by Drew DeSilver, Pew Hispanic

Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court decided to take up a Texas case that challenges the way nearly every U.S. voting district – from school boards to Congress – is drawn. The case, in essence, asks the court to specify what the word “person” means in its “one person, one vote” rule. The outcome of the case could have major impacts on Hispanic voting strength and representation from coast to coast.

Ever since a series of landmark rulings in the 1960s, districts have been drawn “as nearly of equal population as is practicable.” (As Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote for the majority in Reynolds v. Sims, “Legislators represent people, not trees or acres. Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities or economic interests.”) The high court didn’t directly say what “equal population” meant, but states and localities have almost invariably used total population figures. And that population is determined by the decennial census.

However, the appellants in the Texas case, Evenwel v. Abbott, argue that districts instead should be drawn to have equal numbers of eligible voters. (The case involves redistricting within states, not reapportioning congressional seats among states.)

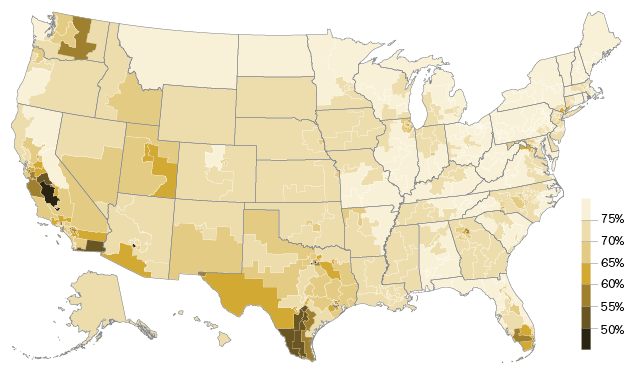

That’s a big distinction, because in many states, districts with nearly equal total populations can have dramatically different numbers of eligible voters (that is, U.S. citizens ages 18 and older). We approximated the disparity using 2013 demographic data for all 435 U.S. House districts from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey: Eligible voters ranged from 81.3% of the population (Florida’s 11th District, located north of the Tampa Bay area) to 42.9% (California’s 40th District, comprising East Los Angeles and adjacent communities). California’s 40th, in fact, has barely half as many voting-age citizens (308,276) as Oregon’s 4th District (597,613, the most of any district).

That’s a big distinction, because in many states, districts with nearly equal total populations can have dramatically different numbers of eligible voters (that is, U.S. citizens ages 18 and older). We approximated the disparity using 2013 demographic data for all 435 U.S. House districts from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey: Eligible voters ranged from 81.3% of the population (Florida’s 11th District, located north of the Tampa Bay area) to 42.9% (California’s 40th District, comprising East Los Angeles and adjacent communities). California’s 40th, in fact, has barely half as many voting-age citizens (308,276) as Oregon’s 4th District (597,613, the most of any district).

As the map (above) and chart (right) might suggest, there’s a strong negative correlation between share of eligible voters and share of Hispanic population. Of the 25 districts with the highest Hispanic population shares, 19 also are among the 25 districts with the lowest eligible-voter share. This is because so many Hispanics aren’t eligible to vote, either because they’re not U.S. citizens or because they’re younger than 18. By our calculations, only about 45% of the nation’s nearly 54 million Hispanics are eligible to vote.

There also are clear partisan differences between districts with high and low shares of eligible voters. Of the 35 districts where less than 60% of the population are voting-age citizens, 29 are held by Democrats; Democrats represent 19 of the lowest-ranking 20. On the other end, Republicans represent 31 of the 42 districts where 77% or more of the population are voting-age citizens, and 16 of the highest 20.

What would happen if the Supreme Court were to rule in favor of the Texas appellants (who, it should be noted, already have lost at the district-court level) is unknown. One possibility is that districts with relatively few eligible voters would be redrawn to include more of them – that could mean bringing more whites and Republicans into what are now largely Hispanic, Democratic-voting districts, or combining such districts to bring up the eligible-voter population. And that, in turn, could affect Hispanic representation in the House, which has risen from five in 1973 to 17 in 1993 and 28 in 2013.

All of this should be taken as illustrative rather than definitive. There are factors beyond age and U.S. citizenship that affect eligibility. Our data do not reflect other aspects, such as residency rules, imprisonment, prior felony convictions and mental incompetency. Americans living overseas may be eligible to vote but aren’t covered by the American Community Survey. (Two political scientists, Samuel Popkin and Michael McDonald, addressed those issues in their influential 2001 paper on turnout rates.)

Most important, while the American Community Survey asks about immigration and U.S. citizenship status, the decennial census does not. And because the decennial census counts everyone (which the ACS, being a sample-based survey, does not), it has been the only source of data for drawing district lines. That means that if the Supreme Court requires districts to be drawn with equal numbers of eligible voters, it may also have to decide just how those eligible-voter numbers are to be determined.