You know that old saw about following the money?

An intriguing spat followed hard on the heels of the U.S. Department of Education’s recent announcement that the Texas Education Agency (TEA) had improperly denied special education services to tens of thousands of students. Gov. Greg Abbott, on whose watch the federal investigation began, launched the first salvo with a letter that seemed to place primary blame on Texas’s school districts.

“The past dereliction of duty on the part of many school districts to serve our students and the failure of TEA to hold districts accountable are worthy of criticism,” Abbott wrote. “Going back to 2004, the letter points to multiple failures by local school districts to adequately address the needs of our most vulnerable students.”

The “local” failures, the letter went on to concede, stemmed from following state policy limiting the number of students whose disabilities would be acknowledged to 8.5 percent of Texas schoolchildren.

School districts fired back quickly, saying they were adhering to the agency’s directives, which appeared to be an attempt to satisfy the legislature’s desire — not expressed in a bill or a law but in a report — that schools drastically cut special ed spending.

Who’s right? A look back at “Denied,” the September 2016 Houston Chronicle investigation that triggered the federal probe, is instructional.

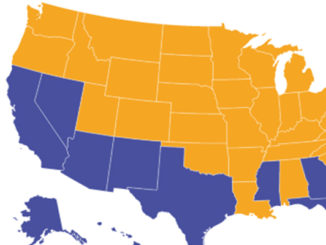

A well-established body of U.S. law says children with disabilities are entitled to a free and appropriate education, but in practice most schools are under continual pressure to provide basic services on a shoestring. While neither Congress nor state legislatures have ever funded that mandate adequately, Texas appears to be the only state that has attempted to bridge the shortfall by establishing a cap on enrollment.

In 2003, Texas lawmakers slashed the TEA budget of some $30 billion a year by $1.1 billion, creating a precarious funding situation that only compounded in the ensuing years. In 2004, the Texas House Public Education Committee issued a report on ways the state could guard against the “overidentification” of students receiving special education services.

Overidentification typically refers to students who are mistakenly referred to special ed for other unmet needs, such as falling behind academically, not learning English quickly, or engaging in behavior perceived as defiant because of racial bias. Reducing overidentification typically means addressing the underlying needs of the student or changing the system.

According to the Chronicle’s series — which won two Education Writers Association awards, among other accolades — four TEA officials subsequently decided that no more than 8.5 percent of students should receive services.

When the policy was created in 2004, 11.6 percent of Texas students received special ed services, a little more than a percentage point below the national average. By 2016, that percentage had dropped to 8.6 percent. The number of students had dropped by a third.

The TEA officials’ explanation of the 2004 decision was that they had not set a cap but rather an “indicator” of school performance. Districts that identified too many students with disabilities were audited. Potential sanctions listed in a compliance manual included fines, regulator visits, “corrective action” plans, and even wholesale state takeover.

In response, the Chronicle found, districts came up with a host of creative mechanisms for turning families away, ranging from saying children were not impaired enough or were too intelligent to qualify, to printing brochures listing options outside the public school system.

Asked about the swift drop in schools’ special ed caseloads, local and state officials sometimes said better teaching methods or early intervention had reduced unmet needs.

In his January 11 letter, Abbott directed the TEA to come up with a plan to remedy the situation within a week: “Throughout your tenure, you have advised me of changes taking place at TEA to strengthen and better support special education in Texas. Through your efforts, much has already been done. However, it is obvious that more can be done, and more must be done.”

During last spring’s legislative session, Abbott, it’s worth noting, refused lawmakers’ pleas to revamp Texas’s broken school funding system which, 15 years after the billion-dollar cut, has left rich and poor districts in dire circumstances. Without buy-in on his priorities — a bill limiting transgender students to the use of the bathroom corresponding to the gender they were assigned at birth, and private school tuition vouchers — Abbott said he would not entertain a funding review.