In 2009, 48 states and the District of Columbia joined together to launch the Common Core State Standards Initiative. Their mission: to develop common academic standards in English and mathematics that would help ensure that “all students, regardless of where they live, are graduating high school prepared for college, career, and life.”

It was a laudable goal, but one that 15 years of federal mandates had failed to accomplish. Tasked by the federal government with bringing all students to “proficiency,” most states set undemanding standards, and the quality of their assessments varied widely. The Council of Chief State School Officers and the National Governors Association set out to raise and unify K–12 standards through the Common Core initiative.

Common standards call for common assessments. Late in 2009, the Obama administration, through its Race to the Top (RttT) program, announced a competition for $350 million in grant money to spur the development of “next-generation” tests aligned to the Common Core. Six consortia formed to submit applications for funding, but mergers left just two seeking to develop the new assessments. The government awarded four-year grants to the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC) and the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC).

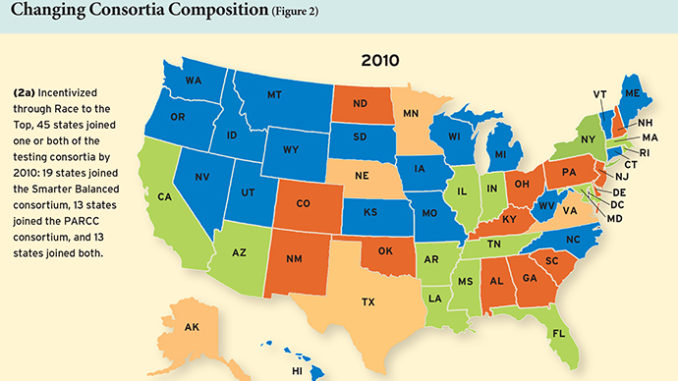

Earlier in 2009, also through Race to the Top, the administration had offered $4.35 billion in funding through a competitive grant program designed to encourage states to enact the feds’ preferred school-reform policies—including the adoption of better standards and assessments. Most states were willing to sign on to Common Core and the aligned tests to improve their chances of winning a grant. By 2011, one year after the standards had officially been released, 45 states plus the District of Columbia had signed on to the standards and joined one or both of the assessment consortia.

But as states moved to implement the new standards and assessments, controversy began to swirl around the reforms. Although the Common Core standards drew criticism from parents and pundits, from the right and the left, most states stood firm in embracing them. Yet loyalty to the consortia’s assessments has proved much weaker. The number of states planning to use the new tests dropped from 45 in 2011 to 20 in 2016.

This presents a puzzle: why have so many states abandoned the consortia, even as the standards on which they are based continue to live on in most places?

Consortia Beginnings

Proponents of the next-generation assessments argued that such tests would enable educators to track progress toward the higher-order thinking skills—such as critical thinking, communicating effectively, and problem solving—that the standards emphasized. By collaborating through a consortium, states would be able to produce a higher-quality assessment, at lower cost, than what they could achieve on their own. The Common Core–aligned tests would also allow policymakers to use the same measuring stick to evaluate student progress in different states.

In 2010, the PARCC and SBAC consortia reported having 26 and 32 member states, respectively, representing diverse political environments. Only Alaska, Minnesota, Nebraska, Texas, and Virginia declined to join by the end of that year. Alaska, whose state standards were closely aligned with the Common Core, affiliated with SBAC in 2013. Minnesota adopted only the English language arts standards and so did not join a consortium. Nebraska, Texas, and Virginia never adopted Common Core or affiliated with a consortium.

The two consortia took similar approaches to assessment design. Both sought to develop state-of-the-art assessments that focused on problem solving and the application of knowledge and moved away from former tests’ reliance on multiple-choice questions and the testing of factual recall. The new tests would be administered by computer, reducing the time needed to evaluate results and

thus enhancing the usefulness of this information for teachers and schools. And finally, both consortia committed to transparent communication of student-achievement data to stakeholders.

The consortia differed in a few particulars. SBAC adopted a computer-adaptive test model, in which the difficulty of the assessment would vary according to students’ responses, and it made high-school assessments optional for the states. PARCC required all member states to use the same test vendor (Pearson) to implement the assessments, while SBAC allowed its members to choose their own.

