by Garret M. Graff, POLITICO

To hear Congress tell it, there are hordes of hardened jihadist fighters waiting just over the Mexican border to launch suicide attacks on unsuspecting Americans. Texas Rep. Louis Gohmert has even warned of al Qaeda training camps in Mexico, run in conjunction with drug cartel members. Other Republican figures from New Hampshire Senate Candidate Scott Brown to Rep. Duncan Hunter have raised alarms about ISIL fighters infiltrating the southwestern United States, ready to do battle on America’s streets. “I think it’s a very real possibility that they may have already” crossed the border, Perry told a Washington audience this summer, as he sent Texas National Guard troops to boost border security.

Pennsylvania Republican Lou Barletta said in a hearing this fall, “I don’t know if we’re making the argument here of whether or not we should secure our southern border or not. That’s the feeling I’m getting. There’s been a lot of talk that whether or not any terrorists have crossed the border illegally.”

His GOP colleague, Rep. Jeff Duncan of South Carolina, angrily warned about ISIL coming north during a separate hearing this fall: “Wake up, America. With a porous southern border, we have no idea who’s in our country.”

The terrorism fear seems urgent. A Texas sheriff, hinting at nefarious doings, went on Fox News to report that there had been “Muslim clothing” and Qurans found on trails leading across the border.

And only last week, California Rep. Duncan Hunter reported, “At least 10 ISIS fighters have been caught coming across the border in Texas.”

The frenzied debate, though, has unwittingly exposed one of the strangest disconnects in post-9/11 American politics: While much of the political rhetoric around border security is focused on stopping terrorism, comparatively few of the U.S. border security resources are directed toward stopping terrorists from entering the United States. Instead, the billions of dollars of fencing, technology and personnel assigned since 9/11 to police the border has almost entirely been aimed at stopping illegal immigration along the southern border.

While politicians almost always complain about terrorism in the same breath that they call for more fences and Border Patrol agents along the Mexican border, it’s easy to tell that they’re not really concerned about terrorism. If terrorism—and not illegal immigration—were really their top concern, they wouldn’t be mentioning Mexico.

After all, there’s only one U.S. land border where federal agents have ever stopped jihadist terrorists.

Hint: It’s not the Mexican one.

Department of Homeland Security officials said Duncan Hunter’s claims were entirely wrong. There weren’t 10 ISIL fighters captured last week alone—there have been zero, ever. In fact, they’ve said that all of the Mexican border fears and claims have been unfounded. In hearing after hearing and statement after statement this fall, security officials have dismissed any suggestion that ISIL or any other jihadist group is trying to sneak across the Mexican border.

During a hearing last month, half a dozen Republican congressmen pushed administration officials, including DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson and National Counterterrorism Center Director Matt Olsen, about ISIL’s purported plans to sneak across the Mexican border.

Each demurred. Repeatedly.

Johnson said, “Congressman, we see no specific intelligence or evidence to suggest at present that ISIL is attempting to infiltrate this country through our southern border.”

Olsen said, “There have been a very small number of sympathizers with ISIL who have posted messages on social media about this, but we’ve seen nothing to indicate that there is any sort of operational effort or plot to infiltrate or move operatives from ISIL into the United States through the southern border.”

Johnson later in that same hearing: “We have no specific intelligence that members of ISIL are crossing into the United States on our southern border.”

Johnson later in that same hearing: “We have no specific intelligence that members of ISIL are crossing into the United States on our southern border.”

And Olsen again: “We’ve seen nothing to indicate any efforts to enter the United States through the southwest border by ISIL.”

Those and many other official protestations have not altered the political rhetoric at all, as protecting against phantom ISIL terrorists on the southern border has become one of the biggest Republican themes of the fall election season. And, in the latest twist on what’s been a regular bugaboo for months, New Hampshire Senate candidate Scott Brown last week argued that border security needed to be tightened to prevent people infected with Ebola from sneaking across unmonitored into the United States.

Yet, according to intelligence and homeland security officials, the talking points are all focused on the wrong border. While there is a good chance that ISIL fighters will try to enter the United States, there’s almost no chance that they’ll do it by sneaking across the Mexican border.

