The Economist

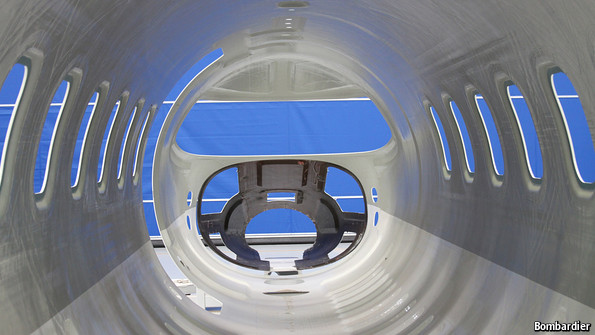

PASS through the gates of the Bombardier plant in Querétaro and you leave the Mexico of potholed roads and blaring horns behind: welcome to a strangely serene place called North America.

In the car park neat lines of vehicles all face the same way—almost unthinkable elsewhere in Mexico. The factory is run by a woman—ditto. Enter the building where the cockpit, fuselage and tail section of Bombardier’s new eight-seat Learjet 85 business jet are being made and it looks more like a laboratory than a factory.

Technicians with face masks work behind glass in a dust-free room. Instead of metal, layers of carbon fibre cut by laser are moulded and baked in a giant oven to make a seamless fuselage (pictured). There are no pungent, oily smells, no urgent, whining drills, no soul-stirring hammering. It would be the dullest factory visit your correspondent has ever made—were it not for what it says about the future of North America.

With the exception of the wings, which are made in Northern Ireland, the Learjet 85 is a North American story. Bombardier, a Canadian firm based in Montreal, took over Learjet, an American firm, in 1990. When the Mexico-made carcass reaches Learjet’s headquarters in Wichita, Kansas, for kitting out, it is married to engines built in Canada, but designed by America’s Pratt & Whitney. It is fitting that the 85’s maiden flight will, all things being equal, come within a few weeks of the 20th anniversary of the North American Free-Trade Agreement coming into force on January 1st 1994. Without NAFTA, a trinational endeavour like the new Learjet would be unthinkable.

Three into one

The new aircraft represents a $250m bet by Bombardier that Mexico could provide not just routine labour but manufacturing that depended on high-tech materials. It placed the bet, according to Michael McAdoo, head of global strategy, because it was seeing old European rivals go bust and new ones emerging in low-cost countries such as China and India. Workers in Wichita and Montreal complained. But Mr McAdoo says they came to realise that if outsourcing some manufacturing to Mexico ensured Bombardier’s future, it would safeguard their own jobs for years to come.

A shared concern with employment is one of the reasons that politicians are starting to pay more attention to NAFTA, which in recent years has been failing to live up to its early promise. Rebooting the agreement tops the agenda at the meeting of the leaders of the three countries scheduled to take place in Mexico this February. “There’s a joint willingness among all three countries to relaunch the idea of North America, not just in terms of manufacturing, but in innovation and design,” says Sergio Alcocer, under-secretary for North America in Mexico’s foreign ministry.

In May 2013 Barack Obama—who in 2007, on the campaign trail, called NAFTA a “mistake”—trumpeted cross-border trade on a visit to Mexico, noting that the United States exports more to Mexico than to the BRIC countries—Brazil, Russia, India and China—combined. On a visit in September his vice-president, Joe Biden, dwelt on NAFTA’s untapped potential. The trade agreement was beginning to look out of date. There needed to be freer movement of “goods, people and information” across the borders, despite security worries. More shared infrastructure investment was necessary. Obliquely, he acknowledged that politicians had held up such improvements: “Make us do it,” he urged businesspeople and the public.

In the United States, the potential of closer integration has been outweighed—at least in the eyes of politicians—by the fear of job losses, as well as illegal drugs, crime and immigration from Mexico. Canada, Bombardier’s success notwithstanding, long ago started seeing Mexico as a rival in its relationship with the United States, rather than a partner. Mexico, in which almost half of the population lives in poverty, much the same level as 20 years ago, has mixed feelings.

Robert Pastor, head of the Centre for North American Studies at American University in Washington, DC (and one of NAFTA’s most prominent advocates) says the bloc has become a piñata—something politicians and pundits alike enjoy bashing. Yet a poll Mr Pastor recently commissioned showed that the people of the United States still much prefer the idea of free trade with Canada and Mexico than with the European Union, China or India. And though support in the United States has dwindled in the past ten years, in Canada and Mexico it is on the rise.

The case for optimism about NAFTA is not limited to opinion polls and political summitry. Nor is it simply a response to the doldrums that the agreement has been in over most of the past decade, with its infrastructure badly in need of an upgrade and regulatory structures left behind by the pace of technological change. The fundamentals also favour a resurgence in North American trade. Mr Alcocer talks of a “rejuvenated” region benefiting from cheap and abundant energy, a young workforce, and costs that are increasingly competitive with those in China. The aim, though quietly stated, is to develop a “Factory North America” to rival “Factory Asia”.

