Usually, we claim to have little use for people who are all talk. We mock second-guessers and those Monday-morning quarterbacks who tell others what they should have done. Like most people I know, I’ve always been most impressed by those who do things. Build things. Repair things. Whether we’re talking about fixing a car or teaching algebra, what matters is taking responsibility for a task and then doing it well.

Yet I fear that education reform is more and more the province of talkers and second-guessers. My example-of-the-moment is the bizarre fascination with the documents states drafted to comply with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). These exercises in industrial blather have been treated like the Dead Sea Scrolls by Beltway talkers and second-guessers, who’ve made a cottage industry of pocketing foundation cash in order to rate the plans. What I find striking is that—rather than giggling bemusedly at this charade—reporters, advocates, and even public officials are treating it with remarkable seriousness.

We wind up with state bureaucrats (far removed from the actual work of schools and systems) dreaming up paper schemes that are then critiqued by Beltway impresarios (who are even further removed)—and worrying about whether they’ll get nice notices on their federally-mandated paperwork. Happily, the musings of the professional talkers are no longer enshrined in federal law, but it’s clear they still matter.

Bizarrely, the whole exercise proceeds as if there were some agreed-upon “one best” approach to educational accountability. Of course, there’s not. In fact, the actual authorities on accountability—you know, the folks who spend lots of time examining how accountability works in practice—usually take pains to note that the “right” approach to accountability will vary with culture, context, and experience.

Of course, such niceties tend to get lost amidst the solemn pronouncements, with unfortunate results. Nowhere is that more evident than in the push for states to set “ambitious” goals for student performance. As Brendan Bell and I noted the other week in U.S. News, “It turns out that the easiest thing in the world is for public officials to set ‘ambitious’ made-up targets for someone else to meet.”

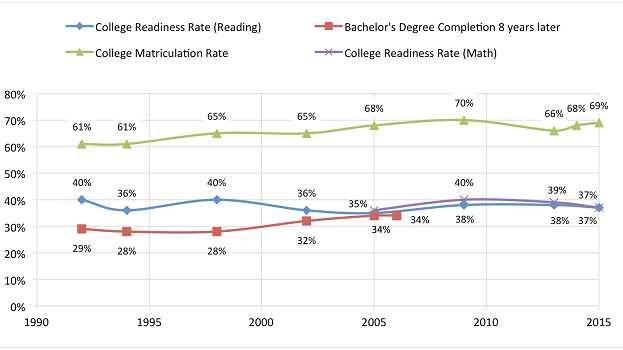

For example, as Brendan and I noted, Oregon‘s plan promises that 80 percent of students will demonstrate “postsecondary readiness” by 2025-25, up from 54 percent in reading and 43 percent in math in 2015-16. To put this in context, between 2003 and 2015, the share of Oregon fourth graders proficient in reading rose by 3 percentage points, with a 4 percentage-point increase in math. This means Oregon’s targets would require roughly 10 times as large of gains as what students posted in the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) era—in just over half the time.

Kansas promises that 75 percent of students will be proficient in reading and math by 2029-30. Just last year, 42 percent scored proficient in reading, and only 33 percent did so in math. The share of fourth graders proficient on NAEP reading increased 2 percentage points between 2003 and 2015, while the percentage proficient in math held constant. So, Kansas’ ESSA plan requires that reading scores increase more than 16 times faster than they did during the NCLB era . . . and its math scores infinitely faster than that.

The District of Columbia plan expects that 85 percent of all students will meet or exceed expectations on the PARCC exam by 2038-39. In 2016, just 27 percent of students in reading and 25 percent of students in math did this well. (Any guesses as to how many of those who crafted this plan expect to be around in 2038 to take responsibility for whether they met their goal?)

You get the idea. The peculiar thing is that this kind of “ambition” gets celebrated—with the architects cheered on for their boldness and courage, rather than ridiculed for operating like drunken Soviet central planners.

As Brendan and I put it:

Those who dreamed up each state’s new goals know they won’t be held responsible for meeting them. Even those nominally on the hook, like state superintendents, take refuge in the knowledge that they are seen as symbolic figures who don’t actually run schools. Meanwhile, the actual responsibility for meeting these goals will fall upon the educators and leaders in local school systems. And when these individuals point out where the fabulists have gotten silly, they’ll be denounced as whiners.

When silly goals predictably encourage corner-cutting, compliance-fueled overtesting, and even outright cheating, the officials in charge (and the Beltway impresarios) are predictably “shocked! SHOCKED!” They aren’t held accountable for the wrongdoing and have a field day denouncing it—and promising to do something about it.

In well-run organizations, boards and executives who have skin in the game are the ones setting accountability targets. This tends to keep targets grounded, real, and useful. But this is not how most states have approached their ESSA goals. Look, accountability is a good thing, especially when it means asking professionals to be responsible for doing their job and doing it well. But when it involves public officials worrying about the opinion of armchair quarterbacks, that’s not accountability. It’s an exercise in unaccountable play-acting.

I fear that this is the consequence of ceding the spotlight to talkers—and those who talk about talkers. It reifies self-assured sloganeering at the expense of practical complexities. It slights those who actually do the work. And I suspect that it’s pulling us further away from responsible accountability systems and public leadership.

Frederick Hess is director of education policy studies at AEI and an executive editor at Education Next.