Instead, the United States has much more to fear from Canada.

Routes across the Mexican border come with two significant disadvantages for ISIL, al Qaeda, or any other would-be terrorists: First, the cross-border smuggling routes are controlled by Mexican criminal cartels, meaning that any inflitration attempt requires trusting and allying themselves with the cartels—an unlikely proposition for the naturally distrustful jihadist leaders, as well as for the cartels themselves. “Drug organizations have been very operational wary about entering into relationships that would facilitate terrorism,” explains John Cohen, who until June was DHS’s counterterrorism coordinator and is now a professor at Rutgers University. “They don’t want additional scrutiny from governmental agencies, because they understand that terrorism’s a whole other ballgame.”

Second, the demographics along the southern border, where there are few individuals with ties to countries like Yemen or Somalia, provide few resources on either side of the border for a local support network.

No official or former official I spoke with could even think of a significant al Qaeda or jihadist operation in Mexico, nor could any point to a sign that al Qaeda or other jihadist groups have attempted to gain a Mexican foothold. An analysis this summer by the intelligence firm Stratfor found that since the first jihadist-linked plot against the United States in 1990, the assassination of Jewish Defense League founder Meir Kahane in a Manhattan hotel, “None had any U.S.-Mexico border link.”

That’s not true up north. Canada has struggled publicly with its own jihadist terror plots. Just last year, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrested two men allegedly attempt to derail a train en route to New York City in what police said was an “al Qaeda-sponsored” plot. And in 2006, 18 men were arrested in an alleged wide-ranging plot to bomb and attack various Canadian targets—a plan that included an attempt to behead the Canadian prime minister.

That’s not true up north. Canada has struggled publicly with its own jihadist terror plots. Just last year, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrested two men allegedly attempt to derail a train en route to New York City in what police said was an “al Qaeda-sponsored” plot. And in 2006, 18 men were arrested in an alleged wide-ranging plot to bomb and attack various Canadian targets—a plan that included an attempt to behead the Canadian prime minister.

Quebec and Ontario, the two most populous Canadian provinces, boast large Arab and Middle Eastern immigrant communities, while U.S. border states like New York, Michigan and Minnesota all have similarly large immigrant populations. All have struggled to address domestic terrorism concerns and radicalized youth.

Neither the Border Patrol nor other federal law enforcement agencies have ever actually stopped an al Qaeda terrorist coming across the southern border—whereas on multiple occasions, federal agents have stopped terror suspects crossing in from Canada. In 1996, border agents three times stopped Gazi Ibrahim Abu Mezer entering the United States near Blaine, Washington, but after the third time, when Canada refused to take him back, he was released into the U.S. because the Border Patrol lacked sufficient detention facilities to hold him. In July of that year, he was shot in an NYPD raid while allegedly readying a suicide bomb to use on the New York City subway.

Later, in December 1999, an alert Customs agent, Diana Dean, stopped and searched Ahmed Ressam as he tried to enter Port Angeles, Washington, with the intention of blowing up LAX Airport, as part of what came to be known as the Millennium Plot. Other potential incidents remain classified. (It’s a myth, however, that some of the 9/11 hijackers entered the United States through Canada—albeit one that has been repeated by the likes of Hillary Clinton and John McCain.)

And once a possible terrorist crossed the border, what then? While there’s precious little evidence that ISIL or any other jihadist group has ready-made support networks in states like Texas or Arizona along the southern border, there’s been plenty of terror-linked activity along the U.S. northern border already this year.

Two Minnesota men have been killed fighting for ISIL in Syria and Iraq, both of them part of the huge 30,000-strong Somali-American population that lives around the Twin Cities and is centered in Minneapolis’s Cedar-Riverside neighborhood. News broke in September that a 19-year-old woman left her Minnesota home to help wounded ISIL fighters in Syria, bringing to what Somali community leaders say may be as many as 15 radicalized youth who have journeyed to the Middle East to join ISIL.

