s second-largest export market and Kansas’ largest export market. Almost 100,000 Missouri jobs and 50,000 Kansas jobs depend on trade with Mexico. Exports from the two states to Mexico “have increased by more than 550 percent under NAFTA,” wrote Mr. Ottensmeyer.

On Wednesday some 80 food and agricultural business groups sent a detailed letter to Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross warning the administration of the risks of withdrawal. “Contracts would be cancelled, sales would be lost, able competitors would rush to seize our export markets, and litigation would abound even before withdrawal would take effect,” the letter said.

The auto industry is particularly vulnerable if Humpty shatters. On Thursday American auto makers, parts suppliers and dealers announced that they had “joined together for the first time in their collective history” in a coalition called Driving American Jobs that is designed to defend Nafta. The group noted that one million more vehicles were made in the U.S. in 2016 than in 1993, the year before the implementation of Nafta, which Mr. Trump calls “the worst trade deal ever made.”

American protectionists say Mexico steals jobs, but that’s fake news. According to a report by a Mexico-City-based economic consulting firm, the net creation of jobs in Mexico using American foreign direct investment is minuscule compared with gross job losses in the U.S. Manufacturing is interconnected on the continent so employment on both sides of the border tends to move in tandem. When the region’s economy does well, North American job opportunities expand and vice versa.

Mexican companies also create American jobs. Grupo Alfa ’s refrigerated-foods division buys American meat, supporting some 40,000 jobs north of the border. In Alfa’s aluminum-auto-parts business, 4,500 of its 13,000 North American employees are Americans. More than 50% of its raw materials are sourced in the U.S.

Mexico has said it is eager to modernize Nafta. But with a Mexican presidential election in July 2018 there is no way the government is going to bow to the managed-trade demands of Mr. Trump, whose image inside Mexico is no better than that of James K. Polk, who presided over the Mexican-American War.

Mexico says that in a post-Nafta world it would buy its grain and meat in South America, prompting one wise senator to tell Inside Trade, “We’re not in as strong a position as [Trump] thinks we are.” As to manufacturing, companies are likely, at least initially, to pay any new U.S. tariff and pass the cost on to American consumers, essentially handing them a tax increase. Not exactly what Mr. Trump promised Middle America.