State Exits Increase

State participation in the consortia declined just as implementation of the new standards and tests was set to begin. The pace of withdrawals quickened over time, particularly for PARCC, which five or six states left every year between 2013 and 2015 (see Figure 1). As of May 2016, just six states planned to implement the PARCC-designed assessment in the 2016-17 academic year. SBAC also faced attrition but fared better and still retains 14 states that plan to use the full test. (That figure includes Iowa, where a legislative task force has overwhelmingly recommended the SBAC assessment, though as of early 2016 state officials had yet to formally accept the recommendation.) By early 2016, 38 states had left one or both consortia, short-circuiting the state-by-state comparability that the tests were designed to deliver (see Figure 2).

Political Resistance

Much of the opposition to the Common Core–aligned assessments—particularly among parents—is related to a broader backlash against the amount of testing students now undergo and a perception that it diminishes instructional time and encourages “teaching to the test.” While proponents argue that the Common Core standards and assessments represent an improvement over those most states used under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, many have come to see Common Core as simply NCLB 2.0.

Criticism from both ends of the political spectrum has buffeted Common Core. On the right, many Tea Party adherents and others view the initiative as a dangerous or even unconstitutional expansion of federal control of education. It was not difficult for opponents to cast Common Core as a federal initiative, given 1) the Obama administration’s use of RttT incentives (and later, waivers to NCLB requirements) to encourage states to adopt the standards and 2) the administration’s funding of the consortia. While the Common Core initiative is actually a product of state cooperation, the 2014 Education Next survey found that 64 percent of respondents who had heard of Common Core believed that “the federal government requires all states to use the Common Core standards” (see “No Common Opinion on the Common Core,” features, Winter 2015). To many conservatives, the standards have become a powerful and threatening symbol of big government, causing critics on the right to dub it “Obamacore.”

Furthermore, the Common Core assessments emerged onto the public agenda in the wake of revelations of widespread privacy violations by the National Security Agency, playing into heightened fears about data mining. In this context, conspiracy theorists like Michelle Malkin could whip up public fear with her March 2013 National Review column, “Common Core as Trojan Horse: It’s time to opt out of the creepy federal data-mining racket.” The 2014 Education Next survey found that 85 percent of Americans who had heard of Common Core erroneously believed that the federal government would receive detailed data on individual students’ test performance.

On the left, some of the opposition to Common Core and its assessments is related to broader resistance to high-stakes testing, the linking of student scores to teacher evaluations, and other reform measures such as school choice, which some see as “corporate school reform.” Diane Ravitch of New York University, a prominent critic of Common Core, wrote in 2015, “The reason to standardize education across the nation is to create an attractive business climate for entrepreneurs.” The business community has indeed been among the most vocal supporters of Common Core, arguing that higher academic standards are imperative to ensuring that the American economy has the high-quality workforce necessary to compete in the global marketplace. The association of big business with Common Core has fueled Americans’ long-standing antipathy toward the power elite. Some have even argued that Common Core is a scheme intended to increase the profits of large companies such as Pearson and Microsoft. Still others see the initiative as part of an even larger conspiracy to dismantle public schools and privatize education. In this view, public schools will struggle to meet the higher standards—and not receive the resources with which to do so—and this will open the door to the expansion of charter schools, private-school voucher programs, and online virtual learning. As Susan Spicka, a Pennsylvania parent, wrote, “[H]igh stakes [tests] are being used as a tool by corporate school reform advocates to put public schools in the hands of private businesses, whose goal is to profitize our children, not to educate them.”

These criticisms from the extremes of the political spectrum have not persuaded many states to drop Common Core, which is bolstered by a large and bipartisan group of policymakers and other elites. The consortia-designed assessments, however, have not fared so well, because their implementation became intertwined with new, controversial teacher evaluations and school accountability measures.

Assessments Meet Accountability

Proponents of Common Core made their case by arguing that the standards would improve public education and eventually strengthen the workforce: they would ensure that all high-school graduates were “college and career ready,” that America remained “globally competitive,” and that all students had access to a rigorous education “regardless of where a child lives or what their background is.” But universal standards, on their own, accomplish none of these goals. In order to effect change, they must be paired with aligned testing that gives reliable information on which children are making appropriate progress in school, and which are not.

Standards coupled with assessments can thus provide the basis for holding students, teachers, and schools accountable for student learning in K–12 education. In the case of Common Core, the assessments were more rigorous and established a higher bar than did most traditional state assessments. Furthermore, the new assessments emerged at a time of rapid upheaval for K–12 accountability, when school districts were introducing enhanced consequences for teachers, principals, and schools that failed to improve student achievement.

