By Jorge G. Castañeda

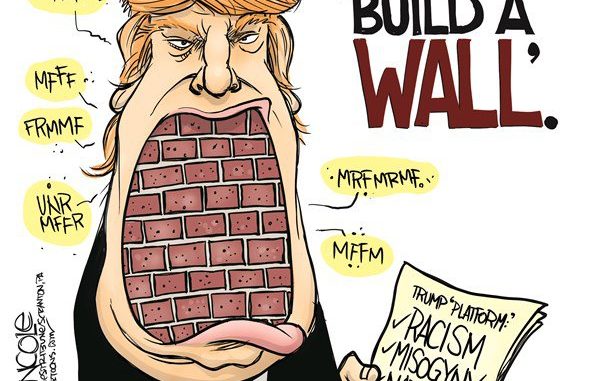

It has been just over a week since President Trump took office, and he already has a diplomatic mini-crisis on his hands. First, he demanded that Mexico pay for his wall along our mutual border — on the very day when Mexican diplomats were to meet with White House officials. When President Enrique Peña Nieto of Mexico rejected that idea out of hand, Mr. Trump tweeted that he should consider calling off a planned visit to Washington next Tuesday. Which is just what Mr. Peña Nieto did.

For Mexico, the cancellation, and the rise in tensions with the United States, are a sad and serious affair.

Sad, because no Mexican wants a breakdown in bilateral ties. Five successive presidents have pursued a new course with our northern neighbor, putting behind us the apprehensions and resentment of the past. The North American Free Trade Agreement, American support during the mid-’90s financial crisis, immigration negotiations in 2001, expanded drug enforcement and security cooperation, and the encouragement of a new mind-set for Mexicans where being neighbors is no longer seen as a problem but as an opportunity: All of this is being questioned and jeopardized.

And serious, because in tying itself to the United States, Mexico has placed all its eggs in one basket: North America, free trade, democracy and respect for human rights. President Trump’s executive orders and his views on these fundamental issues make that decision seem like a mistake.

This is why Mexico today faces a tough choice, given the asymmetry between both countries: accommodate Mr. Trump and get the least-bad deal possible, or lay out a series of red lines or list of American demands Mexico cannot accept and adopt a policy of forceful resistance. It could then attempt to wait Mr. Trump out, hoping that he will open too many fronts simultaneously, that domestic opposition to his excesses will grow, and that Mexico’s allies in the United States and abroad will eventually rebalance the unequal correlation of forces.

Mr. Peña Nieto had no choice but to cancel his trip. But he had partly boxed himself into a corner because of previous indecision or procrastination.

He knew some time ago that Mr. Trump would insist on renegotiation. He knew that several roads could lead to a favorable outcome for all three member countries, but that there could also be dire consequences for Mexico if the road chosen led to a revised Nafta requiring drawn-out deliberations in the legislative bodies of Canada, the United States and Mexico. The agreement would then fall hostage to partisan bickering, with no guarantees of approval. The uncertainty that would entail might easily place new foreign investment in Mexico on hold.

Mexico should have a red line on trade. Everything that can be done without new legislative approval in all the three countries is fair game, but nothing else. Better to have the United States invoke Nafta’s Article 2205, which says that a country can withdraw from the agreement six months after giving notice.

A similar red line should have been drawn by Mr. Peña Nieto on the prickliest, if not the most substantive issue: the wall. Again, incomprehensibly, Mr. Peña Nieto painted himself into a corner by stressing the wall’s payment, rather than its very existence. The crux of the matter should never have been who would pay for it, but rather that it was an unfriendly act toward a friendly country, sending a disastrous symbolic message to Latin America. The real issue is that it will generate countless social, cultural and environmental problems along the border; raise the cost and danger of unauthorized crossings; and attract even more organized crime.

Mexico should now clearly draw another red line. If the United States wants to build a wall, we will use every tool available to delay it and make it more expensive. But we will also point out that President Trump’s wall better be a very effective one. Because it will have to deter, without any further Mexican cooperation, drugs, migrants, terrorists and “bad hombres” from entering. If Mr. Trump “breaks” the border arrangement that our two countries have enjoyed for nearly a century, he “owns” it (the Pottery Barn rule).

Finally, on deportations, Mexico must also publicize its nonnegotiable bottom line. More money and agents for immigration enforcement, punishing sanctuary cities and attempting to send so-called criminals to Mexico is likewise an unfriendly act. Especially when one recalls that the same policy toward El Salvador in the late 1990s made it the most violent country in the world.

Mexico must say clearly that we will encourage all our potential deportees to demand a hearing upon arrest and to refuse voluntary removal; that we will provide legal support, on our dime, for all arrested undocumented Mexicans; and that we will deny entry to anyone whom American authorities cannot prove is a Mexican citizen. These are not simple decisions and are not exempt from the risk of retaliation. But neither is a 20 percent tariff on imports from Mexico, a proposal the White House suggested on Thursday it might embrace.

Mexico’s most effective leverage in this unfortunate and needless conflict lies in its stability on the United States’s southern flank. Washington should count its blessings. For a century, the United States has been an accomplice to Mexican corruption, human rights violations and authoritarian rule. But it has also supported Mexico economically, abstained from seeking regime change, tolerated mass migration from the south and generally treated Mexico with respect. The quid pro quo was immensely and mutually beneficial. Messing with it is worse than rash: It is reckless, for both countries.

Jorge G. Castañeda, Mexico’s foreign minister from 2000 to 2003, is a professor at New York University.