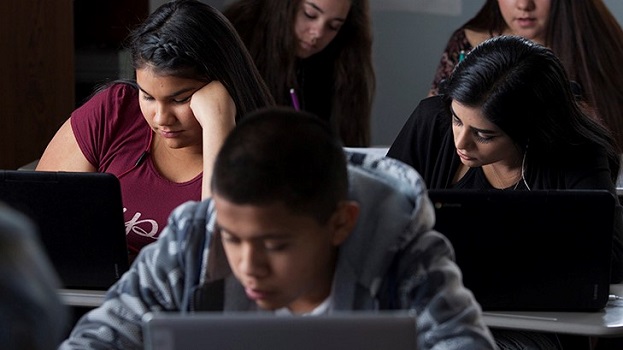

An uptick in immigration raids and deportations has had wide-ranging impacts on America’s schools, its teachers, and its students — immigrant and otherwise, new research has found.

Two-thirds of the 5,400 teachers, principals, and counselors who responded to a survey conducted from late October to mid-January said immigration enforcement had affected their schools, with those in the South hardest hit, and schools with greater percentages of poor and immigrant students feeling it the most, new research from the Civil Rights Project at UCLA found.

Other findings from the survey included:

- 90 percent of administrators said they saw behavioral or emotional problems among immigrant students (defined by the study as children who weren’t born in the U.S. or who have at least one immigrant parent), with 25 percent saying it was a major problem.

- 84 percent of teachers said students expressed concerns about immigration enforcement at school.

- 68 percent of administrators said absenteeism among immigrant students is a problem.

- 70 percent of principals and counselors reported academic decline among immigrant students.

The ripple effects go beyond immigrant students to their peers: two-thirds of teachers nationally said learning for non-immigrant students has been impacted by ICE raids as children expressed concern for classmates whose families had been targeted.

Most respondents worked at Title I schools, those that receive federal aid because they educate large percentages of low-income students. That means “the ones that struggle the most to close achievement gaps are hit the hardest by this enforcement regime,” said Patricia Gándara, one of the study’s authors.

The discussion came two days after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to expedite a case dealing with the DACA program, maintaining Dreamers’ status and effectively removing a looming deadline, though thousands have lost their protected status since the Trump administration announced in September it would end the program on March 5.

Although DACA has been in the news, schools are affected by more wide-ranging immigration concerns, panelists said.

“I want to remind you that even if we were to get a clean DACA bill, as long as these parents are still terrorized by this immigration enforcement regime, the schools will continue to suffer in the same way that we’ve seen them suffering,” Gándara said. “We have got to have something that includes, but goes beyond, DACA.”

A second survey, also from the Civil Rights Project, looked at how teachers are impacted and found that educators are reporting symptoms consistent with secondary traumatic stress — “the emotional duress that results when an individual hears about the firsthand trauma experiences of another,” researchers said.

It also found that 85 percent of teachers reported increased anxiety and stress due to students’ immigration concerns.

National Education Association president Lily Eskelsen García told stories of several teachers who reported issues like increased bullying of immigrant students or staff being asked to step in as foster parents if undocumented parents are deported.

“The calls coming into NEA on immigration issues have never been higher and never been more frightening,” she said.

Many teachers in the survey also reported heavier workloads as they take on other duties, outside their usual roles, like legal advocacy. They spoke of deteriorating trust within school environments as they weren’t sure which colleagues might report students to immigration enforcement or otherwise undermine their safety.

Other researchers discussed the legal underpinnings for so-called sanctuary campuses, or the idea that school leaders place limitations on immigration enforcement on campus, and the status of children who return to Mexico who are American citizens.

Though the common perception is that sanctuary campuses flout federal immigration law, there are actually strong legal underpinnings for the movement, including a 1982 Supreme Court case guaranteeing public K-12 education to all children regardless of immigration status, and constitutional protections against illegal searches, said Julie Sugarman, senior policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute.

There are about 600,000 students in Mexico who are U.S. citizens, according to Bryant Jensen, a professor at Brigham Young University. These students have faced bureaucratic hurdles in re-enrolling in Mexican schools, and when they do, they’re more likely to be in rural schools, which are generally of lower quality, he said. Bryant’s research recommends reviving an education partnership between the U.S. and Mexico, and encouraging similar partnerships at the state and school district levels.

Carolyn Phenicie is an education policy analyst for the 74