Radicalization is not a new problem for Minneapolis: The FBI and community leaders have publicly voiced concerns since 2007, when the first of what has turned out to be nearly two dozen local youths traveled from Minnesota to East Africa to link up with al-Shabaab, one of the jihadist groups affiliated with al Qaeda. Shirwa Ahmed, a former Minneapolis airport worker, killed himself in an October 2008 suicide bombing in Somalia—what U.S. officials say was the first-known suicide bombing by an American. Ahmed was also the first of what the FBI believes are at least six Minnesota men who have died fighting with al-Shabaab. (In fact, one of the only known terrorism connections to the southern border was when one of those Minnesota men, whom the FBI has charged is involved in recruiting efforts, actually left the U.S. for Somalia through the San Ysidro border crossing into Mexico.)

More recently, federal prosecutors have won convictions against eight Minneapolis men for facilitating terrorist recruitment and funding, and just indicted another Minnesota man last month for lying to federal agents about his contact with an alleged terrorist recruiter. Also in September, in one of the first U.S. cases dealing with ISIL, federal prosecutors indicted a man in Rochester, New York—across Lake Ontario from Toronto—for allegedly providing material support to ISIL.

U.S. officials aren’t taking the threat lightly. “These are communities that know the culture, know the language and have shown some sympathy to these causes,” an intelligence official told me.

On its website, the Border Patrol summarizes its mission as being the “the primary federal law enforcement organization responsible for preventing the entry of terrorists and terrorist weapons from entering the United States between official U.S. Customs and Border Protection ports of entry.”

Yet on a daily basis, nearly all of its effort goes towards policing illegal migration. The fact that border security actually has little to do with terrorism is evident from the way the Border Patrol allocates resources—devoting seemingly endless resources to the southern border, even as it leaves comparatively undefended and understaffed the only land border al Qaeda has ever actually used to sneak into the United States. While the southern border has miles of triple fencing, stadium lights and even surveillance blimps, vast stretches of the northern border are unpatrolled wilderness. “In many ways, in terms of the terrorist threat, it’s commonly accepted that the more significant threat” comes from the U.S.-Canada border, President Obama’s first CBP commissioner, Alan Bersin, told a 2011 Senate hearing.

A 2010 Congressional Research Service report echoed the obvious, writing that whereas the southern border’s primary goal was “containing unauthorized immigration,” the “main” concern on the northern border was its “vulnerability to terrorist infiltration.”

Altogether, the U.S.-Canada border is the longest international boundary in the world, stretching some 4,000 miles along the border of the lower 48 states, and another 1,500 miles along the Alaskan border. It has been historically undefended and little policed—a fact so widely accepted that it served as the comedic device behind actor John Candy’s final movie, “Canadian Bacon,” which satirized rising military tensions with our northern neighbor.

Despite the two public incidents with terrorists crossing the Canadian border in the 1990s, before Sept. 11, 2001, more than half of the official U.S. border crossings with Canada were left unguarded overnight and just 340 Border Patrol agents patrolled its entire length—responsible for roughly 50 miles apiece while on duty.

In the months immediately following 9/11, there was a brief period of strategic reassessment where hundreds of agents were shifted from the southern border to the northern border, but by the mid-2000s, as the Bush administration poured billions of dollars into new fencing and new agents, the longstanding imbalance had again taken hold. Today, out of about 22,000 Border Patrol agents nationwide, fewer than 3,000 cover the international boundary with Canada.

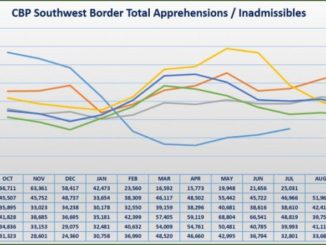

This year’s border crisis—which began with the spring’s huge influx of unaccompanied minors fleeing Central American violence and has continued with this fall’s heated election-year debate over potential ISIL infiltration from Mexico—has drawn renewed attention to the stalled battle within DHS to shift its border metrics from “quantity to quality.”