Bumpy ride

Part of NAFTA’s problem is that its original take-off was accompanied by a level of hyperbole its subsequent flight path could never match. Its chief architect, President Carlos Salinas of Mexico—who signed the treaty with George Bush and Canada’s prime minister, Brian Mulroney, in 1992—hoped it would make Mexico a first-world country. In 1993 Vice-President Al Gore compared it to the creation of NATO and the Louisiana Purchase.

And for its first six years the pact’s success was remarkable. Cross-border investment ballooned. Rapid growth led to the three countries’ share of global production hitting a peak of 36% in 2001. But the progress stalled (see chart 1). Fears of terrorism in the United States after September 11th 2001 led to a security clampdown on its borders that still hampers trade today (the drug war in Mexico has not helped). Even more destabilising, after China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, American firms in Mexico upped sticks and headed across the Pacific. Trade within North America eventually started to grow again; but global trade—principally with China—mushroomed (see chart 2). By 2011, North American production had fallen back to 26% of the global total, similar to the shares in Asia and Europe.

And for its first six years the pact’s success was remarkable. Cross-border investment ballooned. Rapid growth led to the three countries’ share of global production hitting a peak of 36% in 2001. But the progress stalled (see chart 1). Fears of terrorism in the United States after September 11th 2001 led to a security clampdown on its borders that still hampers trade today (the drug war in Mexico has not helped). Even more destabilising, after China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, American firms in Mexico upped sticks and headed across the Pacific. Trade within North America eventually started to grow again; but global trade—principally with China—mushroomed (see chart 2). By 2011, North American production had fallen back to 26% of the global total, similar to the shares in Asia and Europe.

In a 2013 overview of NAFTA’s effects, the Congressional Research Service, an American government think-tank, portrayed it as something of a damp squib: “In reality, NAFTA did not cause the huge job losses feared by the critics or the large economic gains predicted by supporters.” In a 2009 study, Robert Blecker of American University and Gerardo Esquivel of the Colegio de México found that for all its promise NAFTA had failed to close the development gap between Mexico and the United States. “During the first seven years…North America showed signs of becoming a more integrated and competitive regional market area, but much of the progress on the regional front was reversed in the next eight years.”

The sense of something stymied, and the need for smoother borders and better infrastructure, become apparent the moment the Learjet 85’s fuselage is loaded on to a lorry and sets off up Mexico’s juddery Highway 57 towards the border at Nuevo Laredo. Before it gets there, its driver and cab will be replaced by a drayage team that hauls the cargo to just over the other side of the border. There an American driver and cab will take it to Wichita.

This three-stage irksomeness mostly stems from a violation of NAFTA on the part of the United States, which waited 17 years after the agreement had come into force before honouring a pledge to allow Mexican truckers to cross the border and deliver goods to their final destination. When it did so it was in the form of a three-year pilot programme up for renewal in 2014. As yet, few Mexican truck companies have signed up for the rigorous checks involved, in case the programme lapses.

At the border, those drayage firms face excruciating waits. On one recent afternoon the tailback stretched 8km (5 miles) without even a Coca-Cola machine by the road for the thirsty drivers. Large X-ray devices are meant to allow cargo to flow faster through United States customs, but spot checks mean the wait usually takes several hours. In 2009, based on an estimate that 1.5m lorries crossed from Nuevo Laredo each year, the Tijuana-based Colegio de la Frontera Norte reckoned the annual cost of delays added up to almost a third of a billion dollars.

Youth and energy

It is a similarly depressing story at the nearby railway bridge. The snakelike trains loaded with cars, scrap metal and grain—mostly built by Bombardier, and operated by Kansas City Southern, a United States-owned company—do not change locomotives at the border. But halfway across the bridge a team from the destination climbs up into the cab, and the departing crew trudges back home.

American University’s Mr Pastor puts much of the blame for such inefficiencies on the United States’ security fears, and the allocation of resources that goes along with them. Since 2001, he says, $186 billion has been spent on border security. In the last fiscal year $18 billion was spent on immigration enforcement. Only a tiny fraction of that has been spent on upgrading border infrastructure to make trade flow more freely.

However inconvenient the hours of waiting at the border can be, though, the time lost is little compared with the weeks spent shipping goods from China. Ten years ago those weeks were a price worth paying for cheaper manufactures. Now the differential has been reduced, perhaps even reversed. The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) calculates that if Mexico’s higher manufacturing productivity is taken into account, by 2012 the cost of labour in China was no less than in Mexico. By 2015 BCG expects Mexico to have a cost advantage of almost 30%.

