by Perry Bacon Jr. and Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux, FiveThirtyEight

The Rev. Billy Graham, the pastor and evangelical leader who died last week and is being laid to rest in Charlotte on Friday, built relationships across party lines, illustrated by the praise Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush,Barack Obama and Donald Trump delivered after his death. But it likely will be hard for an evangelical Christian figure in this era to get the kind of bipartisan acclaim that Graham received in life and in death.

America’s community of self-described evangelicals, about a fourth of the population, is increasingly divided between a more conservative, Trump-aligned bloc deeply worried about losing the so-called culture wars; and a bloc that is more liberal on issues like immigration, conscious of the need to appeal to nonwhite Christians and wary of the president. The split in evangelical Christianity isn’t new, but it appears to be widening under Trump.

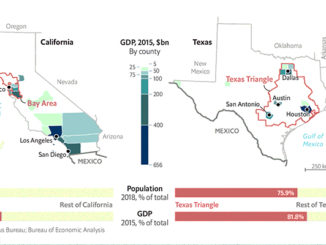

Two factors appear to be driving this divide. First, the number of white evangelicals is in decline in America at the same time that the evangelical population is becoming more racially diverse. According to 2016 data from the Public Religion Research Institute, about 64 percent of evangelicals are non-Hispanic white, compared to about 68 percent in 2006.1

The downward trajectory of non-Hispanic white evangelicals over the past decade might seem relatively small, but that racial and ethnic change also has an important age dimension. Growth in the evangelical community is mostly being fueled by Latinos, one of the nation’s fastest-growing ethnic groups. PRRI’s data shows that while white evangelicals tend to be older, fully half of evangelicals under the age of 30 are nonwhite, and 18 percent are Latino. In other words, change in the composition of evangelicals is only likely to accelerate — and the religious group’s future looks much more nonwhite.

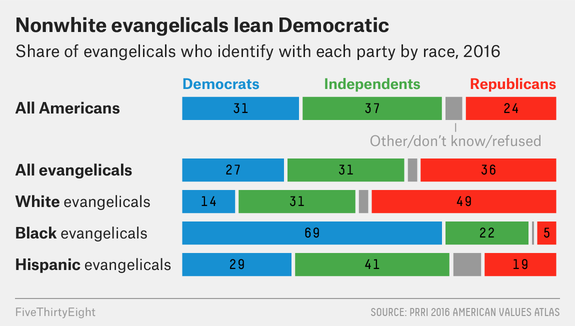

And these nonwhite evangelicals see politics differently than white evangelicals. While the largest plurality of white evangelicals identify as Republicans, most black evangelicals are Democrats. A plurality of evangelical Latinos, in contrast, identify as political independents — and they’re less supportive of the Democratic Party than Latinos overall — but they are still more likely to consider themselves Democrats than Republicans.

The second factor driving this divide among evangelicals is Trump himself. His governing style is, in effect, forcing evangelical leaders to choose between embracing the white evangelicals who overwhelmingly support the president or distancing themselves from the president — and even politics generally — as part of an appeal to their diversifying congregations.

The white conservative camp

Non-Hispanic white evangelicals are conservative on a broad range of issues. They overwhelmingly backed the presidential campaigns of John McCain, who had at times criticized leaders of the “Religious Right,” and also Mitt Romney, despite some evangelicals’ discomfort with Mormonism.

That overwhelming support for Republican candidates was evident in Trump’s election as well, as the GOP nominee won about 80 percent of the white evangelical vote in 2016 even though he’d been through two divorces, was accused of sexual assault and struggled to speak about the Bible coherently.

Now in office, conservative Christian leaders are strongly backing the president, even at times when almost no one else will. Jerry Falwell Jr., the president of evangelical Liberty University, defended Trump’s controversial comments in the wake of the violent white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Amid allegations that Trump had an extramarital affair, Franklin Graham, Billy Graham’s son and head of the non-profit Samaritan’s Purse, downplayed the controversy.

In a recent New York Times op-ed, David Brody of the Christian Broadcasting Network cast Trump as God’s gift to evangelical Christians, arguing, “The Bible is replete with examples of flawed individuals being used to accomplish God’s will.” Congressional Republicans often defend the president, but few compare him to biblical figures.

Why are influential figures in the white evangelical community so willing to align themselves with Trump? Well, first of all, Trump remains popular with white evangelical voters. A Pew survey from December found that 61 percent of white evangelicals approved of Trump’s job performance,2 compared to 32 percent of voters overall. (This was a substantial decline from Trump’s 78 percent approval among white evangelicals in February 2017, but they are are still one of the most pro-Trump blocs in the electorate.)