“South Texas has huge numbers, but the northern border has much better ‘quality.’ We don’t catch that many people sneaking across from Canada but those we do are much more interesting,” a senior CBP official told me this fall, requesting anonymity in order to discuss the administration’s border strategy. “Everyone knows the nexus of terrorism to Canada, but the administration doesn’t want to say that because it’d affect trade and commerce.”

The Obama administration has struggled throughout its tenure to figure out a proper metric for assessing border security and weighing “quality.” For many years, DHS relied upon a measure called “operational control,” based on the percentage of the border that was considered “secured.” It abandoned that metric in 2010 and told Congress that it would switch to something called the “Border Condition Index,” which more broadly measured such factors as economic growth, trade and commerce, crime rates in border cities and total apprehensions (as well as who, precisely, was apprehended). DHS spent three years working to develop such a measurement, then eventually abandoned the idea altogether under congressional pressure. It does not currently have a specific metric or estimate about the relative security of either the northern or southern borders.

The last publicly released number in 2010 showed the wide disparity between south and north. In that final year the Border Patrol released such statistics, the agency reported having “operational control” of 13 percent of the nation’s 8,607-mile border. Of those 1,107 miles of “secure” border, most fell on the politically fraught southern border, where both the Bush and the Obama administrations have dispatched thousands of new agents and built some 700 miles of fencing. The Border Patrol reported operational control of 873 miles of the 2,000-mile long southern border, as well as 165 miles along the coastal borders. What about the 4,000-mile long continental U.S. northern border? Just 69 miles.

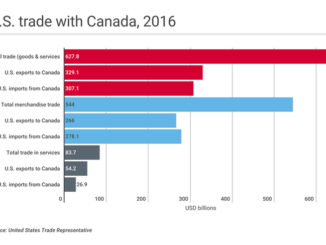

The close friendship and strong economic partnership with Canada makes an honest conversation about the northern border threat difficult. The United States and Canada have the world’s largest bilateral trade relationship, exchanging nearly half-a-trillion dollars worth of goods annually.

In 2009, then DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano got in political trouble when she said during an interview, “To the extent that terrorists have come into our country or suspected or known terrorists have entered our country across a border, it’s been across the Canadian border. There are real issues there.”

In follow-up comments, while stressing that Canada was a “close ally,” she added, “The fact of the matter is that Canada allows people into its country that we do not allow into ours.”

Napolitano’s public comments are echoed privately even today by other intelligence officials. Cooperation with Canadian authorities isn’t always as lockstep as one might assume. While Canada is a critical part of the so-called “Five Eyes” alliance, the five English-speaking countries that have tightly integrated intelligence and counterterrorism operations—Britain, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the United States—Canada maintains its own systems and assessments that differ from U.S. standards. For instance, just because an individual is on the U.S. “no-fly list” wouldn’t mean that same individual is prohibited from flying into Canada.

U.S. officials say that while they overall have an excellent relationship with Canadian security officials, there are always concerns about cross-border partnerships. “There’s a big effort in the homeland security community to increase intelligence sharing,” one senior intelligence official told me diplomatically this week. “Canada can be hesitant to share information about its own citizens,” another intelligence official said, adding that the United States similarly circumspect in discussing Americans with foreign intelligence agencies. U.S. intelligence agencies, moreover, can’t direct Canadian surveillance resources, meaning that individuals that concern U.S. officials don’t always receive the coverage they would prefer.

In the end, though, it seems unlikely ISIL or al Qaeda members would really need to sneak across either border. Historically, potential terrorists have done fine arriving in the United States like most other travelers: by purchasing a ticket on a commercial airliner. That’s how all the 9/11 hijackers got here, and how the 2010 “underwear bomber” arrived in Detroit. The trick is to find willing operatives who won’t trigger suspicion. As Cohen explains, “They’re not looking at smuggling people through human trafficking networks. They’re recruiting people from the West who would have an easier ability to enter the country legally.”

FBI director Jim Comey told “60 Minutes” this month that he estimates there are at least a dozen Americans fighting with ISIL in the Middle East—and they wouldn’t need to sneak back across any border to reenter the United States.

They’ve got valid U.S. passports.