School administrators, teachers, and their unions were initially quite supportive of the Common Core and its potential to improve teaching and learning. The aligned assessments, however, became politically charged, because they were introduced simultaneously with new teacher-evaluation systems that used student-achievement data as a significant criterion. Educators contended that states were tying the employee-evaluation process to the new standards and assessments too quickly, before teachers and students had been able to put the Common Core into practice. Many feared that the new assessments would result in arbitrary or unfair personnel decisions. Forty-three states, D.C., and Puerto Rico had received waivers from NCLB requirements, however, and had little choice: the waiver program essentially required them to develop new teacher evaluations, even as they rolled out the new standards.

A 2014 PDK/Gallup poll found that 76 percent of teachers continued to support the goals of Common Core, but only 9 percent supported using those test scores to evaluate teachers. As Sandi Jacobs, managing director of state policy for the National Council on Teacher Quality, said, “There wasn’t enough concern about how these things [the Common Core and teacher evaluation] were running down the path together until the tests became an issue.”

The unions, too, continued to support the standards but opposed the consortium-designed assessments because of their link to teacher evaluations.

Hindsight suggests that implementation of the assessments might have been more successful, and politically sustainable, if the new standards and tests had not been connected to states’ K–12 accountability systems, and especially teacher evaluations, until key stakeholders had become acclimated to them. But, under pressure from the federal government, most states tied the new assessments to accountability at a time when teachers’ practice and local curriculum had not yet become fully aligned with new expectations.

As backlash against the assessments has swelled, even support for the Common Core standards has begun to dwindle. In 2013, the Education Next poll showed 76 percent of teachers and 63 percent of parents supported the standards. By 2015, the same poll found that just 40 percent of teachers and 47 percent of parents supported them.

Implementation Challenges

States varied tremendously in their readiness to implement the consortia-designed assessments, which represented a significant shift from most states’ prior assessment systems. The new assessments set forth more-challenging proficiency benchmarks for students and required substantial investments in technology as well as increased testing time. Lamenting schools’ preparedness for the transition, one teacher foreshadowed the implementation challenges ahead by tweeting, “We start testing on standards we’re not teaching with curriculum we don’t have on computers that don’t exist.”

State education agencies and districts struggled to finance and manage the implementation of the new standards and assessments. The American Association of School Administrators argued that states needed to “slow down to get it right,” while Dennis Van Roekel, then president of the National Education Association, charged that implementation had been “completely botched.” Teachers complained of insufficient professional development and lack of quality curriculum. States and districts confronted massive technology failures, owing to insufficient preparation and contractors who failed to deliver the needed technology upgrades. Parents revolted as the consortia set testing times and proficiency benchmarks that they viewed as developmentally inappropriate and, in some cases, a waste of resources. States also varied widely in how well they communicated with educators, parents, and the general public about the new tests.

Support from the Wrong Places

The Common Core standards and their aligned assessments drew many supporters from the federal and state governments, from the philanthropic community, and from reform advocates, but most members of these groups do not have a personal stake—a vested interest—in what happens in schools at the ground level. Therefore, their support alone is not enough to sustain education reform over time. Federal and state policymakers sometimes embrace high standards and quality assessments in principle, but when they experience intense pressure from interest groups and the public, their support is likely to falter. Indeed, many former supporters of Common Core, including Republican governors Bobby Jindal of Louisiana, Chris Christie of New Jersey, and Mary Fallin of Oklahoma, have withdrawn support of the standards in the face of political opposition from conservative interest groups, teachers unions, and swarms of parents and other voters.

Advocacy organizations such as Achieve and the Collaborative for Student Success can help build political support, but in the case of Common Core, efforts have largely focused on lobbying policymakers, not building the kind of broad-based coalitions needed to reengineer the K–12 system around high standards, quality assessments, and accountability for results. Parents and other community members were often left to learn about the standards and assessments via their social networks, where ill-informed but powerful negative interpretations of the reforms circulated through social media and were passed along by teachers, or at the dinner table. And the standards won few advocates among the parents and guardians who struggled to help their children navigate the new expectations with little guidance to support their efforts.

Philanthropists who supported Common Core also underestimated what would be necessary to support the transition to higher standards. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation invested $230 million in design, implementation support, and advocacy. But, as Jay Greene of the University of Arkansas argues, foundations can’t compel change, because the resources they invest are so small relative to the budgets of the organizations they seek to affect, and any effort to impose a solution will draw out opponents who are far more powerful and vested than the foundations themselves. Greene finds that philanthropic investments have the greatest impact when they create constituencies that advocate for change, but this didn’t happen in the case of Common Core.