Secondly, on policy issues that some white evangelical leaders and activists care passionately about, Trump has delivered. He has embraced the GOP effort to block any federal dollars from going to Planned Parenthood, signed into law a provision that makes it easier for states to keep their funds from being used at Planned Parenthood clinics, reversed an Obama administration policy that directed schools to allow transgender students to use the restroom of whichever gender they identify with and backed a push to allow ministers to formally endorse candidates without the risk of losing their tax-exempt status.

“Conservative evangelicals will acknowledge that Trump has problems, but he’s moving forward policy on the issues they care about, and in a sense that’s all that matters for them,” said Richard Flory, a University of Southern California sociologist focusing on religion. “Trump is helping with conservative evangelicals’ broader goal of keeping America an essentially Christian nation, with the moral values that white Christians support.”

Broadly, Trump and his administration have aligned with conservative Christians who argue that their traditional values on issues like gay rights are ignored in an increasingly liberal culture. “George W. Bush was the evangelical candidate in 2000: He pushed traditional conservative policies, but he doesn’t come close to Mr. Trump’s courageous blunt strokes in defense of evangelicals,” wrote Brody. Trump “easily wins the unofficial label of ‘most evangelical-friendly United States president ever.’”

The diverse non-Republican camp

Brody may have an argument — but only if you limit your definition of evangelicals to the traditionally Republican, mostly non-Hispanic white camp. Since Trump has been in office, many prominent evangelical leaders, white and nonwhite, have criticized his cutbacks in the number of refugees allowed to enter the U.S., the president’s allegedderogatorycomments about immigrants from “shithole countries” and his decision to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which protected “Dreamers,” or undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children, from deportation.

During the 2016 campaign, many high-profile evangelical pastors kept theirdistance from the candidate. In one case, it was reported during the campaign that Joel Osteen, who runs a megachurch in the Houston area with nationally broadcast services, was endorsing Trump. In response, the pastor put out a statement declaring that was not true, adhering to his pattern of keeping a low-profile on political issues.

It’s not that differences among evangelical leaders didn’t exist before, but they seem more evident with Trump in the White House. And the demographic changes only exacerbate them. On immigration policy in particular — an issue that Falwell and Franklin Graham have not publicly disputed Trump on — the sizable nonwhite segment of the evangelical community has obvious implications.

“Evangelicals are very concerned about this, especially because so many evangelical congregations have Dreamers as part of our churches,” Russell Moore, a leader in the Southern Baptist Convention, told USA Today recently in explaining why he and other evangelicals were pressing Trump to resolve the DACA issue.

Churches where no single racial group dominates remain relatively rare, especially among evangelicals, but “we’re increasingly seeing diversity within predominantly white churches, and that’s likely to have a big effect on the way pastors approach issues around race or immigration,” Chaves said.

Larger churches are also likelier to be more racially diverse, which could help explain why megachurch pastors like Osteen and California’s Rick Warren have been more reluctant to get involved with politics in general — any stance on a political issue could upset a significant portion of their congregants. (The website of Osteen’s church describes itself as “known throughout the world as a model for racial harmony and diversity,” and that it “has become a congregation of nearly equal numbers of Caucasian, Hispanic and African-American members.”)

For leaders who are focused on evangelism — that is, bringing more people to evangelical Christianity and keeping them engaged — embracing Trump and his controversial stances on immigration could actually be something of a liability. In contrast, several of Trump’s strongest defenders in the evangelical community, like Falwell and Graham, don’t run actual churches.

This tension between inclusivity and political cohesiveness isn’t new for evangelicals. Billy Graham famously struggled — and many have argued, failed — to find a balance on race in the civil rights era. He integrated his Southern crusades, or revivals, at a time when integrated revivals were extremely rare, but he was unwilling to speak out forcefully against racism.

But today, non-Hispanic white evangelicals are shrinking in numbers while remaining politically powerful, which presents a unique conundrum for evangelical leaders. Some, like the traditionalist Franklin Graham, are linking themselves closely to a controversial president, and in their view that alliance helps advance pro-evangelical politics. At least some other leaders, however, appear to have made the calculation that they’ll risk giving up some access to the halls of power in favor of a more inclusive message.

Perry Bacon Jr. is a senior writer for FiveThirtyEight. @perrybaconjr

Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux is a writer and reporter living in Chicago. @ameliatd