The numbers suggest Hispanics are making astonishing gains in college attainment. From 2001 to 2011, the number of Hispanics with at least a bachelor’s degree nearly doubled from 2.1 million to 3.8 million, and overall attainment rose from 11 percent to 14 percent. A study released last year by the Pew Hispanic Center found enrollment of Hispanic students aged 18 to 24 rose by 24 percent in a single year, a gain of such magnitude that I made some inquiries to double-check the numbers.

Yet, an attainment gap persists. Another recent report from Excelencia in Education found that only 21 percent of Hispanics have an associate degree or higher, compared to 57 percent of Asians, 44 percent of Whites, and 30 percent of Blacks.

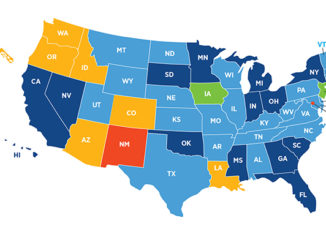

The report, Finding Your Workforce, listed dozens of colleges, mostly in Florida, Texas and California, that are generating the largest numbers of Hispanics with degrees.

Here, to explore the findings, is a guest post from Judith Maxwell Greig, president of Notre Dame de Namur University in Belmont, Calif.

A report issued March 9 by Excelencia in Education, a nonprofit research group, listed the top 25 institutions graduating Latinos and noted the critical challenges that face the American economy: Hispanics are the fastest-growing segment of the United States, yet they lag far behind other racial and ethnic groups in earning four-year degrees.

A report issued March 9 by Excelencia in Education, a nonprofit research group, listed the top 25 institutions graduating Latinos and noted the critical challenges that face the American economy: Hispanics are the fastest-growing segment of the United States, yet they lag far behind other racial and ethnic groups in earning four-year degrees.

It’s appropriate that Excelencia in Education’s report is called “Finding Your Workforce,” because demographic trends indicate Hispanics will comprise a large proportion of the U.S. workforce in decades to come. According to the 2010 census, the Hispanic population increased by 15.2 million between 2000 and 2010, accounting for more than half of the 27.3 million increase in total population. Yet only 13 percent of young Hispanics earn a bachelor’s degree, compared with 39 percent of whites and 21 percent of blacks, according to 2010 statistics compiled by researchers at the Education Trust. As a result, Hispanics are significantly less represented in professional jobs and more highly represented in construction, maintenance and service jobs.

As president of a Hispanic-serving institution, I believe this is one of the most crucial educational issues of our time. We’re in the midst of a huge demographic shift through which all educational leaders, whether in K-12 or higher education, need to learn to navigate. Here in San Mateo County, Calif., more than half of K-12 students are “minority,” and a third are Latino.

While there are many good, humanitarian arguments for why and how the public good will benefit from investing in educating Latino students, the hard, pragmatic truth is that going forward, the American economy will not prosper unless we do.

The Institute for Higher Education Policy noted in a report in early January that minority-serving institutions will be instrumental in achieving President Obama’s goal for America to be the leader in the proportion of adults with a degree in the world by 2020. That means we have some work to do.

One of the biggest obstacles to college completion for many minority students is that they are the first in their family to go to college, so they often lack the cultural knowledge about how to negotiate the system and succeed and earn a four-year degree. Many outside organizations, like the Peninsula College Fund, identify high-achieving, first-generation students and help them make their way through college. But colleges and universities, too, can help students over the hurdles that prevent them from completing a degree program by putting a few crucial support programs into place:

• Peer mentoring. Notre Dame de Namur University put a peer mentoring program in place two years ago, in which upper-class, first-generation students serve as role models and cheerleaders for their first-year peers. The mentors have lived through the same challenges their peers face and can offer practical assistance. While faculty mentoring is effective, we’ve found that our students often respond more positively to their peers, who are perceived as more approachable than faculty. For example, an upperclassman can talk to a freshman about the importance of going to class every day with completed homework as a success strategy in a way that’s perceived as a form of practical advice; by contrast, coming from faculty, the same advice might seem like a directive. This kind of mentoring is a key part of our “Gen 1” program, which has so far exceed even our loftiest expectations. First- to second-year retention of first-generation students participating with the peer mentors was 83 percent compared to 67 percent for non-first-generation students.

• Financial literacy training. The evidence we have points to finances as the biggest reason students of any race or ethnicity drop out of college. More colleges and universities have been adding financial literacy instruction to help students understand the economics of higher education. Outside organizations like American Student Assistance provide a forum for students to manage student loans and other financial decisions. Colleges and universities need to make this kind of training available for all students, with particular emphasis on first-generation students.

• One-on-one, executive-style student coaching. Notre Dame de Namur has begun working with InsideTrack, a national student coaching firm that conducts one-on-one sessions with students to help them set clear goals, make detailed plans to achieve them, and work through obstacles when they arise (such as financial issues, time management challenges and family issues). Colleges and universities that have implemented InsideTrack have seen, on average, a 15 percent increase in retention, according to an independent study funded by Stanford University last year. We’ve put this coaching service in place for all incoming students, with a particular emphasis on boosting completion rates for Hispanic students. California State University-Monterey Bay, also a Hispanic-serving institution, has seen generous increases in retention rates for Latino and first-generation students since providing InsideTrack for its students: Between 2006 and 2009, freshman retention for Latino students jumped from 65 percent to 78 percent; and for first-generation students (one of the most vulnerable groups) from 52 percent to 75 percent.

• Supplemental Instruction. Too often, underprepared students who lack only sufficient preparation for college level work are treated as though they lacked the necessary intellectual skills and capacity to succeed, and are put on a remedial educational path that leads nowhere. Universities today are finding far more success by offering Supplemental Instruction, which provides all students with structured, peer-assisted study sessions for holding discussions and comparing notes. These sessions are led by upperclassmen who act as “model students” for their peers.

Not all of these strategies will fit each university’s culture, but we’ve got enough arrows in our quiver to being taking aim at the looming retention and completion issues facing Hispanic and first-generation students. What we require most now is a national will to accomplish the goal.