A new survey of research into charter school effectiveness has linked so-called no-excuses practices in urban charter schools to sizable academic gains.

Published in the Winter 2018 edition of The Future of Children, a journal jointly published by Princeton University and the Brookings Institution, the survey found that spending three years in one of these schools produces gains equivalent in size to the nationwide achievement gap between black and white students.

“Charter Schools and the Achievement Gap” is notable because it identified similar findings in major studies that used differing methodologies and drew on several kinds of data. It defines no-excuses policies as longer school days and years, use of student assessment data in the classroom, rigorous discipline, and frequent observation of teachers, among other strategies.

Those practices, survey author Sarah Cohodes of Columbia University’s Teacher College asserts, can be transferred successfully to traditional district schools. “I think the question on the ground is, charters are going to continue to exist, so given that, what can be learned from them?” she told The 74. “There is a lot of power in focusing in what has worked.”

Simply asserting that a no-excuses approach is effective is likely to fan the flames of controversy. The phrase was coined to suggest that educators in these schools would not accept rationalizations for the achievement gap — but critics typically depict the schools as rigid places where children face unreasonable disciplinary practices and are constantly drilled in preparation for standardized tests.

Cohodes’s survey takes pains to address criticisms frequently leveled at these schools. For example, to probe whether their academic results can be attributed to attracting families who are particularly motivated, she examined research that looked at schools whose admissions produced cohorts of students who both attended and didn’t win seats.

Though this type of study typically considers schools that are popular enough to require an admissions lottery, Cohodes found similar outcomes in studies by Stanford University’s Center for Research on Educational Outcomes — widely regarded as the gold-standard charter school research — that merely matched charter school students with district school peers having the same individual characteristics, such as English language proficiency, disability, and race.

The CREDO studies consistently found positive gains for low-income children of color in urban charter schools, particularly those that are part of charter management organizations.

Cohodes also noted that similar gains are seen in turnaround schools, in which underperforming traditional schools are taken over by a no-excuses CMO.

“This turnaround method instills charter school management techniques and curricula into traditional public schools. At least initially, the schools serve the same students. Using non-lottery methods, an evaluation of this takeover strategy in Boston and New Orleans found large positive impacts for attending such a turnaround, similar in magnitude to those at no-excuses charter schools,” she wrote.

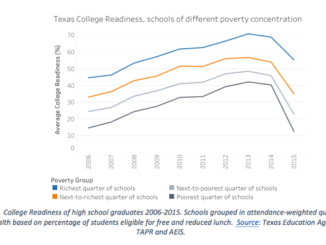

Cohodes looked at markers of success other than standardized test scores, such as college readiness assessments like the ACT, Advanced Placement coursework, and college persistence.

“In Boston and New York, where there are enough historical lottery data to track students for longer periods, such charter schools increase enrollment in four-year colleges and reduce teen pregnancy and incarceration,” the review notes.

The survey builds on Cohodes’s past research. In 2016, she and University of Michigan scholar Susan Dynarski found that urban charter schools in Boston, which have detailed lottery information going back a long time, produce large, positive gains.

“The effects are particularly large for disadvantaged students, English learners, special education students, and children who enter charters with low test scores,” they wrote in a previous Brookings report on the Boston research.

“When I started doing this research, I did not think charter schools were a good thing and that they were siphoning resources from regular public schools,” Cohodes said. “Despite my revelation in ’07 or ’08, I don’t think of myself as a charter advocate. I am pro- whatever works for kids.”

Indeed, in the survey, she argues that replicating successful charters isn’t likely to be the key to closing the nation’s academic achievement gaps, given that only about 5 percent of U.S. students attend charter schools and a smaller number the no-excuses programs.

A decade of rigorous research is consistent, Cohodes said: On the whole, charter schools perform no better or worse than their district counterparts – with the exception of schools using the urban no-excuses model, many of which belong to networks such as KIPP that have had success replicating the strategies in numerous communities.

“It’s not just the charter label,” Cohodes said. “If you want to expand charter schools or replicate charter schools, you have to look at what makes them successful.”

In fact, the paper notes that a small experiment conducted in Houston showed that no-excuses strategies can be implemented in district schools, though there are hurdles.

“I think the challenge is, you have to do it a whole building at a time,” Cohodes said. “Organizations are really hard to change.”

James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center, didn’t disagree but is more skeptical that no-excuses practices will become widespread in district schools.

“It would be nice to have more study of what is and isn’t transferable,” he said. “There are obviously political questions. But if all of the politics disappeared and all of the superintendents and all of the school boards across the country decided to adopt these strategies, the overarching challenge remains the finding of talent.”

Implementing just one or a few isn’t likely to create change. “It’s a constellation of practices done well together,” he said. “They all build on each other. It really is getting a bunch of things right, which is why replication is so hard.

“It’s just damn hard work.”

Beth Hawkins is a senior writer and national correspondent at The 74.