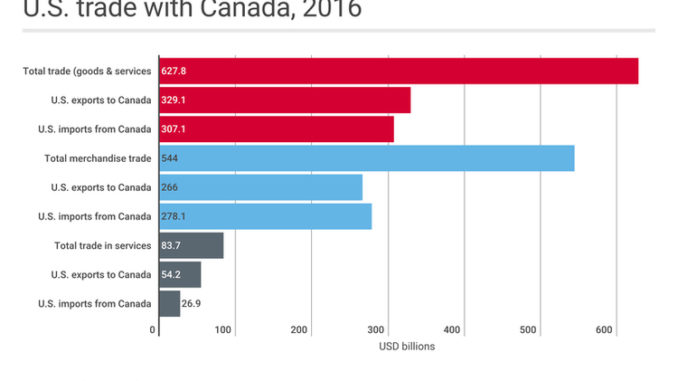

In fact, when goods and services are taken into account, the U.S. has an overall trade surplus with Canada. Moreover, by importing Canadian crude that the U.S. refines and markets worldwide, the U.S. enjoys jobs, economic activity, and exports that it otherwise would not.

Last year, the value of Canadian crude oil exported to the U.S. was roughly C$51 billion. That works out to 67 percent of the value of Canada’s total merchandise trade surplus with the U.S. of about C$76 billion — and 41 percent of U.S. crude oil imports in 2016.

The U.S. refines crude oil — including the imports from Canada — both for its own consumption and for export. And this is where things get interesting.

Since 2011, the U.S. has exported more refined products than it imports. In 2016, of all the countries in the world, the U.S. exported the highest value of refined oil, earning more than US$64 billion. Using the average Canada-U.S. exchange rate in 2016, this converts to nearly C$85 billion — C$9 billion more than the value of Canada’s merchandise trade surplus over the U.S. A significant portion of that crude oil the U.S. refined into products to export — and make money off of — were sourced from Canada.

Moreover, because Canada is a landlocked market with infrastructure that only allows for the export of crude oil to the U.S., the U.S. does not have to compete with any other customers for heavy oil from Canada. So the U.S. doesn’t have to offer a higher price to ensure it receives the supply it requires — on the contrary, the U.S. gets Canadian oil at a discount.

Canadian heavy oil is perfectly suited for the refineries in the U.S. Gulf Coast, which is the largest motor gasoline producing region in the U.S., producing 90 percent of American gasoline exports. Mexico buys over half of all U.S. gasoline exports, and Canada ties Guatemala as the second major destination.

In the last two years, for the first time, the value of U.S. energy exports to Mexico (mainly petroleum products) has been greater than the value of energy imports from Mexico (mostly crude oil). Last year alone, the value of U.S. energy exports to Mexico ($20 billion) was more than double the value of its energy imports from Mexico ($8.7 billion). Mexico’s demand for U.S. gasoline is expected to increase as its gas consumption is rising while its refineries can’t keep up with demand.

The conditions precipitating this change — lower volumes and value of crude oil from Mexico, and increasing demand from Mexico for refined products from the U.S. as prices are rising — may not be the new normal. But, while these conditions do exist, the U.S. pocketbook is benefiting.

The fact is NAFTA eliminated tariffs on crude oil, gasoline, and other refined products, enabling greater and more flexible trade in energy products between the three partner countries. The example of crude oil alone shows how the U.S. makes money by buying a product from its NAFTA partners, processing it, and selling the finished product at a higher price. NAFTA created a web of supply chains in the trade of countless goods and services that benefit all three partners. We shouldn’t take it for granted that we can pull out one thread without unraveling the whole thing.

Naomi Christensen is Senior Policy Analyst at the Canada West Foundation and Mathew Rooney is Director of Economic Growth at the George W. Bush Institute.