The lack of vested stakeholder support had particularly acute consequences for the assessments. Standards for student learning are not likely to draw many opponents when they are just words on a page, because they threaten no one. But when policymakers seek to hold students, teachers, and schools accountable for those standards using aligned assessments, they are far more likely to stimulate opposition from those who have much to lose.

Saving the Standards

In many states, however, policymakers who supported Common Core took a different tack: they sought to diffuse opposition to the standards by withdrawing from the consortia-designed assessments, perhaps the most visible and consequential elements of the new accountability systems. As Mike Cohen, the president of the advocacy organization Achieve, observed: “The new SBAC and PARCC assessments have Common Core written all over [them]—federally funded, part of a national effort … In many states where opposition to the Common Core emerged, the compromise was to hold on to the standards and get rid of the aligned tests.” Mitchell Chester, commissioner of education in Massachusetts, agreed, saying, “Often, as in Florida and Louisiana, it was governors making a political calculus” and concluding that the cost of staying in the consortia was too high.

Abandoning the assessments did not change the opinion of the most strident opponents of the standards. Indeed, critics of Common Core were quick to point out that the compromise agreements negotiated in Louisiana and Massachusetts did not stop the implementation of Common Core (both states will continue to use some elements of the consortia-designed assessments). But the moves may mollify more moderate groups, whose commitment to the issue was never firmly rooted.

Looking Ahead

Sustaining voluntary multistate efforts like the consortia presents considerable challenges. Faced with declining membership, both consortia have contemplated changes to their assessments to manage the growing political pushback against the Common Core and standardized testing in many states. The two consortia have worked to address concerns expressed by teachers, schools, and district administrators by reducing testing time, shortening the time periods over which tests are administered, limiting the number of units covered, and reducing the number of required testing sessions.

In late 2015, PARCC announced new flexibility for states, giving them more control over test-vendor selection and the option of using the complete assessment or specific items (or blocks of items) to customize their own assessments. Massachusetts and Louisiana have both moved forward with “hybrid” state tests that combine consortia- and state-designed assessment items. Mitchell Chester believes such a hybrid approach is likely to become more prevalent in the future, noting that this model “addresses both the political problems and the customization needs in states.” The hope is that a block of test items could be developed that all states could use for comparability purposes—a “core of the Core.” Can such an approach produce assessments that adequately align with the Common Core? Can it provide the kind of interstate comparability that proponents of the standards envisage? The future will tell.

It is possible that these changes may stem the tide of consortium withdrawals and generate new interest in the assessments from states that have already withdrawn. As Louisiana superintendent John White has noted, “[S]tates … want [test] results that are comparable with other states, they want the cost savings that come with sharing development of test questions across multiple states, but at the same time they want to maintain control of their own test.” Given more flexibility to determine the content, length, and administration of assessments, states could still achieve some of the benefits of collaboration while preserving the ability to respond to local needs and priorities.

The consortia may also emerge stronger as a result of surviving the conflict that has surrounded them. The diversity and number of states taking part in each consortium was always a challenge. As Bill Porter, leader of the High Quality Assessment Project, noted, “It’s challenging to get 20 states around the table really trying to compromise with each other on what to prioritize and how much money to invest in assessments.” With a smaller number of more like-minded states, the consortia may be able to focus more deliberately on improving implementation.

At the same time, however, the consortia will face new competition from other Common Core–aligned assessments. This year, the College Board (which is headed by Common Core lead author David Coleman) rolled out a new Common Core–aligned version of the SAT for high school students, as did the ACT with the Aspire assessment system, which also offers assessments for grades 3–8. Several states have already opted to use the SAT and ACT in high school for federal accountability purposes, drawn by the idea of using a college entrance test to assess student learning.

Whatever fate awaits the consortia, their work has resulted in new opportunities and imperatives for states to work together on assessment design and implementation. As former Maryland schools superintendent Lillian Lowery noted, one of the chief benefits of the consortia was the “communities of practice they generated and the pooled intellectual capital of the states involved.” And despite the problematic implementation of the new assessments and the political controversy that has swirled around them, evidence suggests that the consortia-designed tests are a substantial improvement over previous state assessments. A significant number of states are now engaged in unprecedented collaboration around common standards and tests—and how to deliver instruction to meet them—and these efforts are likely to live on, with or without the consortia.

Ashley Jochim is a research analyst at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell. Patrick McGuinn is professor of political science and education at Drew University and a senior research specialist at the Consortium for Policy Research in Education.