When conservatives hark back to a golden age, they understandably think of the 1980s and the economic growth and Cold War victory that President Reagan unleashed. But there’s an argument to be made that the apogee of conservative social policy was actually in the 1990s, with tough-on-crime laws, which broke the back of a crack-fueled murder wave; welfare reform, which reined in government dependency; and education reform, which curbed monopoly power of the teachers’ unions in our big cities.

It’s no surprise that folks on the left deplore this trifecta today, as they did then. And there’s no shame in conservatives’ reappraising certain consequences of their ’90s agenda, such as mass incarceration. What’s worrying, though, is to see conservatives grow soft on what has arguably been the most successful and transformative part of the package: education reform, particularly the charter school movement. That’s one way to read the recent poll from Education Next, where I serve as an executive editor.

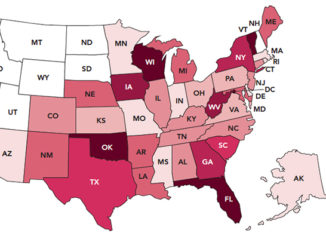

We found a 12-percentage-point drop in public support for charter schools from the spring of 2016 to the spring of 2017. What’s most surprising is that Republican and Republican-leaning respondents helped to drive this trend, with GOP support down 13 percentage points. Nor is this a one-year blip; roll back the tape to 2012 and Republican support for charter schools is down a whopping 22 points.

The puzzle is why. This is no idle question, as Republican support has been crucial to the growth and success of the charter movement over the past twenty-five years.

While the charter movement has historically received proud bipartisan backing in Washington—Presidents Clinton and Obama both strongly supported charter schools, as have Presidents Bush II and Trump—charters are almost entirely a GOP accomplishment at the state level, where charter policy is made. To be sure, some blue and purple states can count a handful of Democratic legislators and the occasional Democratic governor as proponents, but the charter movement has relied on strong Republican support to sustain it. If that support evaporates, the movement could hit a brick wall.

One would imagine then, that advocates of charter schools would be exquisitely attentive to the political math at the heart of their coalition: They typically need virtually every Republican vote, plus a handful of Democrats. Such attention would inexorably lead to an obsession with shoring up support on the right side of the aisle, correct?

Well, no. Instead, many leaders of the charter movement have spent the past decade displaying their progressive credentials and chasing after Democratic votes that almost never materialize. Thus, the case for charter schools today is almost always made in social-justice terms—promoting charters’ success in closing achievement gaps, boosting poor kids’ chances of upward mobility, and alleviating systemic inequities. That was certainly the approach taken by President Obama and his social-justice-warrior secretary of education, Arne Duncan.

Nothing wrong with that—up to a point. But it becomes self-defeating when it erodes support among conservatives and Republicans, and the polling suggests that many Republican voters may no longer be aware of charter schools’ conservative pedigree. Maybe they will come back to the fold if reminded.

That’s certainly one way to read another part of the Education Next poll. We did an experiment in which half of respondents were told that President Trump supports charters. Not surprisingly, this tanked Democratic enthusiasm while driving Republican support dramatically higher—15 points higher, to be exact, which erased the decline from 2016 and then some. It’s possible, then, that the charter movement has been a little too successful in branding charter schools as a liberal thing.

So how to keep conservatives in the charter fold other than by tying the issue to particular politicians, especially one as toxic as Trump? One approach might be to boost the number of conservative and Republican voters who send their children to charter schools, but this is problematic for two reasons. First, it would take decades to accomplish, since the overwhelming majority of charters today are in distressed urban neighborhoods. And second, though charters’ current locations are partly based on student need, they also reflect political compromises: In many states, suburban Republican lawmakers have been happy to support charters so long as they don’t threaten the traditional public schools in their own leafy districts. In the short term, at least, creating suburban charters could hurt the political coalition more than it helps.

A simpler, more direct way to boost conservative support is to remind people what made charter schools conservative in the first place. This means emphasizing personal freedom and parental choice—how charters liberate families from a system in which the government assigns you a public school, take it or leave it. Choice brings free-market dynamics into public education, using the magic of competition to lift all boats. And while some conservatives understandably would prefer private school choice, which allows a family to select a religious school, for example, instead of an independently run public school, charters are much more than a way station to vouchers. They have proven to be scalable and powerful, especially in cities.

But there’s another aspect of charter schools that gets very little attention these days, especially from the social-justice types: Most are non-union. In fact, in most districts, union representation is the most significant difference between charter schools and traditional public schools. It’s hugely important. It’s why charter schools can and do fire ineffective teachers, why they can turn on a dime when an instructional approach isn’t working, why they can spend their money on the classroom instead of the bureaucracy, and why they can put the needs of students first, every day, all day. Yet most charter supporters almost never talk about any of this.

We should. Fordham’s most recent study gives us one opportunity. It finds that teachers in traditional public schools are three times as likely to be “chronically absent” from school as charter teachers, meaning they are absent more than ten days per year. And why might that be? Because union contracts often allow district teachers to take more than ten days of sick or personal leave—on top of school holidays, summer vacation, and professional-development days. That’s two weeks out of the classroom in a typical forty-week school year, and studies show that students learn significantly less under substitute teachers. Yet unions have the gall to demand these policies, and elected school boards have the cowardice to agree to them.

Charter schools, meanwhile, can and do expect their teachers to show up for work except in urgent situations. In some of the best charter networks, chronic teacher absenteeism is virtually nonexistent. That’s because their teachers are fully committed to student success, understand that their colleagues might have to cover for them while they are gone, and know they will be held accountable if they don’t do their part. In other words, charter schools are like most of America, where employees are treated like responsible adults—and where they rise to that responsibility.

We should talk about this more.

There are other “conservative” aspects of charter schools worth crowing about as well. Many practice a no-nonsense approach to discipline, for example, in which students are expected to follow rules or face suspensions—commonsense practices that many public schools are nonetheless outlawing. Others provide a “classical” education, with a focus on the Great Books of Western civilization that you almost never find in traditional public schools. Yet others are serious and thoughtful about helping their students follow the “success sequence”—finishing high school, getting a job, and getting married before having children—which social scientists have shown is a nearly foolproof way to avoid poverty.

Yet some charter supporters on the left implore those of us on the right to downplay these aspects. That is a big mistake. If we charter advocates want to maintain conservative and Republican support for these life-changing schools, we need to remember who our friends are—and help them remember why they liked us in the first place.

Mike Petrilli is president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, and executive editor of Education Next.