Mexico’s free-trade agreements with 44 countries—most of them entered into since NAFTA was set up—add to the attraction of expanding supply chains in the region. So, from the perspective of the United States, does the proportion of American content in Mexican and Canadian exports. BCG reckons 37% of Mexico’s exports include parts imported from the United States. That is four times as much as in Chinese exports. One reason is that NAFTA protects the intellectual-property arrangements such close-knit processes require to a degree that is very hard to guarantee when dealing with China; it has enforceable commitments on copyright, patents, trademarks and trade secrets.

As Mexico becomes more attractive, it is seeing industries start to cluster. Mexico is the world’s largest exporter of cars after Germany, South Korea and Japan. Its production of cars recently overtook Canada’s; and German and Japanese carmakers are investing heavily there. Carlos Ghosn, boss of Nissan, which in November opened a $2 billion new plant in Mexico, says it will soon become a bigger export hub than Nissan’s home base, Japan. What Brookings, a Washington think-tank, calls “advanced manufacturing industries”, including aerospace, computers and pharmaceuticals, are all spreading their supply chains across North America—as Bombardier shows. Brookings’ Joseph Parilla says the most high-tech industries will probably remain in the United States for a while—but even advanced technologies like 3D printing will have a role in Mexico.

In the longer term, two further things favour North America; demography and energy. Two-fifths of Mexicans are under 20. Between 2000 and 2030, BCG expects Mexico’s labour force to grow by 58% and the United States’ by 18%, as China’s shrinks by 3%. And Mr Alcocer says the shale-gas revolution, the development of Canada’s oil sands, and a constitutional change in December allowing private firms to invest in Mexican energy, could give the industries employing those people secure supplies of low-cost energy for the foreseeable future.

John Rice, head of global operations at GE, a conglomerate, chairs a business task-force looking at ways of boosting trade between the United States and Mexico. He bubbles over with praise for President Enrique Peña Nieto’s energy reform. “I visit 40 to 50 countries a year…and I don’t see enough countries where leaders are willing to take [such] tough, aggressive, bold actions.” He says Mexican energy is one of GE’s top strategic priorities: “When we think about Mexico we think about energy.”

But linking up energy markets and aligning regulatory standards on everything from green technologies to smart grids will not be easy, and risks stirring up anti-NAFTA forces that have recently been in abeyance. In all three countries, energy arouses prickly notions of sovereignty.

Officials say the White House’s failure so far to approve the Keystone XL Pipeline from Alberta to Nebraska, which would help carry crude from Canada to United States refineries on the Gulf coast, has dampened the faith of prime minister Stephen Harper in deeper North American integration: Canada is looking across the Pacific for oil markets. Many Mexicans remain fiercely nationalistic about their oil. Some fear that its energy reform will allow American firms to shift shale-gas production south of the border before environmentalists clamp down on it at home.

Perhaps the biggest question-mark is whether cheaper energy in the United States will make it so competitive it feels it does not need closer North American ties. If states where wages were hard hit during the housing crisis, such as Nevada and New Mexico, are able to lure businesses directly back from China thanks in part to low energy costs—which they are keen to do—Mexico could be sidelined.

Both and, not either or

That tendency to want to go it alone may be reflected in Washington’s instincts to keep its NAFTA partners at arm’s length in other free-trade negotiations. The Obama administration started talks on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with countries around the Pacific Rim before Canada and Mexico joined. It has chosen so far to rebuff Canada’s and Mexico’s desire to join it on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the European Union, despite the fact that both its NAFTA partners already have free-trade deals with the EU and harmonising all three might make sense. The United States’ “hub-and-spoke” approach to free trade raises resentment to the north and the south.

But in principle the region’s growing links with Asia and Europe are to be encouraged. The alternative, building a Fortress North America in which the three countries try to boost their mutual competitiveness at the expense of the rest of the world, should be avoided. Jaime Serra, a former Mexican trade minister who led the country’s NAFTA negotiators, argues that TPP and TTIP could undermine Mexico’s trade advantages within North America, especially because they would allow other countries low-tariff access to the United States. But if they live up to their billing, helping to promote regulatory harmony and trade in services, which have lagged badly under NAFTA, and if they include businesses that were scarcely around in 1994—mobile phones, e-commerce—the whole region may be better off.

A more seamless North America should help reduce the differences between living standards around the region, which would benefit all three countries—not least because a richer Mexico would mean fewer problems of illegal immigration, violence and corruption in the neighbourhood. Bombardier is an example of progress. Just eight years ago, its site next to Querétaro contained nothing but cacti. Now twice-weekly flights shuttle engineers and technicians between Querétaro, Wichita and Montreal. In the process they pick up bits of the nations’ different languages and cultures, making North America a tangible entity. To them at least, the relaunch of NAFTA, like the launch of the Learjet 85, would be something to celebrate.